'I was sterilised against my will'

- Published

After an emergency caesarean, Victoria Vigo found she had been sterilised - despite not having given her consent. Like many others who endured the same treatment, she is demanding justice.

"I wanted to have more children, but that choice was taken away from me without my permission - that was my decision to make not theirs."

In April 1996, mother-of-two Victoria Vigo was living in the hot, coastal city of Piura in north-western Peru.

"I was 32 weeks pregnant and I wasn't feeling very well, so I went to see my doctor," she says. "He sent me to hospital where I ended up in accident and emergency. They evaluated me and decided to carry out an emergency caesarean."

Vigo's baby was born with breathing difficulties, his premature lungs weren't properly developed and he died soon after.

"There was a doctor trying to console me saying: 'Don't worry, you are still young, you can have another baby.'"

But Vigo, who was then aged 32, then overheard another doctor say: "No, she can't have any more children, we've sterilised her."

Vigo is just one of around 300,000 people estimated to have been sterilised against their will in Peru between 1996 and 2000, when then-president Alberto Fujimori embarked on a family planning programme known as Voluntary Surgical Contraception, part of an anti-poverty drive.

In 1997, Vigo began her fightback against the authorities.

"It wasn't just about my rights, I soon realised that this was part of a national policy and there were many other women involved," she says.

"This was going on all over Peru with doctors making decisions without properly consulting the women involved."

After years of legal disputes Vigo eventually won her case and was awarded damages of approximately £2,000 in 2003. She is the only person in Peru who has received any form of compensation after being forcibly sterilised.

The men and women targeted under the sterilisation programme were usually poor, indigenous Quechua-speakers, many of whom signed a piece of paper written in Spanish that they didn't understand.

Fujimori had said it would be a progressive plan offering a wide range of contraceptive methods, including surgical sterilisation, which had previously been illegal in Peru.

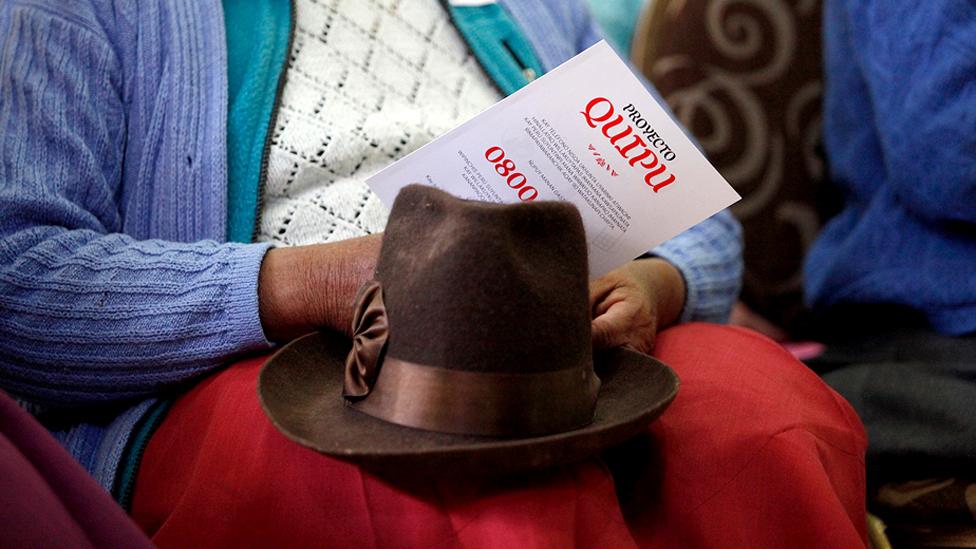

"But the truth is that instead of promoting a range of contraceptive methods there were targets, quotas and numbers of sterilisations that the health personnel had to achieve," says Rosemarie Lerner, director of the Quipu project, external, which collects and shares the testimonies of people like Vigo who were forcibly sterilised in 1990s Peru.

Quipus were an ancient recording system of threads and knots used by the Incas and ancient Andean cultures to keep records. "We have chosen the Quipu to symbolise this project because we too are recording oral information, prompting our collective memory to ensure that the sterilisations are not forgotten," the project's website says.

Under the Quipu project, people across Peru can use a free telephone line to share their stories, listen to the testimonies of others and record responses. Once recorded, the messages are translated into Quechua, Spanish and English and uploaded to the project's website where they can be listened to from anywhere in the world.

'I woke up hours later. There was a cut across my belly' - hear one woman's testimony

Lerner's team have been running workshops around the country to show people how to use the Quipu project website and telephone line to submit their stories. The team are currently collecting testimonies in the Amazon jungle. Last year they were in remote Andean communities.

"Most of the stories have a common structure," she says. "How the sterilisation campaign started, how the nurses or medical personnel came looking for women in their houses, then the actual moment of the operation and how traumatic it was - some women were even sterilised while pregnant."

There are testimonies from women who describe being coerced into being sterilised in return for food or medicine. Many say the often botched operations - some of which were carried out without general anaesthetic - have left them so badly injured they are unable to work. Offered no aftercare, the women describe feeling marginalised because they can no longer work and believe they have no societal value since they can no longer bear children. Many describe how their relationships have deteriorated or fallen apart.

Talking about the forced sterilisations is still considered taboo for many in Peru, but Lerner hopes that the Quipu project will help challenge attitudes.

"We want the women who take part in the Quipu project to understand that they're not alone," she says. "Thousands of them went through the same experience and they deserve to be heard."

In 2003, three years after Fujimori was forced from power, Peruvian prosecutors began investigating allegations of forced sterilisations. Since then a number of investigations have been opened and then shelved - the most recent was shelved for a second time in December 2016 when the court said there wasn't enough evidence to proceed.

The former president is currently serving a 25-year prison sentence for embezzlement and human rights abuses committed during his decade-long time in office.

Find out more

Hear more about the Quipu project on Outlook on the BBC World Service

But most of those who were sterilised are still waiting for justice.

Vigo acknowledges that she probably succeeded in suing for damages because unlike most of the other people who were sterilised against their will she is middle class, educated and speaks Spanish.

Despite the compensation she has already received, Vigo says that she and the others still need recognition.

"We want to get proper compensation, but it's not just about the money. We need proper justice for what has happened," she says.

"It was racist to think you can target the poorest and most vulnerable members of society and make decisions for them. How is it possible to treat women like that in the 21st Century? They violated our human rights and our right to decide our future for ourselves."

All images courtesy of the Quipu project, external unless otherwise stated

Hear more about the Quipu project on Outlook on the BBC World Service

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.