The fall of Kids Company

- Published

The collapse of Kids Company continues to prompt many questions about the children's charity's management and finance. But what was behind its fall?

In February 1997, the Independent reported on a small charity in south London that was opening a new, permanent centre.

In what became a familiar fundraising refrain over the next 18 years, its charismatic leader said they believed they could spend "£500 a year to help a child, as opposed to the £2,500 that it costs clinics and agencies. To keep a young offender in an institution costs around £30,000 a year."

When it shut down in August 2015, Kids Company's website boasted of four centres, a therapy house and work in more than 40 schools in London. It claimed to work in six centres and six schools in Bristol. It was behind "a therapeutic performing arts programme for vulnerable and disadvantaged young people" in Liverpool.

It offered a range of services, from counselling and massage therapy through to intensive mentoring for young people living in the inner city. It worked, according to its literature, with children and young people. Despite the charity's child-centred name, some of its clients were over 30.

A woman is comforted outside the Kids Company premises, shortly after its closure in August 2015

Over the years, its mission did not creep so much as sprint. In addition to direct services, it ran campaigns. It funded scientific research, external and legal action against public policy. And Kids Company grew rapidly - from £2.4m of annual expenditure in 2004 to £23m in 2013.

And this phenomenal growth was underpinned by the personal attributes of its founder and chief executive, Camila Batmanghelidjh. The half-Iranian, half-Belgian woman was a fundraising force of nature.

The list of private beneficiaries tapped up by the self-dubbed "fat beggar" ranged from the leadership of elite banks through to established and experienced grant-makers.

The charity was supported to the very end by businessmen such as Richard Handover, a former chief executive of WHSmith who served as a trustee. A former minister said Prime Minister David Cameron was "mesmerised" by her.

"A fundraising force of nature": Batmanghelidjh at a charity event with Victoria Pendleton and Jamie Oliver in 2012

That is why, when Newsnight and BuzzFeed News revealed its impending sudden closure in August, it was such a shock. A temple of the establishment was falling. How, though, did it get to where it was?

From the beginning, Kids Company set out to be unusual. Its model parted with normal practices. When it closed, Batmanghelidjh said a major drain on Kids Company's finances was a core of 15,933 "clients". Each of them, she said, was assigned a "key worker". These key workers, often very young people themselves, would mentor, educate and assist clients.

The key workers, however, did not behave like social workers. Social workers retain a distance from the people they help to make sure their judgment is unclouded - they make sure they do not become "part of the family".

Staff members and children take part in a rally for Kids Company in Westminster earlier this year

But Kids Company key workers built unusually intimate relationships with clients. One former employee said: "There weren't that many boundaries in the sense that we were their parents, their surrogate parents. [We would] hug them, kiss them."

Defenders of the charity saw the social workers' professional distance as a problem. Social workers, they say, have become a cold emergency service - not a support service. You see a lot of references in Kids Company literature to the importance of love.

Kids Company set out to support young people that local authorities thought were not eligible for support. Their view was that the local authorities took on too few cases.

This approach was controversial in itself. But even more contentious was the financial support for clients. Lots received "allowances" of tens of pounds a week. Kids Company's defenders saw this as both helping poor young people with bills - and as part of an incentive structure to keep the young people engaged.

But former staff told us that some clients did little but collect allowances. This kind of generosity could be problematic - as could the charity's habit of giving extravagant gifts to children. It could undermine parents' authority. Furthermore, it could make vulnerable people into targets for exploitation and fuel bad habits.

Batmanghelidjh photographed in 2005 for a BBC documentary, Tough Love, about Kids Company

One former client told Radio 4's The Report that the day when allowances were paid was "weed heaven". We heard repeatedly how some clients at the Urban Academy would immediately spend their allowances on drugs (In reply, Batmanghelidjh said drug use was banned on the premises.)

The financial support also seemed to vary a great deal. After the charity closed, Newsnight and BuzzFeed News published excerpts from an interim investigation by PWC, the corporate services company, which found one client was receiving almost £1,000 a week in rent and allowances.

Given that the charity did deviate from normal processes so dramatically, you would expect funders to be more conscious of the charity's effectiveness, not less. But even simple questions went unanswered. We do not know how many clients it really had.

For example, take that claim that Kids Company had 15,933 clients requiring intensive help, each with a key worker to mentor them. As Genevieve Maitland Hudson, external, a former employee and a professional analyst of social policy, has written, this always seemed improbably high.

A 2009 visit by Prince Charles to Kids Company

If the caseload of 15,933 were shared equally among all of the 600 staff members, this would imply each Kids Company employee would have twice the caseload of the average children's social worker - a class of people that Batmanghelidjh always characterises as overstretched.

