Why do people resent buy-to-letters so much?

- Published

A series of measures have now been taken to combat the growth of buy-to-let landlords, and each is greeted with glee by an often hostile public. But why do many people resent buy-to-letters so much, asks Gareth Rubin.

If you type "buy-to-let landlords are" into Google, its auto-complete function adds a very uncomplimentary word to the end of the sentence.

A series of measures have recently been taken in the UK against small investors who buy additional houses to rent out. In the summer, it was announced the tax relief on their mortgage interest payments would be reduced. They will face a higher rate of stamp duty on house purchases. Now Bank of England Governor Mark Carney says further action will be taken on the buy-to-let market because of the danger of a future financial crash being exacerbated.

Visit the comments at the bottom of a news story and you'll see a wave of hostility. One reads: "I really cannot wait for the stampede as the BTL parasites all start panic selling when the bubble bursts." Another: "BTLs are just another business created for greed, not for homing people." Someone comments: "The worst type of human - those greedy, vulture like exploiters."

Over and again, words such as "greed" and "parasites" come up. And when many of the landlords reply on the same forums saying that they have worked hard all their lives, saved up some money and that this is to be their pension in old age, those claims are dismissed as "'I provide a service' baloney".

"Landlords are greedy. They greedily ratchet up the rent at every opportunity and therefore get the consequences," says Robert Stevens. It's his simple answer to the question of why buy-to-let landlords - of whom there are now estimated to be as many as two million in the UK, external - have, over the past few years, started to become as unpopular as wheel-clamping services or cold-calling PPI refund firms.

Renting in the UK - a history

But Stevens isn't some aggrieved tenant, housing campaigner or left-wing academic. He's a buy-to-let landlord with eight properties who is exasperated at the behaviour of many of his fellow businesspeople.

Newspaper columnists, activists and politicians regularly brand them as unhelpfully leeching off those who are unable to get a foot on the housing ladder.

According to Stevens, the landlords' poor business decisions are partly to blame for the crushed dreams of their tenants: "In the old days, you used to rent a property while you built up capital to put down as a deposit on a property you buy. But landlords are mortgaged up to the hilt now so they have to charge very high rents, and that means tenants can't save for a deposit." So, in Stevens's view, those greedy landlords over-stretching themselves in the past few years have actually resulted in their tenants being trapped in the rented sector.

In England alone, the government's 2014 Housing Survey, external found that 19% of households were in the private rented sector, occupying around 4.4 million homes. This was a huge increase from 11% in 2003. And the number keeps rising.

According to the Association of Residential Lettings Agents, the average British landlord is 56, owns eight rental properties and has already been a landlord for 14 years - not quite the stereotypical image of a retired couple with a little flat that they let to supplement their pension.

