A nation of tall cheese-eaters

- Published

The Dutch drink a lot of milk, eat a lot of cheese, and are now the tallest people in the world. Could there be a connection? The author of a new book on the Netherlands, Ben Coates, explains how the Dutch became not only voracious but also very discerning cheese eaters.

Earlier this year, a museum in Amsterdam was the scene of a terrible crime. Doing their rounds at the end of a busy day, curators were horrified to discover that one of their most prized exhibits - a small shiny object glittering with 220 diamonds - was missing. A security video showed two young men in baseball caps loitering near the display case, but the police had no other leads. The world's most expensive cheese slicer was gone.

In some countries, a theft from the national cheese museum might sound like the plot for an animated children's film. In the Netherlands, however, cheese is a serious business. For the Dutch, cheeses, milk, yoghurts and other dairy products are not only staple foods but national symbols, and the bedrock of a major export industry.

The Netherlands' love of all things dairy is largely a consequence of its unique geography. Four hundred years ago, much of the country lay under water, and much of the rest was swampy marshland. "The buttock of the world", was how one 17th-Century visitor described it, "full of veines and bloud, but no bones". Over the next few centuries though, the Dutch embarked on an extraordinary project to rebuild their country. Thousands of canals were dug, and bogs were drained by hundreds of water-pumping windmills.

Some of the new land was built on, but large areas were also allocated to help feed the growing population of cities like Amsterdam. Silty reclaimed soil proved perfect for growing rich, moist grass, and that grass in turn made perfect food for cows. Thousands of the creatures soon were grazing happily on reclaimed land. The country's most popular breed - the black and white Friesian - became world famous. At one point, a Friesian called Pauline Wayne even lived at the White House, providing fresh milk for President William Howard Taft and giving personal "interviews" to the Washington Post.

President Taft's cow, Pauline Wayne, on the lawn on of the State, War and Navy Building, 1909

In the Netherlands, milk became a popular drink at a time when clean water was in short supply. Any that wasn't drunk was churned into butter or cheeses, often named after the towns where they were traded, such as Gouda (pronounced, to the confusion of cheese-lovers worldwide, "How-da"). In a neat circularity, stacks of tough cow hides were even used as foundations for buildings in Amsterdam: the cows which grazed on reclaimed land providing the foundations for further reclamation. By the 20th Century, the Dutch had fallen head over heels in love with the cow.

Today, the country's affection for all things bovine continues. The Netherlands now has more than 1.6 million dairy cows - roughly as many as Belgium, Denmark and Sweden combined. (The UK has slightly more, but is roughly six times the size). Dutch cattle produce more than 12 million tonnes of milk each year and some 800,000 tonnes of cheese - more than twice as much as the UK, external.

Dairy producers often adorn their packaging with pictures of docile cows grazing amid buttercups, watched over by ruddy old farmers. In truth, although the Netherlands still has many small farms, the industry is now dominated by a few large dairies like Friesland Campina. Two small Dutch butter businesses, which merged and started making margarine, helped give rise to one of largest companies in the world - Unilever.

Cows get priority at this crossing in the town of Voorst

According to the dairy association ZuivelNL, nearly 18,000 Dutch dairy farms now support 60,000 jobs nationwide. Nearly €7bn (£5.1bn) of dairy products are exported each year, to countries as far away as China, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia. With the Dutch economy taking a battering in recent years, the humble dairy cow now finds itself shouldering an unlikely burden, as one of the big beasts keeping the Dutch economy off the ground.

Dutch dairy exports might be even larger were it not for the fact that the Dutch eat so much dairy themselves. To the Dutch, milk and cheese are staples, as essential a part of the weekly shop as rice is for a Chinese shopper or teabags are for an Englishman. It's said that about a sixth of the average Dutch food shopping bill goes on dairy products. In a typical year, the average Dutch person consumes more than 25% more milk-based products, external than their British, American or German counterparts.

