Sue Lloyd-Roberts: How did she do it?

- Published

BBC journalist Sue Lloyd-Roberts, who forged a career in secret filming in secretive states, has died of leukaemia at the age of 64. Her courage, compassion and commitment to expose injustice the world over was an irritation to human rights abusers, and an inspiration to many journalists, including me. I'll miss her as a loyal friend and colleague. And her brave journalism will be missed by many.

I always wondered : "How does Sue Lloyd-Roberts do it?"

How did she keep her nerve when she posed as a European gems importer and filmed with a hidden camera in Rangoon, under repressive military rule, in 2007?

How did she keep calm when she crossed army lines in 2011 with a fake Syrian identity card to become the first Western journalist to secretly film opposition protests at the very beginning of Syria's uprising?

Sue Lloyd-Roberts reporting undercover in Homs

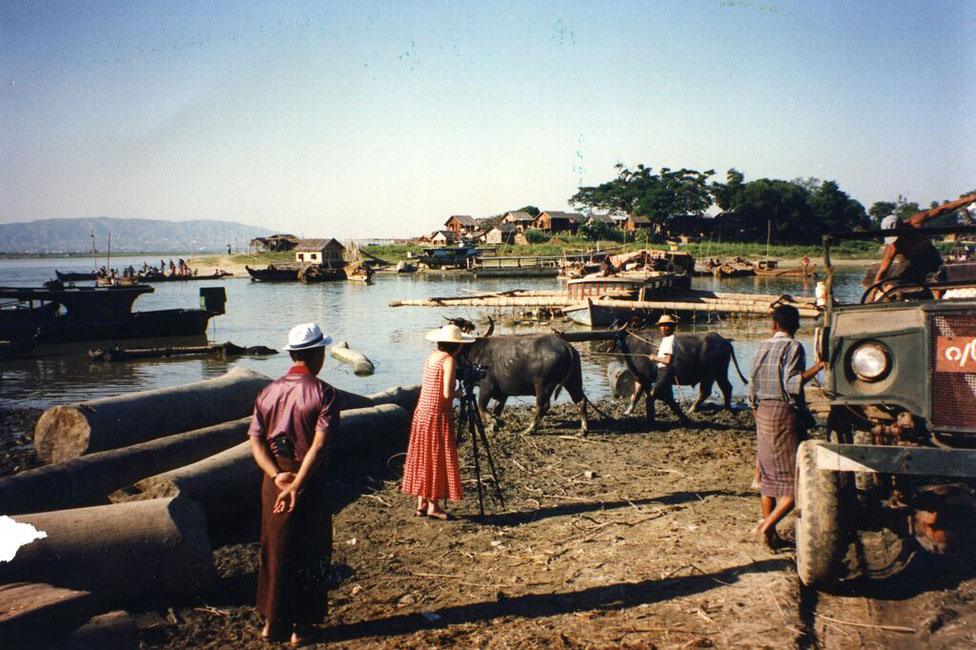

"My heart still quivers when I think of it," recalls BBC journalist Ian O'Reilly when he remembers their undercover filming inside military headquarters in Burma in 1997, a time when hardly any outsiders were able to enter the closed authoritarian state, much less penetrate the deepest darkest corridors of power.

When the sad news broke last night that a remarkable colleague had lost her long battle with leukaemia, I emailed Ian, a mutual friend who had worked with Sue on some of her most difficult and dangerous assignments for nearly 20 years.

"How did she keep her nerve?" I asked.

"Her nerve was her rage against the oppressor and the unjust and her absolute determination to expose and if possible humiliate the villain," he replied.

And that is the story of Sue Lloyd-Roberts' bold breathtaking journalism over more than 40 years.

Filming in Myanmar (Burma)

Only a week ago, at a cafe close to the BBC, Ian had relayed the wonderful news that Sue had just come out of her induced coma and had, almost miraculously, rallied again. A loud cheer had gone round our table.

About a year ago, at the same cafe, I had run into Sue who had cheerily shared her filming plans for 2015. I marvelled at her enduring commitment to keep telling the stories that had to be told, no matter how hard it was to tell them.

