Constance Leathart: The forgotten 'aviatrix' of WW2

- Published

Tracey Curtis-Taylor uncovers the forgotten story of Constance Leathart, one of a few women pilots who flew Spitfires during the Second World War.

Constance Leathart flew Spitfires in World War Two and was one of the first women with a pilot's licence - but her remarkable story has been largely forgotten, says Chris Jackson.

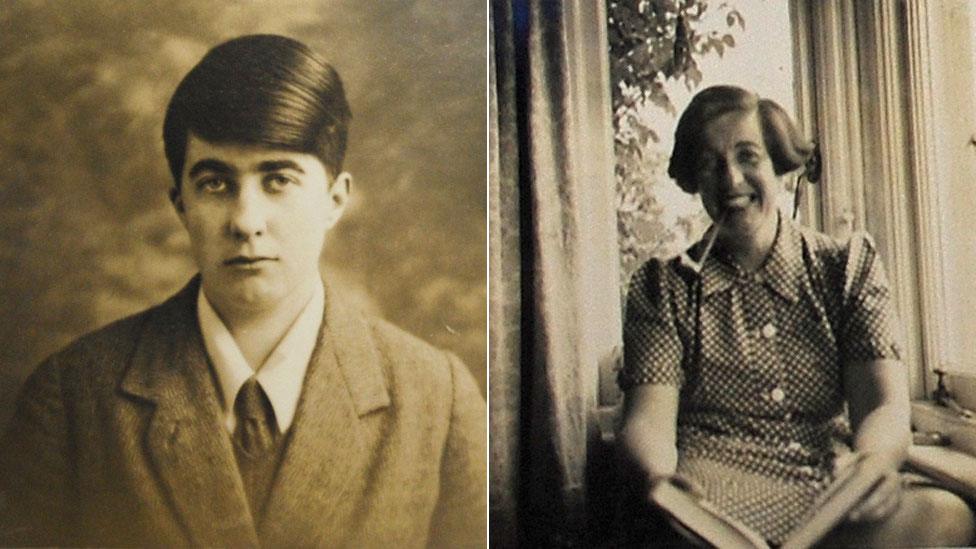

In 1925 a would-be pilot booked a flying lesson. The application to join Newcastle Aero club at Cramlington airfield was signed "CR Leathart". Only after she was accepted did anyone realise the first initial stood for Constance.

In her early 20s she hid behind those initials in order to break into the boys' club that was aviation in its early years.

She went on to become a hugely experienced pilot and flew fighters and bombers during WW2. In peacetime she flew alongside an elite band of socialite aviators and liked whisky, cigars and woodbines between flights.

But her flying career got off to a bumpy start. On her first solo landing she crashed Novocastria, the club's Gypsy Moth light aircraft, but emerged uninjured and undeterred.

In fact, very little could faze her. Aspiring pilots had to conduct a manoeuvre known as a height test but when her turn came one afternoon it suddenly became very dark.

On the ground, worried club members positioned their car headlights to guide her to the runway. Flight magazine records how, after executing a perfect landing, "Miss Leathart was quite surprised that anyone was perturbed about the matter. She certainly was not".

Novocastria, the club's Gypsy Moth, which Constance crashed

A few months later she became the first woman outside of London to be granted a pilot's licence. In 1927 there were only 20 British female flyers, or aviatrices, at all.

You couldn't afford to fly unless you had some money behind you. Leathart was born into a wealthy north-east of England family. The Leatharts had amassed their fortune as owners of lead works on Tyneside.

As an only daughter, she perhaps had something to prove. Family friend Dora Ions recalls how later in life she confided that her father had wanted a son. "She dressed more like a man. She told me herself that she did that for her father. She tried to please him."

She had a toolkit, knew how to use it and wasn't afraid to get her hands dirty. Together with lifelong friend Walter Runciman, later Viscount Runciman, she set up an aircraft repair business.

The pair would take part in air races at which both were successful. For the sheer pleasure of flying they embarked on grand European expeditions with other well-to-do aviators.

Constance even had a special locker cut into the fuselage of her trusty Comper Swift to accommodate the picnic hamper she rarely travelled without.

Yet amongst the rather glamorous winged socialites, Con, as her closest friends were allowed to call her, cut a rather solitary figure. She could look very smart with her short crop haircut, tie and jacket, but you'll not find many photos of her in feminine finery.