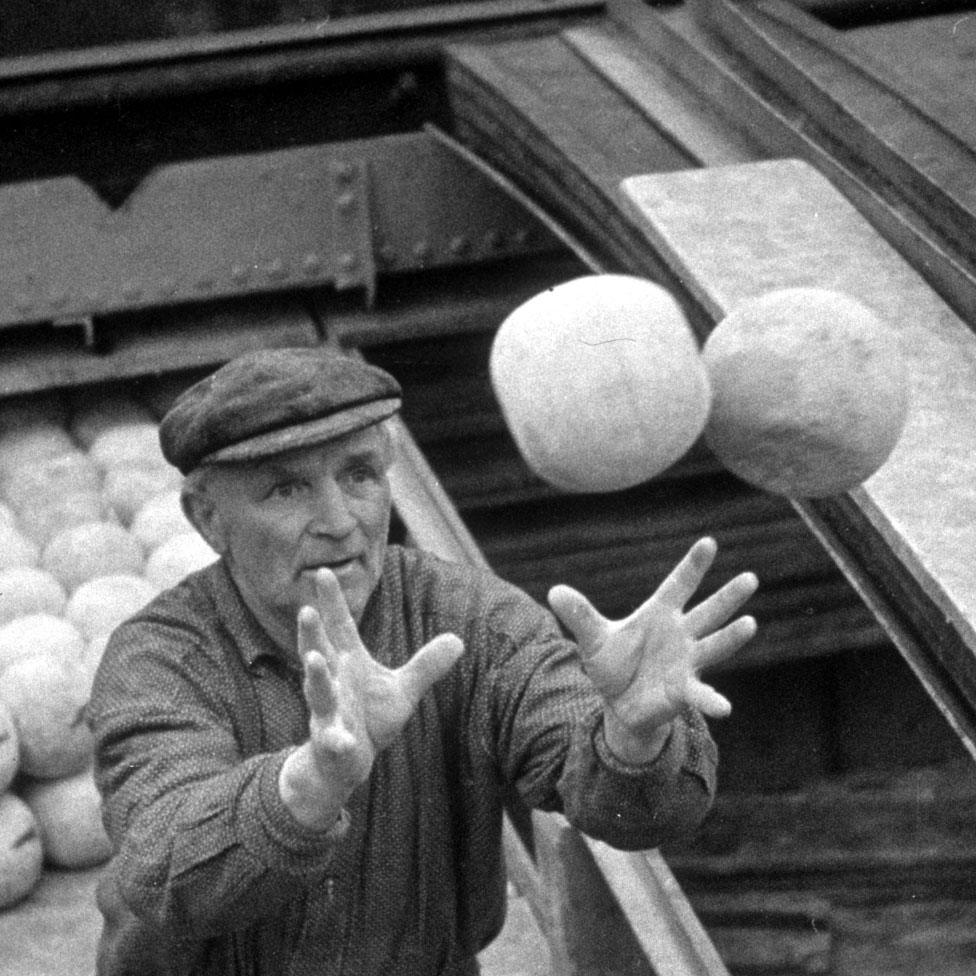

Dutch cuisine is not especially renowned internationally. Popular dishes tend to rely heavily on simple, earthy stodge such as cabbage and potatoes. Cheese, though, is a major exception, a foodstuff which can transform even the humblest Dutchman into a fussy gourmand. Markets throughout the Netherlands sell an astonishing range of different sizes, ages and flavours, from Maasdammer with its Swiss-style holes, to wagon wheel-sized Komijnekaas speckled with cumin seeds. Perhaps the most famous are the spherical Edams, coated in wax to help retain moisture and stacked in markets like cannonballs. In the 1840s, a Uruguayan battleship allegedly even used some Dutch cheeses as cannonballs - smashing the mainmast and ripping up the sails of an Argentine rival.

Edam cheese being loaded on to a barge in the late 1930s

In today's Netherlands, piles of cheese cubes make a popular bar snack, and nothing is more likely to get Dutch lips licking than a kaasplankje cheese platter. But cheese also makes a popular breakfast. Cereal isn't as popular as elsewhere in Europe, and morning trains are filled with commuters eating homemade brown-bread-and-cheese sandwiches for breakfast, often with milk or yoghurt on the side. Urban legend tells of a wealthy executive who complained to the national airline KLM about the food provided in business class. There was no need for all the fancy hot food and champagne, he said. A tasty cheese sandwich and a glass of milk would do just fine.

One might think that an all-dairy diet would bad for waistlines, but in fact the Dutch have grown mostly in the opposite direction. In the mid-1800s, the average Dutchman was about 5ft 4in tall (1m 63cm) - 3in (7.5cm) shorter than the average American. In 150-odd years of scoffing milk and cheese, however, the Dutch soared past the Americans and everyone else. These days, the average Dutchman is more than 6ft tall (1m 83cm), and the average Dutch woman about 5ft 7in (1m 70cm). The Dutch have gone from being among the shortest people in Europe to being the tallest in the world, external.

Cumin cheese, or Komijnekaas

Scientists continue to debate the causes of this growth spurt - improved nutrition, democratisation of wealth, genetic factors and the natural selection of tall men are all thought to play a role. One important clue is that the fact that growing tall appears to be contagious: immigrants who move to the Netherlands usually end up taller than people who remain in their home countries. So it's perfectly possible that the Dutch dairy addiction played a major role in turning one of the world's flattest places into a land of giants.

In recent years, dairy farmers throughout Europe have fallen on hard times. Exports to Russia, a sizeable market for Dutch cheese, collapsed last year during the conflict in Crimea. This year, the abolition of EU milk production quotas has forced milk prices down by some 20% in parts of the continent. For most Dutch, though, their love of lactose is as strong as ever. Milk remains one of the nation's favourite drinks, and cheese a national religion.

The diamond slicer that was stolen from the Cheese Museum has sadly never been found. In desperation, the company that made and owned it, Boska, has offered a reward, external which it hopes will attract the interest of its countrymen. Anyone who finds the slicer can claim the world's largest cheese fondue.

Ben Coates is the author of Why the Dutch Are Different: A Journey into the Hidden Heart of the Netherlands.

Is it just the cheese?

The height of Dutch people has intrigued scientists for many years - it's been suggested that the Dutch growth spurt could also be down to genetics, better medical care and natural selection, as Jane O'Brien found out on a trip to the Netherlands.

Why have the Dutch grown so tall?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.