Furthermore, when we spent time watching their premises, we did not see the foot-traffic you would expect to meet their stated levels of activity. And when it collapsed, the charity handed over the names of just 1,900 young people to the local authorities.

The charity has said that the remaining names are in a database held by the Official Receiver, and that councils only sought a small number of names. The local authorities have flatly denied both claims.

If this were true, though, how could it go on for so long? There are few formal documents to help - few of its services were inspected by Ofsted, the education services regulator. The charity's own judgment was that the services it offered did not require it to register all its sites with Ofsted.

Local authorities were not involved, either - they did not habitually commission services from the charity, so social workers never put their heads around the door. There was no requirement that they be inspected.

And when Kids Company was challenged, its representatives had a familiar set of answers.

First, the measurement problem. Back in 2006, Batmanghelidjh wrote in her book Shattered Lives: "Often people ask what are our successes? What are our outcomes? I want to tell them the truth... The truth is that very disturbed children take a very long time to provide visible outcomes."

If pressed further, the charity would cite write-ups by academics which it had commissioned. These pieces of work were fine, as far as they went, but academics looked at specific parts of the charity's work and they failed to answer central issues - how many children did it help? How many did it keep out of prison? How many did it get into university? Was it good value for money?

When pressed harder, Kids Company would deploy lists of positive case studies. Or they would turn to a store of grim anecdotes. For example, when John Humphrys challenged Batmanghelidjh in August on Radio 4's Today programme, she started to speak of her recent role in preventing a suicide. "The police arrived and tried to grab him mid-air," she said.

Batmanghelidjh interviewed by John Humphrys on the Today programme, 6 August 2015

Finally, the charity would cite testimonies from local police forces, healthcare workers or politicians. A long dramatis personae of donors, journalists and MPs had their names cited repeatedly.

So how were they persuaded that this was a charity worth supporting? Part of the answer may be a pattern that has emerged from some former donors who turned into sceptics - when they turned up on the right day, they saw happy, jostling centres. But if they turned up on the wrong date, everything was very different.

Some people did start to reflect concerns. Journalist Harriet Sergeant wrote about the charity in her book Among the Hoods in 2012. She did not name it, but nor did she hide its identity. The Spectator raised some concerns early this year, external about what it actually did. But editors elsewhere seemed loath to run stories that were critical of the charity.

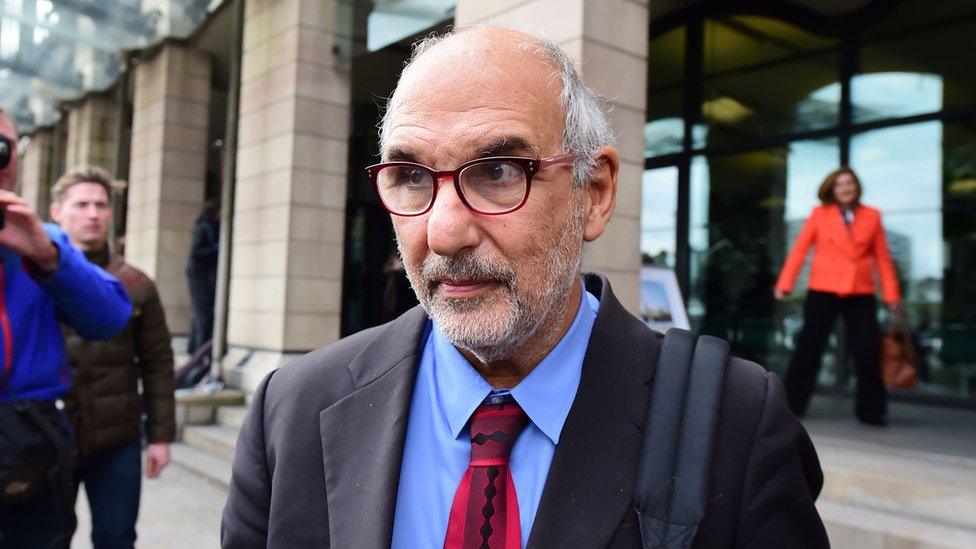

It helped that Kids Company was well connected. Its chair from 2003 until the end was Alan Yentob, the BBC's creative director. There are lots of archive photos of Batmanghelidjh in Technicolor gowns at society events - restaurant openings and art shows. The charity was embedded in that world - lots of staff members came from it too. Some celebrities even sought Batmanghelidjh's help as a therapist for their own children.

