Ancient language mystery deepens

- Published

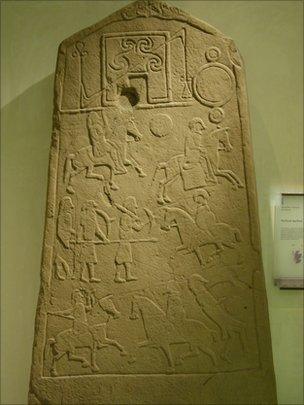

Many of the stones are believed to have been carved during the 6th Century

A linguistic mystery has arisen surrounding symbol-inscribed stones in Scotland that predate the formation of the country itself.

The stones are believed to have been carved by members of an ancient people known as the Picts, who thrived in what is now Scotland from the 4th to the 9th Centuries.

These symbols, researchers say, are probably "words" rather than images.

But their conclusions have raised criticism from some linguists.

The research team, led by Professor Rob Lee from Exeter University in the UK, examined symbols on more than 200 carved stones.

They used a mathematical method to quantify patterns contained within the symbols, in an effort to find out if they conveyed meaning.

Professor Lee described the basis of this method.

"If I told you the first letter of a word in English was 'Q' and asked you to predict the next letter, you would probably say 'U' and you would probably be right," he explained.

"But if I told you the first letter was 'T' you would probably take many more guesses to get it right - that's a measure of uncertainty."

Using the symbols, or characters, from the stones, Prof Lee and his colleagues measured this feature of so-called "character to character uncertainty".

They concluded that the Pictish carvings were "symbolic markings that communicated information" - that these were words rather than pictures.

Prof Lee first published these conclusions in April of this year. But a recent article by French linguist Arnaud Fournet opened up the mystery once again.

Mr Fournet said that, by examining Pictish carvings as if they were "linear symbols", and by applying the rules of written language to them, the scientists could have produced biased results.

He told BBC News: "It looks like their method is transforming two-dimensional glyphs into a one-dimensional string of symbols.

"The carvings must have some kind of purpose - some kind of meanings, but... it's very difficult to determine if their conclusion is contained in the raw data or if it's an artefact of their method."

Mr Fournet also suggested that the researchers' methods should be tested and verified for other ancient symbols.

"The line between writing and drawing is not as clear cut as categorised in the paper," Mr Fournet wrote in his article. "On the whole the conclusion remains pending."

But Prof Lee says that his most recent analysis of the symbols, which has yet to be published, has reinforced his original conclusions.

He also stressed he did not claim that the carvings were a full and detailed record of the Pictish language.

"The symbols themselves are a very constrained vocabulary," he said. "But that doesn't mean that Pictish had such a constrained vocabulary."

He said the carvings might convey the same sort of meaning as a list, perhaps of significant names, which would explain the limited number of words used.

"It's like finding a menu for a restaurant [written in English], and that being your sole repository of the English language."