A legacy of fry-ups and red postboxes

- Published

The Queen has spent the past few days in Malta, where she opened a summit for the leaders of Commonwealth nations. She has soft spot for the place where she lived in the 1950s, when it was a colony. Although Malta is now an independent country the British legacy is still visible, writes Juliet Rix.

"Why are you looking at my house?" demands a not-particularly-friendly, grey-haired lady leaning out of an upper-floor window of the once-elegant Villa Guardamangia.

It's a crumbling, creamy limestone building, its green-painted woodwork peeling. What, I wonder, would she make of it if the Queen came tapping at the traditional dolphin door knocker asking to look at her old home?

The Queen, then still Princess Elizabeth and newly married to the Duke of Edinburgh, lived here in a quiet suburb of Malta's capital Valletta. Her husband was posted here with the Royal Navy and she is said to have been extremely happy living as an ordinary - well, relatively ordinary - officer's wife, shopping, socialising and driving herself around this Mediterranean island in an open-topped MG.

The Queens's former home, Villa Guardamangia

The Queen's continuing affection for Malta is very much reciprocated, at least by older Maltese. They associate her with the best of British Malta mentioning politeness to the solidarity of the war years.

"The most important British legacy is doing things properly," a senior Maltese journalist tells me, as we sit over coffee in the heart of the capital, under the stony stare of Queen Victoria. I ask what he means. "Good manners and low levels of serious corruption," he says. An antidote to the more typically Mediterranean, "laid-back, anything goes, approach".

It is certainly true that despite very close historic ties to Sicily, Malta has none of the problems with the Mafia that so hobble its nearest neighbour, and its economy is doing very much better than Italy's - perhaps, in part, due to the undoubted advantage in this globalised world of everyone speaking English.

Malta's civil service and its politics are still modelled on the British system. Indeed, some Maltese blame Britain for their adversarial nature and even accuse the UK of having fostered a policy of divide and rule. In my experience though, the Maltese are perfectly capable of being passionately confrontational with each other without any help from the British.

The then Princess Elizabeth, and the Duke of Edinburgh, in 1949 with Valletta in the background

An accusation with more glue perhaps, is that Britain bears some responsibility for Malta sharing its top spot in the European obesity league. Most of Britain's culinary legacy has long gone as Malta has returned to its healthier, tastier Mediterranean diet, but, insists a friend "the problem is the frying - and the popularity of the full English breakfast".

There are more obvious remnants of British rule of course: red postboxes and phone boxes (incongruous against baroque limestone facades that glow in the Mediterranean light), marching bands (one in every parish!), polo still played at the Marsa Sports Club, and panto - which, to the disgust of the artistic director of Valletta's main theatre, is hugely popular with the Maltese.

There is British architecture too: 19th Century forts, neoclassical law courts, dockyards, and barracks including the one inside Malta's oldest fortress, Fort St Angelo which the Commonwealth dignitaries were due to visit.

St Angelo has stood firm on the banks of the Grand Harbour for at least 800 years. It was the first base of the Knights of Malta and, for over a century, the headquarters of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, which is how Prince Philip will undoubtedly remember it. A just-completed 15m euro project has seen it beautifully restored and almost ready to open to the public.

This is just one of many heritage projects currently underway. Malta, in fact, seems in the grip of renovation fever. Bastions, palazzi, fortresses, squares and citadels are all being painstakingly restored.

And no period distinctions are made. British monuments are as carefully cared for as any other. There isn't any serious nostalgia here for British times - no Maltese would want a return to colonial rule. But nor is there the slightest trace of hard feeling.

"The British period is part of our heritage," my friends tell me, "and the Queen is always very welcome here."

Perhaps the next restoration project should be Villa Guardamangia. Apparently the Queen asked to see it last time she was in Malta but was refused because of its dire state of repair. Maybe, one day, Her Majesty should drop by and have a private word with the grumpy lady at the top-floor window.

The Magazine on Malta

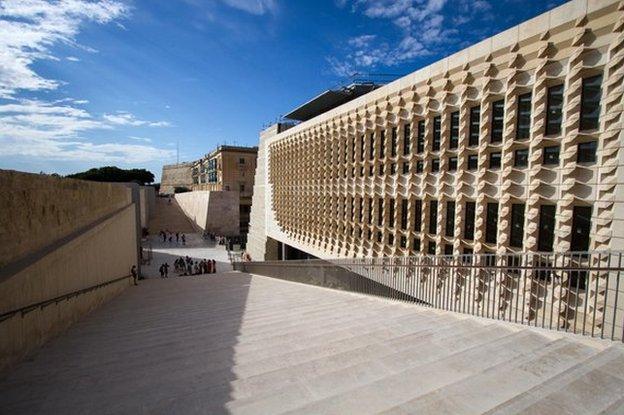

In recent years Malta has challenged its conservative image, legalising divorce and same-sex partnerships. The spirit of reform has also breached the imposing walls of the capital, Valletta. The 16th Century city was built in the local honey-coloured limestone by the Knights of St John but the entrance and the square just inside it have been dramatically redesigned by Renzo Piano, the innovative Italian architect of the London Shard.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.