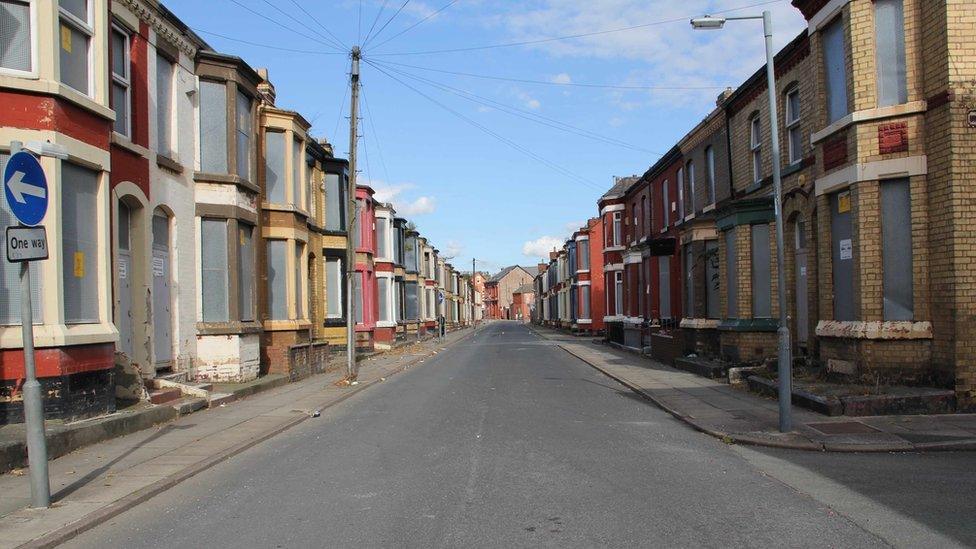

Tony McVey, president of the North West Property Owners Association, who himself owns 12 rental properties in Liverpool, understandably feels landlords are often treated unfairly in public discourse. "We're an easy target. We've always been held in contempt and the government now seems to have concentrated its efforts on making our lives even more difficult," he says.

"I'm used to it, but I still resent it. And no one seems to hold the tenants to account - but aren't they part of the process too? Of course there are poor landlords, but there are also poor lawyers and poor journalists, but most landlords are amateurs so we're easy targets."

The proposed measures

In July, the Government announced that buy-to-let landlords would face cuts in the amount of tax relief they could claim on mortgage interest payments - to 20%, from 45% for the wealthiest.

In September the Bank of England's Financial Policy Committee (FPC) warned about the buy-to-let market saying it had the ability to "amplify" a housing boom or bust.

Since the FPC's warning, the chancellor announced that stamp duty rates will rise steeply for anyone buying a home that is not their main residence.

The stamp duty surcharge would lift each band by 3% meaning that for properties worth between £125,000 and £250,000, where the stamp duty is 2%, buy-to-let landlords will pay 5%.

But commercial property investors, with more than 15 properties, are expected to be exempt from the new charges.

Buy-to-let landlords will also be hit by a change to Capital Gains Tax (CGT) rules - from April 2019 having to pay any CGT due within 30 days of selling a property, rather than waiting till the end of the tax year.

Teacher Helen Kinsey, 50, recently had to leave her home in south London, after living there for 21 years, when her landlord demanded a 30% rent rise. "I think people feel this animosity towards landlords because there are so many stories like mine," she says. "Property prices have risen drastically in London because all the new-builds are being advertised throughout the world for investors who are leaving them empty. That's putting pressure on prices. Greedy landlords and greedy developers and greedy agents are seeing an opportunity to keep pushing the rent up. So normal people like me are being pushed out."

But there's probably another factor at play. David Savill, a 39-year-old lecturer from London who is married with two children, has been renting since he left university nearly 20 years ago. "If I'm being honest, as one of the new middle-aged tenants who had thought that by now in his life he would own a house, there's lots of resentment there towards people who own and let houses, and seem to be sucking all the equity out of the economy when that's what I wanted to do," he says. "And the resentment comes from the thought that you've paid off their mortgage and then some."

And yet it's harder to understand why landlords are often on the receiving end of such anger from people among the 81% of households who do not live in private rented accommodation.

Alison Wallace, an academic at York University, has researched the buy-to-let sector. She says some of the public animosity is a result of the financial sector stacking the odds in the favour of landlords, and that makes the property market dysfunctional for everyone. "Interest-only mortgages are offered to buy-to-let landlords but not first-time buyers, so landlords have lower payments and that means they can outbid the first-time buyers. And that makes the whole market more frothy," she says.

But behind the economics, there is probably something more basic - our need for a home. And when someone appears to be exploiting that need, it causes widespread anger. As Dan Wilson Craw, from campaign group Generation Rent, which speaks for young tenants, says: "Most people just want a place to live, whereas buy-to-let landlords want a place to make money." Landlords are fundamentally abusing what housing is, he claims.

Kinsey agrees. "A home is really vital to your mental health and there are times when I've nearly gone under with the pressure and instability of it all," she says. "The law puts all the power in the hands of landlords. It's just wrong. It's immoral."

The Magazine on housing

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.