What makes a hero? Veterans share their stories

- Published

What makes a hero?

On Remembrance Day in the UK, and Veterans Day in the US, military veterans are thanked for their service and described as "heroes".

But for many this word "hero" feels uncomfortable, as the BBC's David Botti discovered in his web documentary What Makes A Hero?

Hundreds of veterans have responded to the film by sharing their stories and experiences. Below are just a few of the messages we have received so far.

David himself is a veteran and he will answer your questions about the film, external in a live Facebook Q&A on 11 November at 1600 GMT (1100 EST, 0800 PST).

Douglas Clifton, 66, Covington, Kentucky

Not everyone who puts on a uniform is a hero. I'm a combat veteran of the Vietnam War. Anytime anyone applies that label "hero" to me, it is awkward. I do feel uncomfortable.

I think it's often a way of some to assuage a feeling of guilt at not serving. In America only about 1% of the population is directly involved in our seemingly never-ending wars. And those not directly involved can lift themselves up by lifting the military onto some imaginary pedestal and heaping praise upon them.

No, not every soldier is a hero. And not every hero is a soldier. Currently, the term is much too overused. It diminishes those incredible moments when it is truly deserved.

During the 13 months I spent there, I flew on 151 combat missions, and was awarded the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters. Aircraft on which I flew routinely came under enemy fire - both anti-aircraft artillery and heavy machine gun. I lost several friends when one of my squadron's aircraft was shot down.

Upon my return, my family and some friends said they appreciated what I'd been through, but no one called me a hero. I didn't expect it; didn't want it. At the same time, no one called me a baby killer either, something that happened to far too many vets returning from that war.

It wasn't until the end of the first Gulf War that I began to feel some sense that we Vietnam vets were finally being recognised along with the veterans of the current war. And as so often happens, the pendulum swung too far in that new direction. Suddenly everyone was calling the collective "us" who were Vietnam veterans "heroes".

It has happened to me, usually around the Memorial Day and Veterans Day holidays. People I know would say it and I'd thank them. But it never felt right.

Yes, I'd served in combat. I had medals to prove it. But I wasn't a hero. I hadn't risked my life to save someone, or anything like that. I'd merely done my job. And I hadn't suffered doing it.

Not in the way I know one of my friends from my time overseas still suffers from having flown over 700 combat missions. He carries the emotional and psychological scars to this day. Compared to that, I count myself lucky. And I call HIM a hero!

Tossing out the label of "hero" has become an almost knee-jerk response. And in so doing, it has become all but meaningless. The same goes for the phrase, "Thank you for your service".

Or maybe it's worse than meaningless. It makes it too easy to glorify those doing the fighting. And if the soldiers - ALL the soldiers - represent some form of glory, doesn't that mean the fight itself is also worthy of glory?

If that's the case, who could possibly be against our wars? If you are, then you must be against our "heroes", right? That's far too dangerous a form of circular logic to buy into.

There are heroes in war. But war does not make heroes. The sooner we understand that, the sooner we, as a nation, will truly begin to honour our combat veterans. In the absence of that, calling them, calling us, all heroes is nothing but lip service.

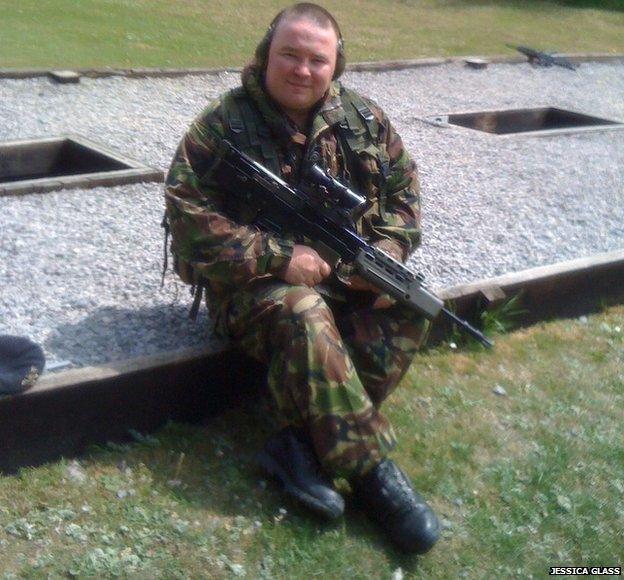

Jessica Glass, Tonbridge, Kent - speaking about her husband Carl

I consider my husband, Carl, to be a hero although he does not. He does however consider his colleagues to be heroes.