When her debilitating illness went into remission earlier this year, Sue just did what she always does: she prepared another film for the BBC's Newsnight programme, this time on the horrific plight of Iraq's Yazidi women who have been captured in the thousands and kept as sex slaves by the group that calls itself Islamic State.

Sue Lloyd-Roberts reports on Yazidi women captured by IS

Her piece to camera was achingly sad, yet so elegantly expressed.

"The three girls are very beautiful, with an aura of sadness about them despite their age, and a kind of deadness in their eyes which isn't surprising when they start telling you what happened to them," she said.

In many places for many years, people have been telling Sue Lloyd-Roberts what happened to them. Her list of films since she began work at the BBC in 1992 runs to 17 pages and is a roll call of the world's worst human rights abuses and abusers. And for 17 years before that, she did the same at Britain's Channel 4 and ITN.

Honour killings, female genital mutilation, trafficking of all kinds, the plight of indigenous peoples all came under her critical eye and compassionate heart.

Sue Lloyd-Robert tackles a Gambian preacher on genital mutilation

But more than that - she had a signature, a kind of designer label in the world of journalism. There was always something distinctive about her stories. Difficult to get. Often downright dangerous.

And she was often ahead of everyone else.

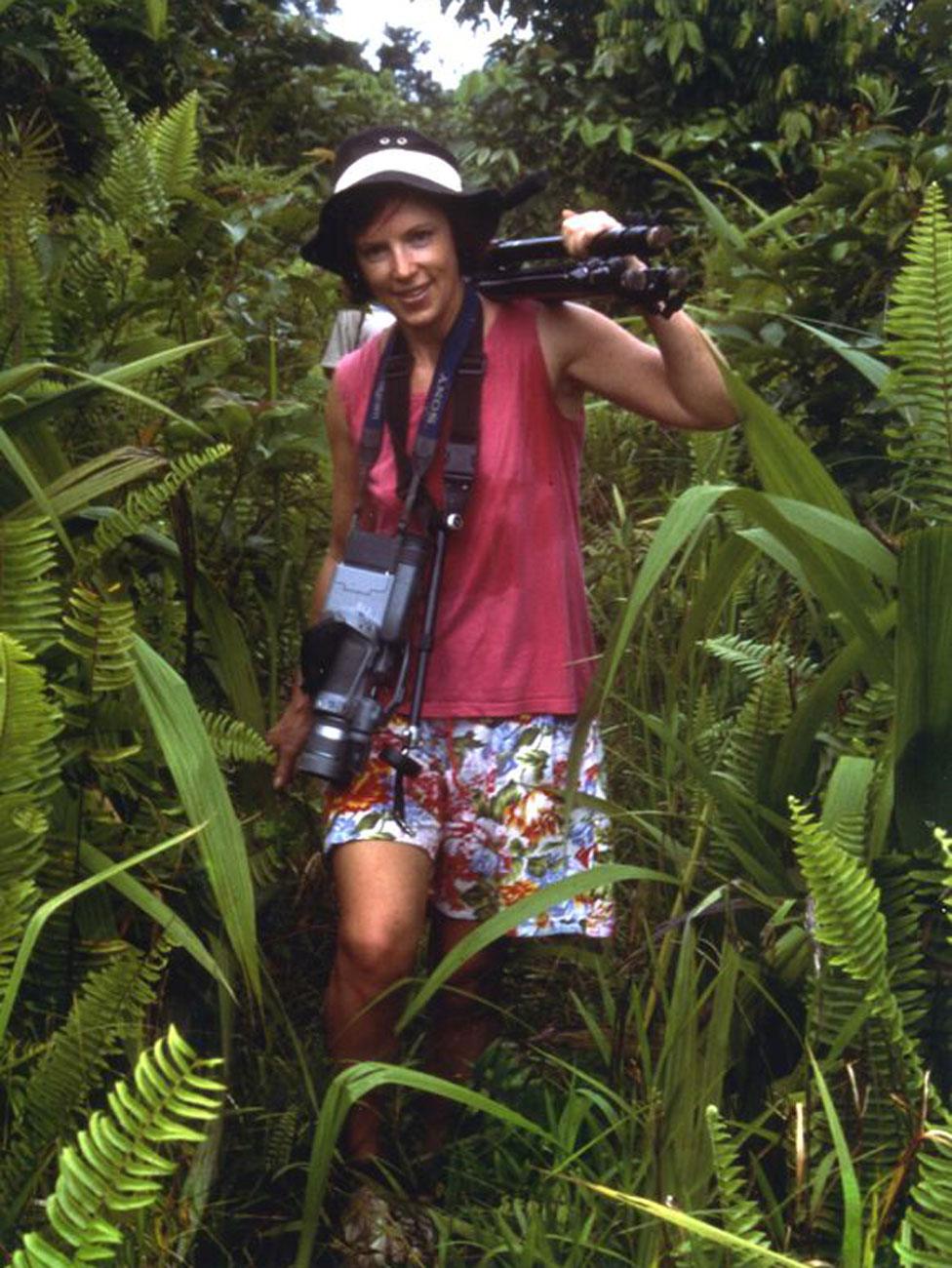

When a small affordable Hi8 video camera came on the market in the late 1980s she was one of the first investigative reporters to see its potential and power. Sue became one of the first "video journalists" long before the phrase was even coined.

"I owe so much to her," says Nancy Durham, who also started filming with a Hi8 camera in 1994 for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

"When I set off to gather stories in the Balkans everyone said, 'Oh you're like Sue Lloyd-Roberts,'" she recounts.

"Well of course I wanted to be but no-one could match Sue's ingenuity, courage, and fierce determination."

The other thing I often wondered about Sue was: "How did she get back in?" Not only did she manage to get into countries where journalists were barred, or tightly controlled, she would also keep going back to the same places for even more secret filming.

We now speak of being "googled" - suspicious officialdom can check the internet to see if you really are who you say you are. But Sue seemed to be able to travel the world on her Irish passport posing as a historian, an ornithologist, a tourist, a garment manufacturer - whatever it took to get her where she wanted to go.