Kids Company was also garlanded at benefit events laid on by chic designers and won extensive support from figures ranging from JK Rowling to Coldplay. A good part of the charity's cash came, few strings attached, from outside the normal pool of experienced grant-makers.

And some of her fans were influential - Batmanghelidjh was a favourite of Prince Charles, for example. Some were powerful. The current prime minister became a major patron.

By the end, Kids Company's most generous backer had been the state. Kids Company went through £47m of public money - an astounding amount of cash for a charity that principally worked in south London.

So how did it win so much money from the government? The answer is what Batmanghelidjh referred to as the "bully strategy". In an internal document written in 2002, she said she hoped not to need to win funding by threatening ministers "with the outcomes of failing to deliver care to children".

This strategy, it turns out, worked on ministers from David Blunkett onwards. The National Audit Office last month wrote that the charity "followed a consistent pattern of behaviour that we observed in 2002, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2012 and 2015, each time Kids Company approached the end of a grant term... Kids Company [would] lobby the government for a new funding commitment".

It continued: "If officials resisted, the charity would write to ministers expressing fears of redundancies and the impact of service closures. Around the same time, Kids Company would express the same concerns in the media. Ministers [would] ask officials to review options for funding Kids Company. Officials would award grants to Kids Company."

Charity chairman and BBC executive Alan Yentob warned that closure of Kids Company could lead to arson, looting and rioting

In short - fund us or we will collapse, and the collapse will be horrific. Yentob sent a "risk assessment" to officials in June warning that a sudden closure of the charity would mean a "high risk of arson attacks on government buildings". It also warned of a high risk of "looting" and "rioting", and cautioned that the communities served by Kids Company could "descend into savagery".

Facing that kind of risk, and fearing an onslaught from Batmanghelidjh, Yentob and their friends, ministers feared to keep the chequebook shut.

After 2010, some ministers did want to hold back cash - notably Michael Gove and Tim Loughton at the Department of Education. It was Downing Street that pushed them to pay. Oliver Letwin, a Cabinet Office minister, and Steve Hilton, the prime minister's then-aide, pushed the spending through.

That is a role to which Letwin returned several times, although - as one ally of the prime minister puts it - Letwin is a "human shield" for the prime minister. He was, this minister says, only doing what Cameron wanted.

David Cameron with Camila Batmanghelidjh in 2010

Few hard questions were asked of Kids Company. But there were some. Civil servants were unhappy, for example. The Pilgrim Trust, a grant-making charity, wrote to the Charity Commission in 2002 with concerns about whether Kids Company was sufficiently competent.

In 2006, Kids Company's trustees were told by NPC, a charity that advises other charities, that its continued existence was, back then, "a triumph against the odds". It complained of "weak finances, conflicting information about numbers of users" and "the absence to date of any internal attempt even to track and record results".

The "bully strategy" only worked because the charity's financing was precarious. You need to be at risk of collapse to play the bully. But this was no ploy - Kids Company's philosophy guaranteed financial precariousness.

Kids Company did not have a definition of success when it would stop helping people, which meant that it built up a rump of clients who continued to get support. In Yentob's words: "Kids Company had a policy of not turning away or terminating care for young people if they still needed it."

In some cases, this went on until clients were well over the age of 30. As a result, the charity trapped itself on a funding treadmill, racing to raise enough money to keep up with its bills.

In 2014, the charity started to struggle to keep up. Donors had started to pull back.

Kids Company's now-closed Bristol base

Earlier this year, cash dried up - and so did the allowances. Windows sat broken, unrepaired. The crisis was so severe that Kids Company in effect cut a deal in March with the government to shut down some of its most distinctive services if things did not improve.

It secretly promised the government that it would draw up plans to close the Urban Academy in Southwark - its centre for over-16s. They pledged to work out how they might close down their Bristol operation too. These two proposals, if followed through, would dramatically change the nature of Kids Company - and even very senior staff were not told.

Kids Company was preparing contingency plans that would transform it into something smaller, more modest and more clearly focused on south London - and it got £4.3m of public money to do so.

The deal was signed on 31 March, and Kids Company was given two weeks to come up with a plan to explain how the closures might be achieved. Richard Heaton, then head of the Cabinet Office, told MPs the plan never arrived. But within two months, in a development that Heaton called "astonishing", the charity returned to government for more money.

Heaton used a little-known procedure - "seeking a ministerial direction" - to make public his view that ministers should not give it any more cash. He was, however, overruled. Matthew Hancock and Letwin, ministers at the Cabinet Office, ordered the payment of £3m - albeit with further conditions.