Whilst in Afghanistan, his actions saved the life of his 16 colleagues, for which he received praise (due to the nature of the operation he was never officially given a commendation).

He joined in 1998 at age 19 and served in the Royal Signals until 2012. He is now 36. He has struggled with PTSD [Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder] as a result of his service but is being supported by Combat Stress.

It's quite common for military to consider others heroes but themselves "just doing their job".

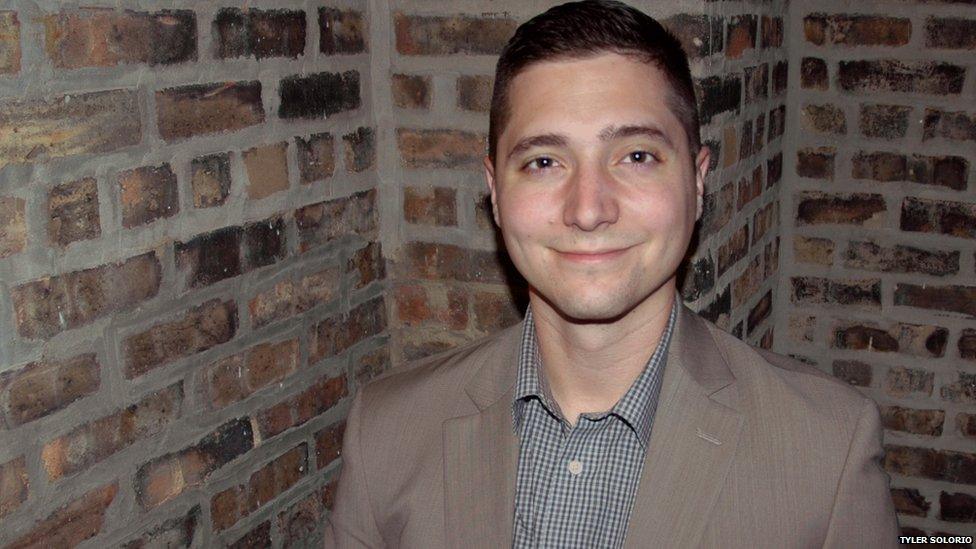

Tyler Solorio, 26, Chicago

I've been called a hero hundreds of times by people who don't know me. In any form, I hate it.

I don't know any soldier who enjoys it other than the soldiers that other soldiers don't want to be associated with it. It's egotistical, it has so many poor qualities. You don't trust a person who says they're a good person in the same sense you don't trust someone who embraces the hero title people bestow on them.

There are few heroes in the world in the same sense there are few among soldiers.

I was in the United States Army National Guard, where I did a year-long deployment to Afghanistan.

People say and ask things when it comes to soldiers that we constantly have issues with, it seems. Like when people ask if we've ever killed anyone, or thank us for our service.

Most of the soldiers I know try to avoid anything that would provoke a conversation because they just don't like what usually results, even if it is a person trying to be kind.

DeShauna Dunn, 30, Atlanta, Georgia

I'm an Air Force vet and I would not call myself a hero. I was just simply doing my job. A simple thank-you is enough.

I was in the Air Force from 2004 to 2006. Sadly, due to PTSD from a traumatic event I departed my military service early. I was an Operations Manager, which is a fancy way of saying a controller/dispatcher. Even with a short enlistment I had great times while in the Air Force.

As far as being called a hero, I think that really only happens during Veterans Day. I never really advertise the fact that I am a veteran and most people are surprised when they do find out. I will say that the American people are very quick to say thank you once they find out. I always appreciate it

Sometimes I feel that I am not deserving of the thank-you because I was not able to finish out my enlistment. However, I appreciate it nonetheless.

Austin Fish

I served in the US Marine Corps from 2008-12. But I was never deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan.

