Why were 101 Uzbeks killed in the Netherlands in 1942?

- Published

They left their homes in Central Asia to fight against the German army. Then, dressed in rags, they were taken as prisoners to a concentration camp in the Netherlands. Few now alive remember the 101 mostly Uzbek men who were killed in a forest near Amersfoort in 1942 - and they may well have been forgotten entirely if it had not been for a curious Dutch journalist.

Every spring hundreds of Dutch men and women, young and old, gather in a forest near the town of Amersfoort, near Utrecht.

Here they light candles to commemorate 101 unknown Soviet soldiers who were shot dead by the Nazis at this very spot - and then forgotten for more than half a century.

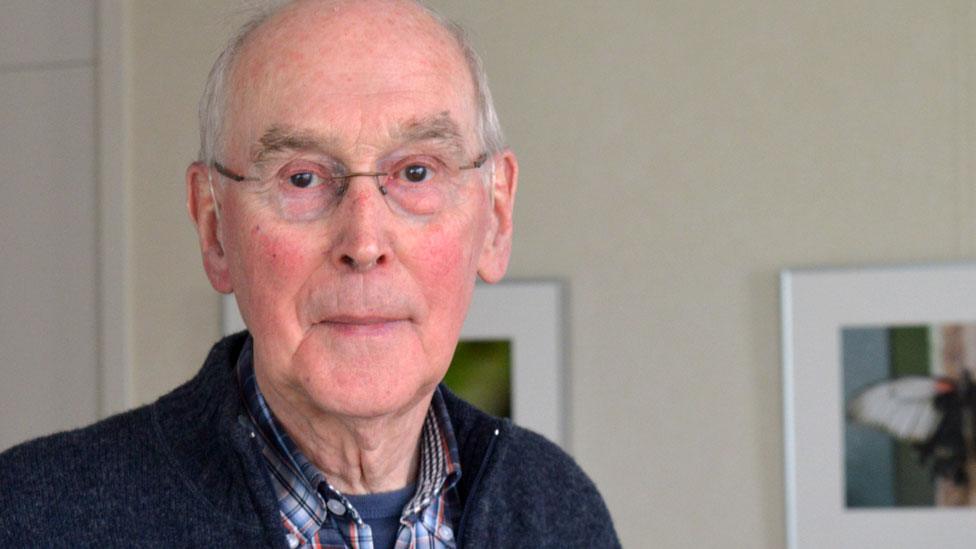

The story was rediscovered 18 years ago, when journalist Remco Reiding returned to the town after working in Russia for several years, and heard from a friend that there was a Soviet war cemetery nearby.

"I was surprised as I never heard of it before," Reiding says. "I visited the place and started looking for archives and witnesses."

It turned out that 865 Soviet soldiers were buried there, all but 101 of them brought from other parts of the Netherlands or Germany.

But the 101, all unnamed, had died in Amersfoort itself.

They had been captured near Smolensk in the first weeks after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, and transported to the German-occupied Netherlands for propaganda purposes.

"They handpicked the Asian-looking prisoners and wanted to exhibit them to the Dutch, who resisted Nazi ideas," says Reiding.

"They called them untermenschen - inferior people - and hoped that once the Dutch saw what the Soviets looked like, they would join the Germans."

