Kids Company - do the sums add up?

- Published

- comments

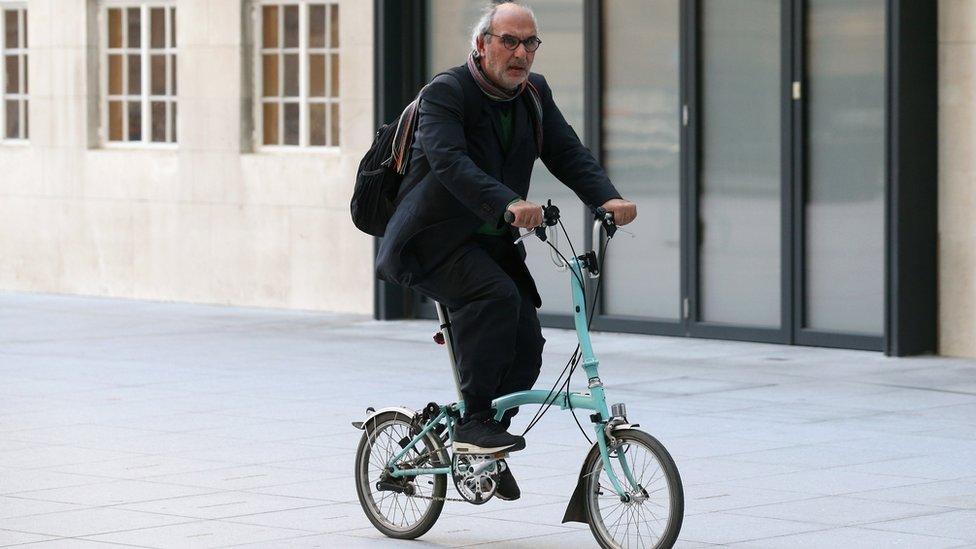

Alan Yentob has described suggestions of financial mismanagement as "complete rubbish"

At a select committee hearing late last week, Camila Batmanghelidjh and Alan Yentob presented their defence of their running of Kids Company, the youth work charity which collapsed in August just days after receiving a £3m grant from the Cabinet Office. But do the sums add up?

The former chief executive and former chairman of trustees had a bad day: they were unable to answer some big questions, many of which were raised by the BBC Newsnight and BuzzFeed News investigation into the charity.

For example, the charity had claimed to have 15,933 clients to whom it was giving intensive support, yet it handed over the details of fewer than 2,000 clients to local authorities. After hearing MPs probe Ms Batmanghelidjh's explanation for this gap, it seems very likely that this discrepancy is principally down to the fact that the charity was just smaller than had been claimed.

Second, Ms Batmanghelidjh claimed her staff had sought written authorisation to spend part of a £3m Cabinet Office grant on the charity's pay bill for July - which was not a permitted use for the grant. No email has emerged which supports this claim and the charity has not claimed that the civil service ever gave its consent. A charge of misusing a public grant seems to be sticking.

Third, the committee asked Mr Yentob about the warnings given by Kids Company to central government about the potential consequences of its closure: they warned of social disorder including a "high risk" of arson attacks on government buildings and "savagery" in parts of south London. MPs were incredulous that the document could have been meant seriously - and not as a threat.

They might have been interested in an internal strategy document written by Ms Batmanghelidjh in July 2002. She notes: "I hope we don't have to engage in the 'bully strategy' of extracting care. I would prefer not to threaten government with the outcomes of failing to deliver care to children." Ms Batmanghelidjh has declined to tell us whether the "savagery" letter was part of a "bully strategy".

Kids Company's collapse meant the closure of 11 centres in London and Bristol

Big questions on small reserves

A more complex issue, however, requires more unpacking. I have written before about the charity's finances: the committee sought to understand why the charity kept so little money as "free reserves". Charities like Kids Company, external hold money to cover an average of around five or six months of running costs. That means they can survive donor wobbles and - in extremis - can shut themselves down in an orderly fashion.

In each year until 2010, Kids Company's accounts stated their ambition to build their reserves. Their target was usually either three or six months of cash. But Kids Company never got near that. In their last accounts, for 2013, Kids Company had a mere £434,000. Three months of reserves would have been about £6m. Six months would have been about £12m.

As it happens, a reserve of more than £400,000 was good by Kids Company's standards. Since Mr Yentob took over as chairman, the charity had negative free reserves in 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006. It briefly had tiny positive reserves - £5,267 and £156,802 in 2007 and 2008 respectively - before drifting back into debt in 2009, 2010 and 2011.

Mr Yentob defended his record, telling the committee: "In 2012, there was a surplus, a reserve of £1.33m." Not quite. Yes, Kids Company ran a £1.33m surplus. But £1m was either already committed or legally restricted for use on specific projects. The charity only had around £270,000 of free reserves for use in emergencies.

It is important to note that a small reserve can often be justified. Mr Yentob argued that the charity had a big asset which, he implied, meant that the charity needed less in cash. That could be true: charities with easily disposable assets do, indeed, sometimes count them in their reserves. But I do not think that his argument quite works here.

Alan Yentob arrives to be quizzed by MPs

The Heart Yard

Mr Yentob was referring to a property in south London bought with donations from employees at Morgan Stanley in June 2012: the "Morgan Stanley Heart Yard" housed therapy facilities. In his testimony, Mr Yentob said it was worth £1.7m. That, he implied, permitted the charity to reduce the requirement to hold liquid reserves. I am not sure this works.

First, if the asset were easy to dispose of and it had a value of £1.7m that could be extracted in a hurry, then the charity would still be thinly provisioned. That would give the charity a £2.1m reserve in 2013 - only about a month's funding.

Second, the Land Registry records the sale price of 6-8 Hinton Road in mid-2012 as £650,000. The charity's accounts for 2013 put it at around £700,000, rising to as much as £1m after renovation. So a £1.7m valuation seems a little optimistic - even allowing for the madness of the London housing market.

Third, the Heart Yard was not an asset that could be dumped fast. It was a "functional asset". The charity needed it for services. So while it could be borrowed against, it could not be treated as an easily disposable asset. That was also the view of the charity's accountants; the 2013 accounts, external take the view that the value of the Heart Yard was not a resource that could be used to plug holes elsewhere.

Finally, Mr Yentob's chronology is odd. The charity only got the asset in mid-2012 - which coincided with an increase in Kids Company's reserves, not a fall. They certainly did not own the Heart Yard (or any significant assets) when they had no reserves at all.

So this argument just does not work. The committee heard no evidence that would lead you to doubt the conclusion drawn by Kirsty Weakley at Civil Society News, external a few weeks ago: "Instead of building reserves, Kids Company spent almost every penny it had... It is hard to avoid the conclusion that this was, at best, a naive and irresponsible attitude to financial management."

Chris Cook is policy editor for BBC Newsnight.