Sue Lloyd-Roberts' Emmy-winning report from North Korea

Of course she upset people on the way. The BBC received endless complaints from officialdom, and sometimes even from other journalists, when Sue secretly came and went and then broadcast someone's secrets to the world.

"Oh my goodness, she got me into trouble," an Arab journalist remarked to me recently, about a trip where Sue managed to slip away from her government minder to film the story they didn't want filmed.

"She was so brave," reflected a young Syrian journalist who helped in her undercover work in her country.

Sue Lloyd-Roberts in Hanoi

But this toughest of journalists was also funny and feminine. On the road, her understated style was neatly pressed shirts with crisp collars. Outside work, I often complimented her on her lovely dresses and swirling skirts. And she was always unstintingly supportive, even in emails sent this year from her hospital bed where she became "an amateur expert" on haematology.

Leaving the BBC last night, I ran into colleagues and friends at Newsnight and we all paused, with the greatest of sadness and respect, to reflect on her extraordinary life and times.

"She was fearless, like a teenager," remarked studio director Meera Savosothy.

And then she recalled telling Sue that when she recently did her driving test, they were still using a video she had recorded years ago to show young drivers how to avoid making mistakes on the road.

"Are they still using that?" Sue had replied, with her distinctive throaty laugh. She had, for a time, forgotten that it even existed.

No-one will forget Sue's many films, and more than that, the road she took that helped us all gain a greater understanding of our far-from-perfect world - and who should be held accountable.

One of Sue Lloyd-Roberts' favourite films, about a US soldier who returned to Vietnam to find his son

Sue Lloyd-Roberts: Selected reports

The unopened 'Pleasure Hospital' of Bobo (March 2014)

Vietnam's illegal trade in rhino horn (February 2014)

Syrians accuse Greeks of pushing back migrant boats (June 2013)

Argentine grandmothers determined to find 'stolen' babies (April 2013)

Have India's poor become human guinea pigs? (November 2012)

Burma: The plight of Kachin state (April 2012)

Egypt's FGM continues, external (February 2012)

Saudi Arabia show of force stifles "day of rage" protests, external (March 2011)