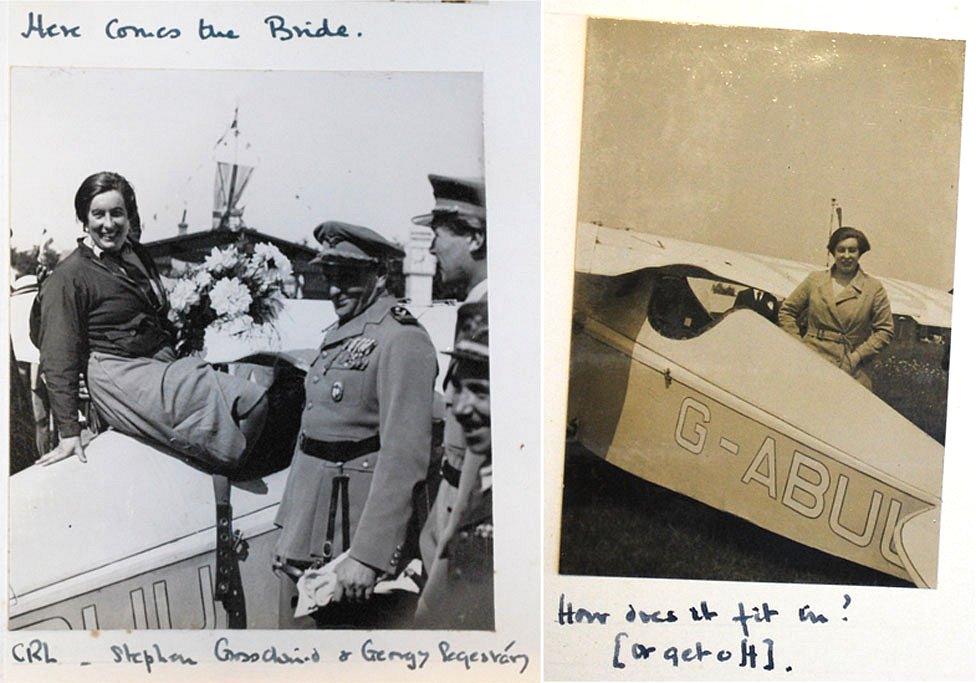

Her photo albums are testament to a life devoted to flying and are packed with images of aircraft both home and abroad. When naming those in the shot she identifies herself simply as "CRL" (the R stood for Ruth).

The pages also betray something of her outlook on life. In the margins she'd write self-deprecating captions referring to her physique and appearance.

Her 1945 snapshot album is subtitled "One Fat Cow". Next to an image of her stood by her plane, she scribbled "How does it fit in?" On a flight to Hungary, where women pilots were unheard of, she was presented with a huge bouquet of flowers. Her only comment, apparently brimming with irony: "here comes the bride".

Leathart never did marry. If there ever was a chance of romance you won't find any hint of it in those albums which, along with other personal items are now in the care of the Northumberland Archives.

It's a remarkable collection, not least because it contains a fantastic amount of detail about her service in WW2.

She was one of the first women to join the Air Transport Auxiliary. Its job was to ferry planes from factory to aerodromes across the UK to keep the RAF flying.

Any male pilots fit enough went into combat, so at first the delivery duties were given to World War One veterans. When they couldn't keep up with demand, the powers that-be were compelled to allow women in to the ATA.