Being a veteran who didn't get deployed to those combat zones makes it pretty tough to hear these statements you express in the video. Most people ask right away did you kill anyone or how many people have you killed. I hate talking about or being asked about my service. I am not ashamed of my service, I am proud to be a US Marine and will always be proud.

I worked in the air wing with the Marine Corps and had to deal with a different type of combat that I call the combat of suicide. The reason I say that is because there was an enormous amount of suicides in my first unit in Beaufort South Carolina. We had 17 suicides just from the first eight months of my service. You can imagine how many more I had to deal with throughout my entire enlistment.

What hurts the most is that when I do speak of this to civilians, or ask if they have any idea about the suicide rate with active duty military or veterans, they normally have no idea. So it really makes me not want to speak about my service or be asked about it.

Then, when they tell me I am a hero or thank me for my service, I kind of lose my mind.

Reginald Davenport, 44, Chicago

I am a veteran myself (24 years in the US Air Force) and I don't mind people calling me a hero, or people thanking me for my service. But I do have some insight on why some may not feel comfortable with praise.

One aspect is the psychological damage that had already been done to those veterans of the earlier wars of WW2, Vietnam and Korea. They did not receive the gracious welcome back home that the younger veterans are currently receiving. In many instances a certain bitterness may build up and only over the course of time may those walls come down.

About a year or so ago I attended a college basketball game for which I received free tickets due to my status as a veteran. All veterans were invited on the floor before the game for the national anthem - I saw a couple of Vietnam veterans, and that put a lump in my throat.

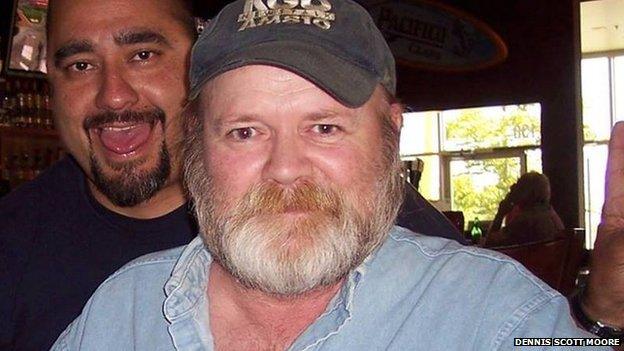

Dennis Scott Moore, 60, Sparks, Nevada

I did a couple of years in the Marines back in the mid-1970s and spent all of my time stationed at either Camp Pendleton, CA. or Kaneohe Bay on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. Lots of partying but nothing 'heroic' on my part.

On the other hand, about seven months ago, I couldn't get my truck to start (in a parking lot here in Reno, Nevada). I went back into the casino to see if I could use a phone to call for a tow truck, or get a "jump". The woman at the machine next to mine, overheard me explaining my dilemma to the cocktail waitress and called her son on her cell phone (a mechanic who happened to be at the other end of the building).

Not only did this guy check my engine (alternator or battery problems?) diagnose the problem and give me a jump, but he followed me to a nearby auto parts store, explained exactly what was wrong (the battery) and replaced it for me right there in the store's parking lot. He spent at least an hour helping me out and probably saved me a few hundred dollars in the process.

On that particular day (in my book) the dude was a HERO and an angel. He didn't ask for anything in return. I guess "heroes" come in many forms, depending upon the circumstance.

Veterans on Facebook respond to What Makes A Hero:

If people really want to thank a veteran, go down to the VA and volunteer. Thanking me for my service is about as useful as saying sorry for your loss when someone dies. Plus what are people thanking me for? I participated in an illegal war in Iraq that completely destabilised the region and did absolutely nothing for the American or British people. (William Kelly)

As a combat veteran, I feel that the overuse of the word hero has diminished the gravitas for when it's actually warranted. True "heroic" soldiers don't seek the glory of such fandom. We signed up to do a job. Did the job and that's it. I'd say if someone really wants to thank a veteran, if they know one, invite them over to hang out or go out for a beer. Don't thank them, just genuinely spend time with them. It's hard enough adjusting back to civilisation. Even if no words are spoken the whole time, just being there for a veteran is the greatest way to pay respect. That, and voting. (Andrew Gieseke)