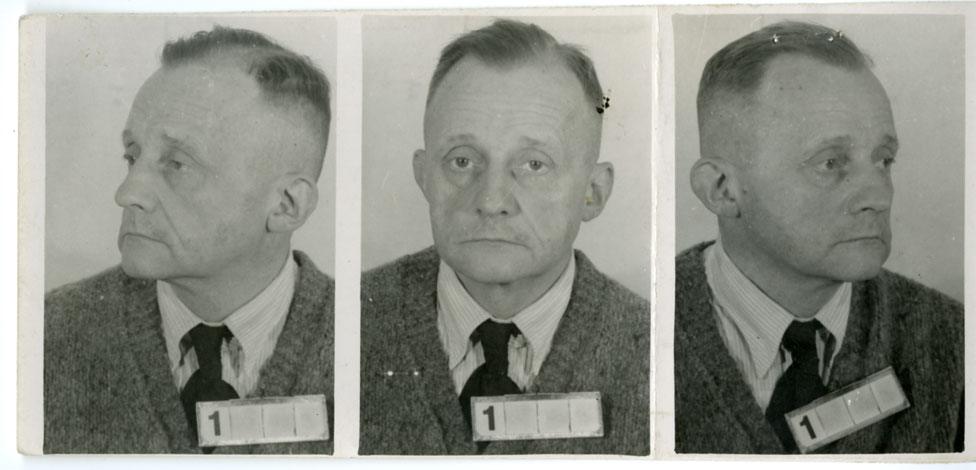

Camp Commander Karl Peter Berg was executed by firing squad in 1949

It was Dutch communists held in a concentration camp in Amersfoort whose opinion of the Soviet people the Germans were expecting to change. They had been held there with local Jews since August 1941, while all of them waited to be moved to other locations.

But the plan didn't work.

Now 91, Henk Broekhuizen, is one of the few remaining witnesses. He remembers, as a teenager, watching the Soviet prisoners arriving in the town.

"When I close my eyes I remember their faces," he says.

"Wrapped up in rags, they didn't even look like soldiers. You could only see their faces.

"The Nazis paraded them through the main street all the way from the train station to the camp. They were weak and small, their feet were covered in old cloths. Some of them could hardly walk and their friends helped them."

Some prisoners managed to make eye contact with the onlookers and used hand gestures to indicate that they were hungry.

"We brought some water and bread for them," says Broekhuizen. "But the Nazis knocked it all from our hands. They didn't let us help them."

He never saw them again and heard nothing of what happened to them in the camp.

But Reiding started gathering evidence from Dutch archives.

One thing he discovered was that they were mainly Uzbeks. The camp authorities themselves were unaware of this, until an SS officer who spoke Russian arrived to interview them.

The translator, Alscher, had picked up Russian in Poland

Most were from Samarkand, says Reiding. "Maybe some of them were Kazakh, Kyrgyz or Bashkir. But the majority were Uzbeks."

Reiding also learned that the Central Asians were treated worse than any of the camp's other prisoners.

"The first three days in the camp the Uzbeks are kept without food, outside, surrounded by barbed wire," says Reiding.

"A German film crew prepares to capture the moment when the 'barbaric sub-humans' fight over food - they need to film this scene for their propaganda.

"So the Nazis throw a loaf of bread to the hungry Uzbeks.

"To their surprise, one of them takes the bread and calmly divides it into equal pieces with a spoon. The others wait patiently. No-one fights. Then they share the evenly divided pieces of bread. The Nazis are disappointed."

Remco Reiding has traced the families of 200 of the 865 Soviet soldiers buried at Amersfoort

But worse was to come for the prisoners.

"The Uzbeks were given half as much food as the others and if any other prisoner helped them the whole camp was left without food as punishment," says Bahodir Uzakov, an Uzbek historian based in nearby Gouda, who has also been researching the story of the Amersfoort camp.

"When they ate leftovers and potato skins the Nazis beat them for eating pigs' food."

From the confessions of camp guards and the recollections of prisoners he found in the archives - which formed the basis of his 2015 book, Child of the Field of Honour - Reiding also learned that the Uzbeks were constantly beaten and given the worst jobs, such as carrying heavy masonry, sand or logs in the cold.

One of the most shocking stories he discovered is about the camp doctor, a Dutch man called Nikolaas Van Nieuwenhuysen.

When two of the Uzbeks died, he forced other prisoners to behead them and boil their skulls until they were clean, Reiding says.

Dr Nikolaas Van Nieuwenhuysen was sentenced after the war to 10 years in jail

"The doctor kept the skulls of two Uzbeks on his desk to study. How crazy!"

