How it helps, in France, to have a bit of 'piston'

- Published

There's a great French word "pistonner" - from piston, a noun that English shares with French. Basically, "pistonner" means to give someone a leg-up. If you say you've got "du piston", it means you know somebody in some position of influence, who might be inclined to help you.

As a foreigner in France, all you can do is look on and observe how the system works. Everybody knows that in job recruitment, for example, it still counts for a lot to have someone put a word in. The idea of oneself having a bit of "piston", well it's all a bit unlikely. Until the day comes... well, let me tell you the story.

First of all I need to introduce you to a man called Pascal Cherki. Pascal Cherki is my MP in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, and until a few months ago he was my mayor. Actually for several years, he was both. That's the way things often are in France. They have people called depute-maires, which doesn't mean they are deputy mayors. It means they are both parliamentary deputies (MPs) and mayors - useful people to have in your address book.

Pascal Cherki - bear-like in parliament

Well, independently of my living in his constituency around Montparnasse, I'd got to know Cherki because of who he is. Cherki's what in British terms would be called a left-wing rebel. In France, he's a frondeur. If you know your French history, you'll remember that the "fronde" was the long revolt against the crown during the boyhood of Louis XIV.

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30

Cherki's inevitably been nicknamed Sharky in the BBC office, but it's a ludicrously inappropriate soubriquet. There's nothing sharky about him at all. The name is actually Algerian Jewish, and comes from the Arabic "Sharqi", meaning from the East. No, Pascal Cherki is a big, humorous, unkempt, grizzly bear of a man. But he's a ready talker, got pretty good English, and over the years he's appeared pretty regularly on our programmes.

Which is why on a morning last week, as I wandered distractedly through the salles des Quatre Colonnes (that's like the lobby) in the National Assembly, simultaneously gnashing my teeth and gnawing my lip over a pretty fix I was landed with, my heart lit up when I saw the ursine figure of Monsieur Cherki lumbering towards the chamber.

What had happened is that my daughter Ruby had just had her application for a Russian visa turned down. She's studying Russian, and she needs to spend six months in Tomsk. But her passport is Irish, and to get a visa in Paris she needs to have a document stating that she is resident here.

The fact that she's lived in Paris practically all her life counts for nothing, unless you can prove it - and we suddenly realised that we couldn't.

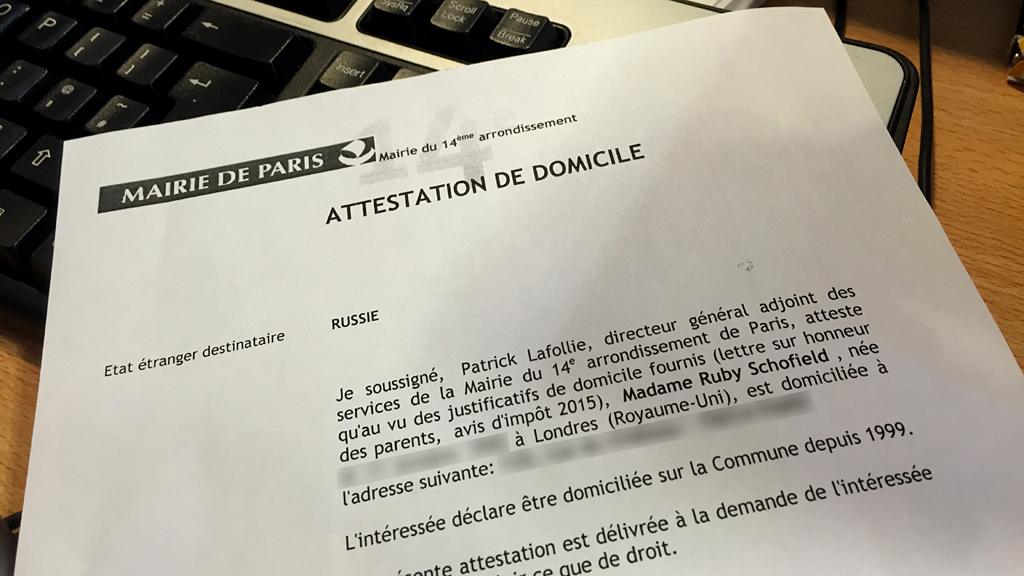

A generic letter from the Mairie wasn't enough to confirm that Ruby was a resident

First port of call was the town hall, or Mairie, of the 14th, where they gave us a piece of paper saying she said she lived here. But that was really no good. At the Russian embassy they took one look and, "Nyet". Not enough. Ruby's residence had to be officially attested - signed and stamped in the original, by a person of rank. Back at the guichet in the Mairie, the blank stare of the petty bureaucrat, "Mais on fait pas ça nous". "Sorry, not our job."

It was getting Kafka-esque. We needed an official document that didn't exist. With practised indifference, two sets of desk-wallahs were ping-ponging us one to the other, and unless something happened fast, Ruby was not going to make her plane. And then I saw Sharky.

It was a big day in parliament - a rebellion brewing over the president's constitutional changes. "Monsieur Cherki," I call. He's all smiles. We discuss the government's predicament, and then the conversation slides. "Very sorry to bring this up... ahem... trivial problem... long-time constituent... no other recourse."

A little help from friends in high places

Sharky didn't blink. A biro and a piece of paper, a scribbled email address - which I contacted the next morning - and there I was soaring with self-satisfaction. How great am I, to know The Man?

Since then my mind has become somewhat troubled. Personal connections are fantastic - if you have them. I'd had luck and a way in, thanks to my job. What if I hadn't? Was this all strictly ethical? Had I broken BBC guidelines?

But then I think, "Baah - what counts is the result."

And anyway, what a feeling. After 20 years living in France, for the first time, I've got "du piston".

More from the Magazine

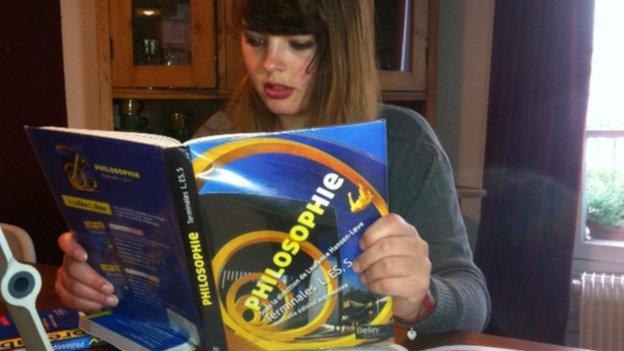

I have been staring in admiration over the shoulder of my 17-year-old daughter, as she embarks on a last mental rehearsal before a much-dreaded philosophy exam. Ruby has chosen to take what they call a Bac Litteraire - the Literature Baccalaureate.

There are alternative, more science-biased versions of the Baccalaureate. They all include an element of philosophy. But in the Bac Litteraire, philosophy is king.

Read the full story: Why must French pupils master philosophy? (2013)

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.