Could Stoke be City of Culture?

- Published

Is there more to culture in Stoke than its world-famous potteries?

If you want a proper cup of tea from a proper teapot, the place to go is Stoke-on-Trent - not so much for the tea itself as because the chances are it'll be served in decent china.

Ceramics, after all, are what they do here - the six towns that came together in 1910 to form Stoke-on-Trent were known as The Potteries. Like most of the cities applying to be city of culture in 2021, Stoke's bid makes the most of its heritage, but like its rival Paisley (famous for Paisley shawls and the Paisley pattern) that heritage has a distinctly artistic flavour.

Making pottery is a job that fuses art and technology, the creative with the scientific. In the industry's heyday it employed thousands of artists - from designers and highly-skilled engravers to the humble folk who actually applied the decoration to Staffordshire tableware and ornaments. These days the big factories making cheap goods for the mass market have mostly gone - it's much more cost-effective to manufacture in the Far East - but there are still plenty of potteries. Indeed the industry in Stoke has enjoyed a modest revival in the past few years, producing mainly high-end, luxury goods.

Stoke's potteries in 1948

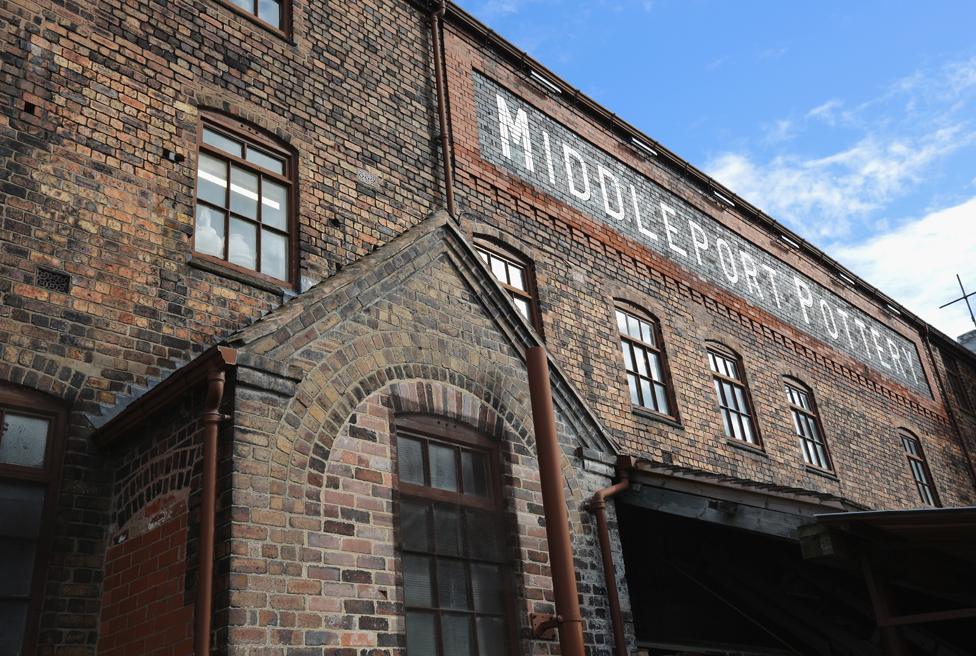

We went to Middleport Pottery, the home of Burleigh, a famous name in ceramics, and of the BBC's Great Pottery Throw-Down. These days it's a tourist attraction as well as a factory, a wonderfully-preserved Victorian workspace acquired and restored by the Prince's Regeneration Trust in 2011 - though only one of its seven distinctive bottle ovens still stands.

Messrs Burgess and Leigh moved to their purpose-built "model pottery" at Middleport in 1888. They still make cups and saucers here by hand, applying patterns printed on cigarette paper - the unglazed "biscuit" absorbs the ink from the paper, which is then washed off before the piece is glazed and fired, leaving an indelible pattern under the glaze. The whole thing is done by hand.

Steven Moore is Burleigh's creative director, and a resident expert on the Antiques Roadshow. "Because it's a handmade process and because the prints are done every day they have a subtlety and a depth of colour that you simply can't get by mechanical means," he told me. Like everyone we met in Stoke, he's an enthusiast for the city of culture bid: "Anything that shines a spotlight on Stoke benefits us too, which can't be a bad thing."

The historic Middleport Pottery

It's a view shared by the tenants in the artists' studios downstairs. Jade Simpson makes sculptures that look like stuffed animals (in fact they're made with felt and papier mache) in a studio she shares with her twin sister Jessica and Alex Allday, both ceramicists. Being city of culture would give young artists like her a reason to stay in Stoke, she tells me, and help their careers. It would be "good ammo", offering more potential for funding and recognition.

Another potter, Liz Slinn in the studio next door, thinks many people are still passionate at the loss of Stoke's ceramics industry and that city-of-culture status would help to revive it. It might also, she suggests, help to widen the local definition of culture beyond ceramics.

It's true that ceramics constitute a large part of Stoke's present appeal to visitors. Drive round the city and you can't miss the many brown tourist signs for famous-name potteries (or their factory shops). Tourists come from all over the world - in particular China, Japan and Korea.

But there's also plenty of culture in Stoke which isn't potbound. Up the hill a few metres across the border into neighbouring Newcastle-under-Lyme is the New Vic theatre, a regional producing house which is rehearsing a revival of a Victoria Wood play on the day we visit. Fiona Wallace, the theatre's executive director, thinks the city is an ideal city of culture candidate.