Camila Batmanghelidjh with Coldplay singer Chris Martin, a supporter of the charity

Deeper cuts were required of Kids Company. It agreed to appoint new trustees and a new chief executive. Batmanghelidjh had to step aside into a new job as "president". The body that spent £23m in 2013 would now spend under £10m a year.

Furthermore, the Cabinet Office learned of a "gobsmacking" report just three days before making a payment.

The document - an initial response to a set of allegations made by three former staff members - found that the charity had spent more than £50,000 on one individual, described as the child of an Iranian diplomat who was studying for a PhD. Two children of staff members, it said, benefited from more than £130,000 in client spending.

On the afternoon of 30 July, the charity received the £3m of Cabinet Office cash to pay for the restructuring. It was waiting for a further £3m of money from private donors to match it. It was this private money that was supposed to be used to cover running costs.

But Kids Company used the government cash to cover its overdue £880,000 pay bill for July - and that private donor money never came. Within hours of receiving the Cabinet Office cash, the police notified the charity of an investigation into allegations of unreported sexual assault.

So the trustees refused further donations and began shutting the charity down. A private donor says they were turned away. Almost immediately, the Cabinet Office started moving to recover their money (back in August, they expected to recover around £1.8m).

The police investigation was triggered by an interview Newsnight and Buzzfeed News did with a recent former staff member, external. She said she had been involved in a failure to notify the authorities of allegations of rape. She said she knew directly about a few complaints to staff from younger clients, aged 16 to 18.

They said they had been forced to have sex by older clients - and the police, she said, were not told. There was also an incident where a staff member was said to have been knocked unconscious by a client in an attack with snooker ball.

That member of staff was, however, also allegedly encouraged by Batmanghelidjh not to press charges. The young client said to have committed the attack is currently in prison for murder.

After taking advice, we notified the local authority about her testimony. Armed with her account, they found similar accounts - as did we - and New Scotland Yard opened a full investigation.

Batmanghelidjh denied having encouraged the staff member not to press charges, and the charity insisted it always notified the police of any criminal activity. The charity noted that it had serious safeguarding procedures.

At the moment, councils seem relaxed about the workload the closure has created for them - and the client base has been smaller than expected. But the story has not yet run its course.

The Insolvency Service is winding down the charity. The Metropolitan Police are still interviewing people, and still pursuing leads. The Charity Commission, the regulator for charities, has opened an investigation.

Kids Company closure timeline

26 June: Richard Heaton, permanent secretary for the Cabinet Office,, external writes to ministers raising concerns about Kids Company's request for a £3m government grant

29 June: Government ministers Oliver Letwin and Matthew Hancock write back, external, saying the grant should be given

2 July: A joint investigation by BBC's Newsnight and BuzzFeed reveals the charity has been told it will not get more public funding unless Batmanghelidjh, is replaced

3 July: Batmanghelidjh steps down, but denies the charity has been mismanaged

28 July: Batmanghelidjh writes to staff, apologising that they have not been paid yet, saying the charity is waiting for the £3m grant

30 July: She tells staff the grant has been received by the charity; the BBC learns an investigation into allegations involving Kids Company has been launched by the Metropolitan Police

5 August: The charity closes

6 August: Batmanghelidjh tells the BBC that Kids Company was subjected to a "trial by media"

7 August: Prime Minister David Cameron says the closure of the charity is "sad" but defends the £3m government grant

15 October: Batmanghelidjh and Yentob appear in front of the Commons Public Administration Committee (pictured)

29 October: A report by the National Audit Office reveals that the charity received at least £46m of public money despite repeated concerns about how it was run

Since the charity has closed, the Public Administration Committee has opened a review of the relationship between the charity and government. Yentob and Batmanghelidjh suffered a torrid morning of questioning from MPs, external - and opened themselves to further questions.

In that session, Yentob told MPs that "after Kids Company closed, a boy was murdered". But Bernard Jenkin, chairman of the committee, revealed that MPs had been told that violence had emerged after the charity shut because "desperate kids no longer had money to pay their drug pushers".

The Public Accounts Committee has been investigating too. They have had a go at senior civil servants.

Next week, though, Oliver Letwin, the minister with the longest period of responsibility for the funding of Kids Company, is being sent out to defend the government's decisions in front of MPs. Why did he sign off £7.3m of public spending since April?

The story of Kids Company is a tale of the establishment espousing a cause, and that charity's success in leveraging that acclaim into donations. It definitely did good work. Many of its staff were very committed. But while everyone was supporting it, no-one was checking whether the charity was a good investment.

More by Chris Cook

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.