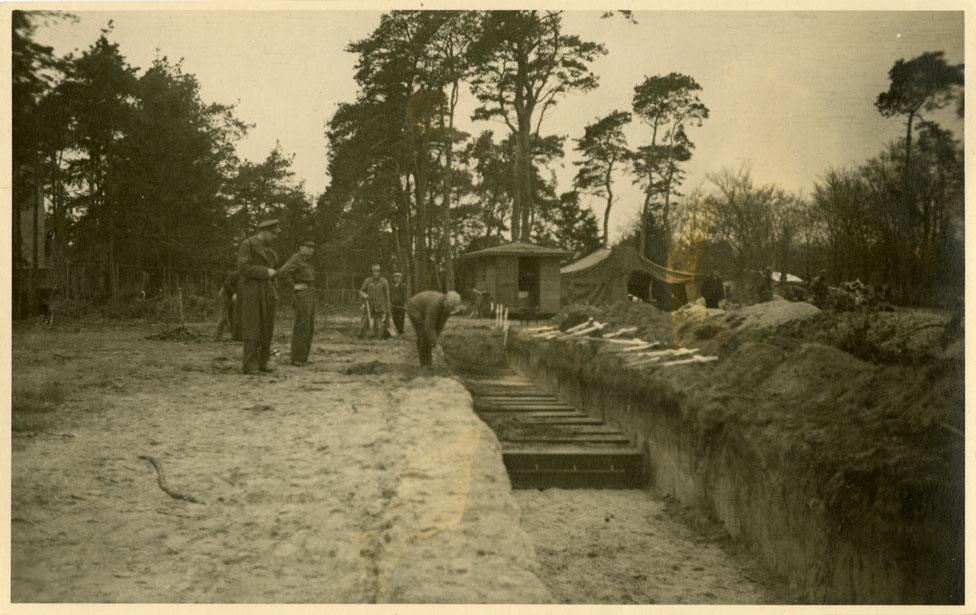

Starved and frail, the Uzbeks started eating rats, mice and plants. Twenty-four of them didn't survive the harsh winter of 1941, and the remaining 77 were no longer needed when they became too weak to work.

So early one morning in April 1942, the Nazis told them they were being moved to southern France, where the warmer climate would suit them.

In fact they were taken to a forest just outside the camp, where they were shot and buried in a mass grave.

"Some of them started weeping, some held hands together and faced their death. Those who tried to flee were chased by the soldiers and shot," says Reiding, quoting camp guards and drivers who witnessed the execution.

Two rows of headstones inscribed "Unknown Soviet Soldier" in Russian mark the graves of the 101 Central Asians

"Imagine being 5,000km away from home - where the muezzin calls people to prayer, where the wind plays with the sand and dust on the market square and the streets are filled with the aroma of spices. You don't know their language and they don't know yours. And you never understand why these people treat you as if you were an animal."

There is little information that might help to identify these prisoners. The Nazis set fire to the camp archives before they fled in May 1945.