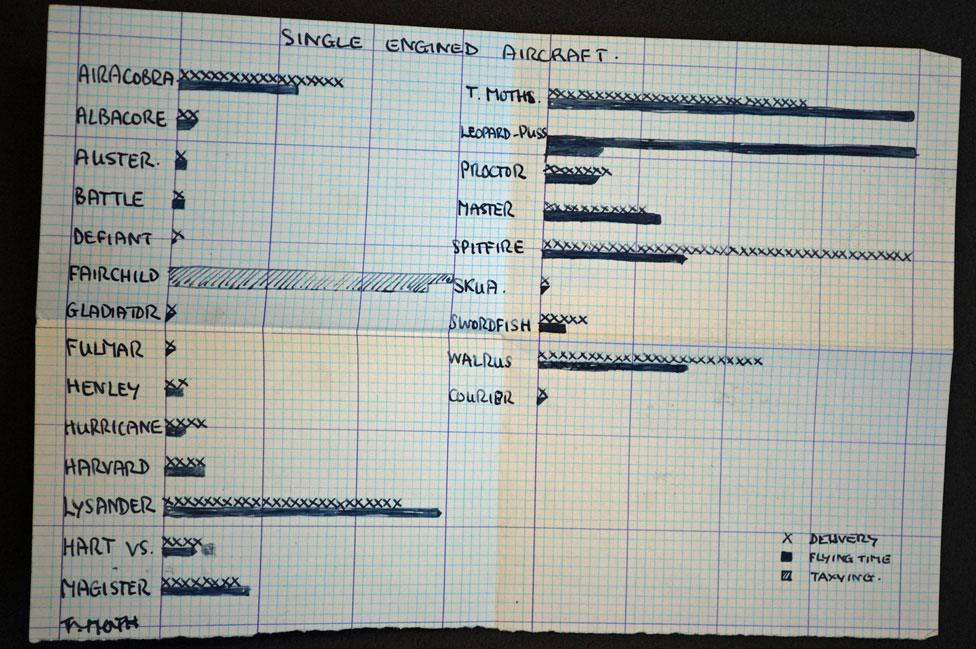

Constance kept a tally of all the aircraft she flew whilst with the ATA

Aviation historian Richard Poad says with more than 700 hours flying in 16 different types of aircraft, Constance had a remarkable amount of experience for a "new" recruit.

At first female ATA pilots were only given rather mundane flying tasks, but it wasn't long before they were let loose on fighters and bombers.

Pilots were instructed to keep under 250 miles an hour when delivering a Spitfire, says Poad, who helped establish the ATA museum at Maidenhead Heritage Centre. But he adds: "You tell that to a hot-blooded woman or man in a plane that will do 400. They weren't supposed to go low flying - they did. They weren't supposed to do stunts - they did."

Constance, left, with her fellow ATA women pilots

The press couldn't resist the story of women flying combat aircraft and some were photographed as pin ups which rather undermined the serious nature of their war effort work. You won't find Leathart in any of those newspaper shots. She didn't fit the stereotype.

One of the few surviving ATA women recalls her surprise on meeting Flight Captain Leathart - her rank was the ATA equivalent of squadron leader - who was giving her a lift to pick up a spitfire.

Molly Rose describes her senior officer as being "very short and extraordinarily square. I was amazed that she was tall enough or agile enough to cope with the flying".

Her ATA record states: "Leathart flies well and although rather lacking in polish she is perfectly safe."

Women at war

At its peak, more than 7 million British women were engaged in war work during the Second World War

180,300 worked in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and hundreds of thousands more in the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) and Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS)

But after the war the government encouraged a return to domesticity. By 1951 the number of women in work had almost returned to the pre-war level

It was dangerous work. The fighter planes they flew from the production lines were unarmed and without radio and they had to navigate by sight. The biggest enemy wasn't a Messerschmitt, but bad weather.

Amy Johnson - who had become a national hero with her solo flight to Australia - was a friend and contemporary of Constance in the ATA. Amy died in service when she crashed in the Thames estuary after going off course in bad visibility whilst delivering a plane.

Amy Johnson became friends with Constance

A little known fact is that women ATA pilots were, after some wrangling, paid the same as the men. At the war's end. however, women were expected to report back for duty at the kitchen sink.

But Constance felt the ravages of WW2 still needed her attention.

She went to the island of Icaria which, ravaged by Nazi occupation and civil war, had left its population on the brink of starvation. As a UN special representative she helped distribute food and medical supplies.

According to a story told years later, she arrived with supplies but the locals, fearing an attack, were at first hostile until in her no-nonsense style she explained she was there to help. The Northumberland Archives and librarians at the United Nations are unable to verify that account.

But a number of letters survive in which she pleads with her superiors for more assistance, especially for the children of the island.

Friends recall some vague mention of Constance being given a Greek Island by a "president".

In the archives there is indeed a presidential letter, effusive in its praise of a British heroine. Closer examination reveals "President" is the Greek title given to Icaria's civic leader. More of a mayor than the head of a sovereign nation.

There's no promise of an island in return for her good work but she was given an Award of Merit by the prestigious International Union of Child Welfare.

On her return to the UK, she gave up flying and retired to a Northumberland farm to enjoy the obscurity she craved. It was a frugal life caring for rescue donkeys.

Constance with her lifelong friend Walter Runciman and her rescued donkeys

Friends recount how an invitation to dinner might be beans on toast and sleeping over in a bedroom colder than the air outside.

If the living room fire needed energising a quick dousing of petrol seemed to do the trick and woe betides anyone she gave a lift to. Perhaps someone who was used to tearing around in a spitfire should never be trusted on the road.

In her will she asked to be buried in an unmarked grave. She might have vanished from this earth without a trace but Derek and Dora Ions who cared for her in later life had an inspired idea. Her friends agreed it would go some way to showing how much she was loved.

A stone that served as a step into an unheated swimming pool she used in all weathers was placed by her grave. Derek carved her initials.

It was a discreet marker to commemorate the person, but not her remarkable achievements.

More from the Magazine

Constance Leathart's story can be seen on Inside Out on BBC One, North East and Cumbria, at 7:30pm on 12 October and nationwide on the iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.