New Vic Theatre, Newcastle Under Lyme

"Here we are in the New Vic theatre," she tells me as we sit talking in the theatre's workshop. "We make theatre locally, our painters are working next door, our costume team are working just down the hallway, we have a show in rehearsal. We still make high quality art here and we want to share that with the world. But we also want the world to come here and share their art and culture with us."

The city centre - which is in Hanley, one of the six original towns - boasts a "cultural quarter" with another major theatre, the Regent, which hosts touring West End shows and is jointly managed with the 1,400-seat Victoria Hall behind Hanley town hall. Nearby is the rather grand Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.

In the surrounding streets you'll find a series of pop-up businesses run by and for artists, a sign of the city's busy contemporary arts and music scene - streetware store Entrepreneurs, for instance, with its upstairs gallery showcasing urban art, and music venue The Sugar Mill, with a vast street art mural on its facade.

But the reason they can afford the rents is that commercial businesses are moving out. Piccadilly, the pedestrianised street in the heart of the quarter, is a forest of "To Let" signs. Stoke has been suffering economically from the closure of not just the big potteries but coal mines and other manufacturing businesses. That's had knock-on effects - Andrew Nicklin, the general manager of the Regent and Victoria Hall, tells me only 40% of his audiences come from Stoke itself, which suggests a local population many of whom are too poor or too apathetic to bother with live entertainment.

You can see the effects of post-industrialisation all over the city - large mysteriously empty sites next to main roads, crumbling, empty factories and warehouses, boarded-up pubs and shops.

In the centre of Stoke, another of the six towns and the one with the railway station and city council offices, there's a prime example - the old Spode factory, "the birthplace of bone china", which finally closed in 2008. But here the city council bought the site, and the current administration, a coalition of independent, Conservative and UKIP councillors in a traditionally Labour-dominated area, is treating it as a centrepiece of its culturally-led regeneration strategy.

The rather grand entrance to the site is being done up. Parts are being sold off for redevelopment as student accommodation, other parts are being developed as artists' studios and workshops. The main hall of the old factory is in use as an exhibition space - every two years it hosts the British Ceramics Biennial. In the dilapidated street outside, otherwise empty shops have been handed over to more pop-up arts organisations like Pilgrim's Pit, a coffee shop-cum-record store-cum-general hang-out for artistic types.

The Spode factory, now being redeveloped by the local council

Abi Brown, the council's deputy leader, does a good job in talking up the city - its central geographic position, its good transport links (midway between Manchester and Birmingham, 90 minutes by train to London), its ceramics heritage. She also admits that Stoke folk are "naturally self-deprecating". Much of the council's effort is focused on trying to instil a greater sense of civic pride.

Paul Williams, who runs the business school at Staffordshire University in Stoke, echoes that. He's one of the prime movers behind the city of culture bid. He was also brought up in Liverpool, not Stoke. "We're actually quite insular in many ways," he tells me. "We don't shout out about the wonderful assets and the wonderful offer we have here. Contrast that with Liverpool - people in Liverpool will tell the world it's the greatest city on the planet. I actually think Stoke-on-Trent has a comparable right to say it's a great city, it's got some amazing things to offer and it's time we started to shout about that."

But he says local people have to buy into the idea first that "Stoke's no joke" (to quote a recent social media hashtag) and that culture is something everyone can engage with. He cites the Stoke Literature Festival, hosted by another local pottery, Emma Bridgewater, which has developed a series of initiatives to engage young people.

A statue of Sir Henry Doulton, founder of Royal Doulton China, overlooks Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent

"It's about trying to raise aspirations," he says, and help the young to grasp opportunities in the knowledge economy, the digital economy and an economy focused on the creative and cultural industries.

Separately, he admits, Stoke needs to address some of its other shortcomings - like a shortage of hotels - if it's to win the city of culture bid.

One thing the city isn't short of is dynamic individuals keen to make a success of the bid. I am especially impressed by two of those I meet.

One is Andy Cooke, a graphic designer by trade - he's designed the Stoke city of culture bid identity - and one of the first tenants in the new artists' workshops at Spode. He's also one of the partners in the Entrepreneurs streetware store - whose spin-offs include a creative screenprinting workshop and a scheme to help local graffiti artists. And he's a partner in a pizza restaurant called Klay which recently opened in the cultural quarter.

He too thinks Stoke has a bad reputation as a run-down, post-industrial city. "It's going to take a while to shift that stigma," he tells me. "But other cities have done it in the past 10 or 20 years and there's no reason why Stoke can't do it too."

The other is Susan Clarke, founder and artistic director of B Arts, a community arts group which has been going for 30 years. Operating from a converted garage just up the road from Spode, its recent initiatives include lantern parades, civic celebrations and an Art City programme focused on using redundant buildings and spaces in the city as temporary sites for artistic activity. Oh, and it's recently opened a bakery.

She's also the creative programme director for the city of culture bid, in which capacity she is already thinking up ideas - a sculpture trail, perhaps, which doubles as a cycle path and opens up the city's green spaces and the canal that connects five of the six towns.

"What the city of culture is for is not just celebrating what you've got now but asking how do you build a credible future for your city," she says. "It reminds everybody that we can all do something. Thinking with our hands, you can be the author of your own destiny, you can be the poet, you can be the author, you can be the person who can make your own future."

City of culture contenders profiled in the Magazine

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.