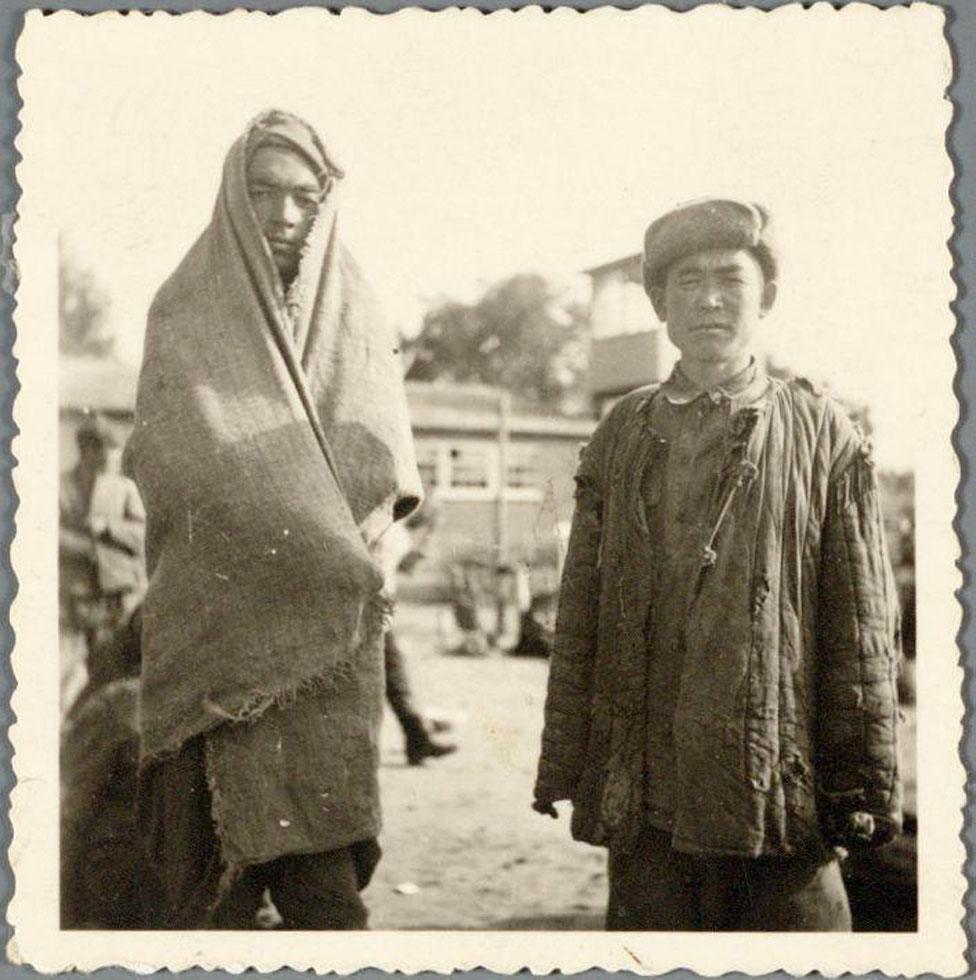

There is only one photograph that shows faces - two men, neither of whom are named.