I'm a Vietnam veteran. There were many heroes in the field of battle. Some survived, some didn't. When we returned home we were scorned. Now, no matter what you did in any conflict since the beginning of the war in Afghanistan and Iraq, upon your return home you are deemed a hero. I detest this and think that it is a jingoistic, nationalistic ploy to cover the terrible decisions US politicians made in declaring these wars. (Terry Long)

Just call us veterans and refer to us as men and women who served. My husband and I both served and we're not comfortable with the term hero either. We're proud of our service. I served one tour in Iraq and my husband served two or three tours in Iraq, one tour in Afghanistan, and is still serving on active duty. We're just one of many veterans who are proud but humble. Plus, after working in casualty and mortuary affairs as a civilian, and after taking part in arranging many active duty funerals and flights to send our deceased service members home, I feel that they're the true heroes. Because although we all put our lives on the line and sacrificed our family time, we got to come home alive while those men and women didn't. (Sharein N Jose)

None of us did it for the glory or respect of others. We did it for the life experience of being among the great Americans doing what Americans do for their country. We did it for us and it made us better human beings. Many would do it again if they were needed and were able to contribute. I never accept thanks for my service. After all is said and done. I got to be an American because of someone else's sacrifice and it is still the greatest community of heroes that the world has ever known. I am grateful for all I've been given just for being born here and I love the United States and all of my brethren who pledge allegiance. When you sign the enlistment document, you sign an open death warrant that can be served at any time during the six years. That's the ultimate benefit. If you haven't signed the paper, taken the oath, felt that obligation and pride, you'll never know what you're talking about. Just pledge allegiance and help where you can. (Thomas F McCoy)

Heroes are rare. Doing my job didn't make me a hero. What does upset me is when yahoo 'Mericans equate body count to heroism. That's disgusting. I also have come to dislike the phrase, "Thank you for your service." It's become an empty term that reminds me of how the nation turned its back on its returning veterans just like after Vietnam. People think they can say that and then pat themselves on the back like they did something. I prefer, "I appreciate what you've done." And, then, maybe ask what the person did over there. Actually try and act like you care. (Jeff Scott)

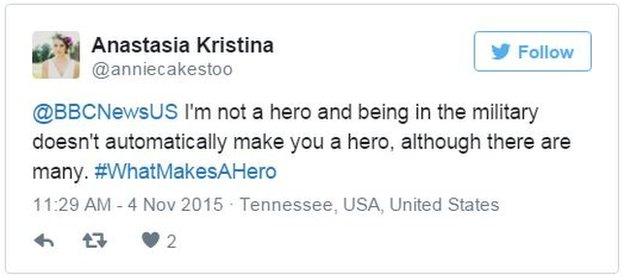

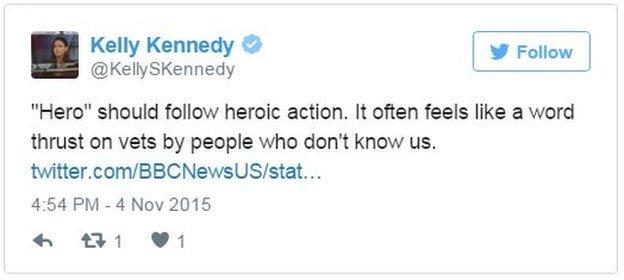

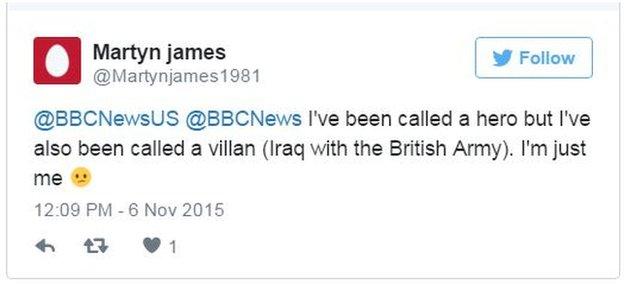

Tweets from veterans:

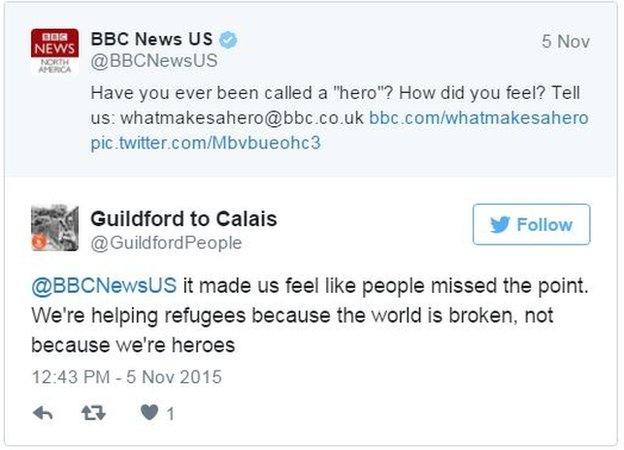

Reaction from non-veterans:

I think anyone that puts their neck on the line to defend or help people in turbulent areas of the planet are heroic - that doesn't just mean military. Perhaps Remembrance Day needs to commemorate other brave, selfless folk as well such as volunteer nurses fighting Ebola? (Magnus Johnson)

My colleagues think I'm a hero as I've survived cancer. I don't think I'm a hero, that's for people who save lives and things like that. (Debbie Smith)

I have been called a hero. I do not view myself as such. I did what I thought needed to be done at the time to help out in a bad situation. Others view that as heroic because it was not what they would have done, or perhaps not what they could have done. Additionally the word "hero" has connotations of superiority, ubermensch, of being above or better than the situation that is used to define them. "Heroes" remain fixed and constant, unaffected by what they endure and witness. I am more comfortable with being described as and thinking of myself as a survivor. I was impacted by the event and it has altered both my perception of life as well as how I choose to live my life. I think most people who are called heroes are actually survivors whose individual and/or group integrity and sense of purpose helped sustain them through a bad or extremely difficult time. (Christopher P Gehringer)

Yes I've been called a hero. And NO I did not feel that way. What makes a hero is a person who just does what they need to do when they need to do it instead of running the other way. They are the ones running toward the gunshots, the fire, the car crash instead of running away, or grabbing their cell phone and taking pictures. It isn't much. I simply pulled a guy from a wreck and did CPR until the ambulance got there. I just did what you do when someone is hurt and doesn't have a heartbeat. (Phil Harrison)

My friend hates this. He enlisted in 2002, intending to serve overseas in combat. Somehow, fortunately for his life but not so much his ambitions and intentions, he never saw combat. After training, he was in Okinawa, then a variety of other places, but he never made it into combat and was honourably discharged after serving his time. Anytime he goes anywhere with his family, they bring up the fact that he is a Marine to waiters and the powers-that-be to get discounts. People hear that he was in the Marines and thank him for his service and have used terms like "American hero" and he doesn't feel it's deserved. In fact, it makes him feel guilty because he never saw combat, but many of his friends from training did and were maimed or killed. Kind of a version of survivor guilt/imposter syndrome, I guess. (Heather Thein)

We need to understand that every country has men and women who choose to enter military life. Thank God for them and their decisions - which are not taken lightly! Think about this… if these people did not choose, forced conscription and national service would be inevitable since all countries need defence just in case! I believe they are all heroes, some more than others but still all heroes! It will be great to understand more and it is sheer stupidity to call armed forces assassins. They don't earn enough to qualify as assassins and yes they do follow orders, that is discipline and respect, something half the youth in the UK could do with learning! Better stop before I really lose my rag! (giglio_associates_ltd)

And finally... a poem

My Longest Day:

Do not call me hero,

When you see the medals that I wear,

Medals maketh not the hero,

They just prove that I was there.

Do not call me hero,

Now that I am old and grey,

I left a lad, returned a man,

They stole my youth that day.

Do not call me hero,

When we ran the wall of hail,

The blood, the fears, the cries, the tears

We left them where they fell.

Do not call me hero,

Each night I stop and pray,

For all the friends I knew and lost,

I survived my longest day.

Do not call me hero,

In the years that pass,

For all the real true heroes,

Have crosses, lined up on the grass.

By Rob Aitchison (submitted by Dave Quinn)

Compiled by James Morgan.

- Published2 November 2015

- Published2 November 2015

- Published2 November 2015

- Published2 November 2015

- Published2 November 2015