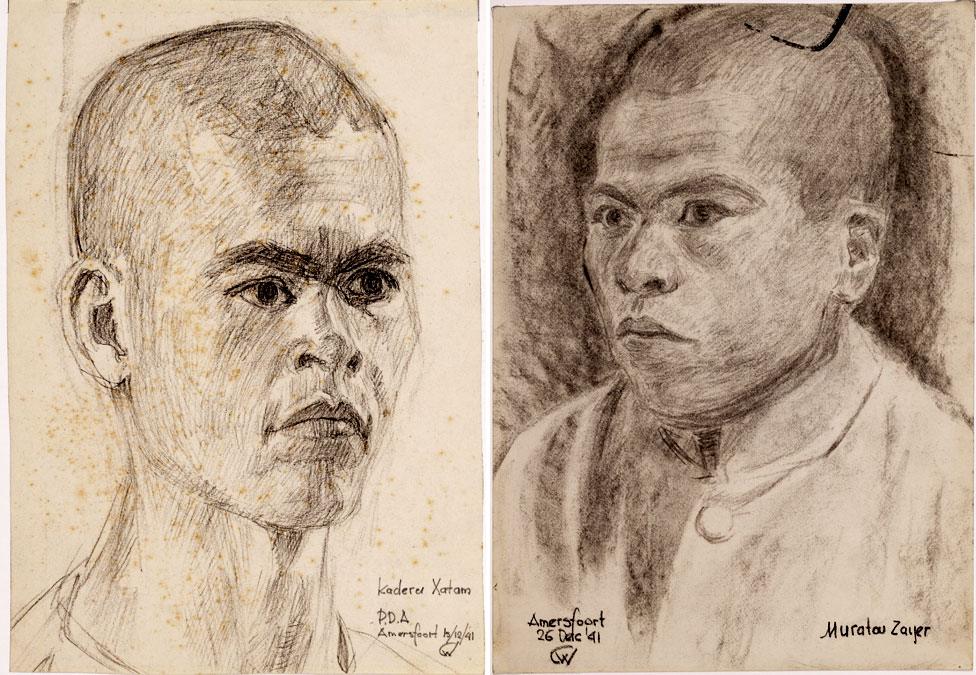

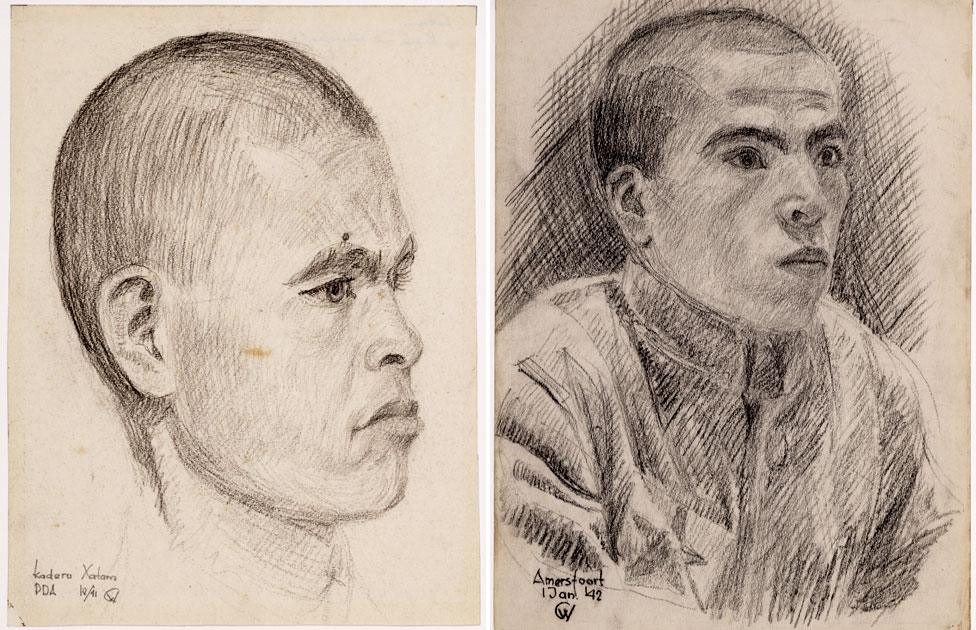

Of nine portraits drawn in pencil by a Dutch prisoner, only two have names.

"The names are misspelt but they sound Uzbek," says Reiding.

"One is Kadiru Xatam and another says Muratov Zayer. So the first should be Kadirov, Hatam and the second is Muratov, Zair."

Hatam Kadirov and Zair Muratov

I instantly recognise the Uzbek-sounding names and the Central Asian faces. The unibrows, gentle eyes and mixed-race features - these are all considered beautiful in my country.

These are portraits of young men in their early twenties, or even younger. Probably their mothers had already begun looking for suitable brides and fathers had already bought a calf to rear for their wedding feast, when the war intervened.

It occurs to me that some of my own relatives could be among them. Two of my great uncles and my wife's grandfather failed to return from the war.

Sometimes I was told my uncles had married German women and decided to stay in Europe - a story my grandmothers invented to console themselves.

In fact, a third of the 1.4 million Uzbeks who fought in the war did not return and at least 100,000 remain missing.

Another drawing of Hatam Kadirov (left) and an unnamed prisoner, possibly also Zair Muratov

There are many reasons why the 101 Uzbek soldiers buried in Amersfoort have never been identified - apart from the two whose names are known. One is the Cold War, which followed quickly after World War Two, and turned Western Europe and the USSR into ideological enemies.

Another is Uzbekistan's decision to forget its Soviet past, after gaining independence in 1991. Veterans were no longer considered heroes. A monument to a family that adopted 14 war orphans was removed from a square in the centre of Tashkent - though the country's new president now says it will be returned. In short, looking for soldiers that went missing in the Soviet army several decades ago has not been a priority for the Uzbek government.

The Uzbeks were moved from the mass grave to a cemetery, then moved again when a special cemetery for Soviet war dead was created

But Reiding thinks he may be able to find the names in Uzbek archives.

"The documents of those Soviet soldiers who didn't die or whose deaths were not known to the Soviet authorities were sent to the local KGB, and the identities of the 101 prisoners are probably kept in Uzbekistan," says Reiding.

"If I have access to them I can find some of the 101 Uzbeks."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.