Bloodhound diary: The '1,000mph genome'

- Published

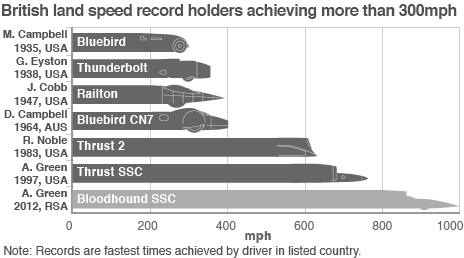

RAF fighter pilot Andy Green intends to get behind the wheel of a car that is capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the Bloodhound car will mount an assault on the land speed record.

Wing Cmdr Green is writing a diary for the BBC News Website about his experiences working on the Bloodhound SSC (SuperSonic Car) project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

A 'BIBLE' FOR ENGINEERS

August is normally a really quiet month, where nothing happens because everyone is on holiday.

So why were we still so busy, with several commercial deals being discussed? I don't know, but it's a nice problem to have - we must be doing something right.

Last month, we did something unique in the history of the World Land Speed Record. We have published all the technical details of our car - before we've even built it.

The Vehicle Technical Specification, external is sort of a 43-page-long "genome of Bloodhound SSC": you could pretty much build one from this information, which is just what we're doing.

You won't find a motor racing team or aerospace company sharing this much information: they can't afford to.

This sort of access is unique to the land speed record - it's one of Bloodhound's greatest strengths. This information won't help our competitors much, as they are building radically different vehicles.

The V-shaped keel on the Bloodhound wheel

It will help our education programme, external, though. It gives students a real-time look at the "engineers bible" for building a 1,000 mph car, which we'll update as we go along.

Once again, Ron Ayers (our aerodynamics and performance guru) has come up with a brilliant observation. We have chosen a V-shaped keel profile for the wheels of the car and the aerodynamic analysis shows that these wheels will reduce the drag of the vehicle by several percent.

So what? We can already reach 1,000mph with our current drag estimates. But as Ron pointed out, if we have some drag "to spare", then we can use it to widen the rear-wheel track, increasing the roll-over stability of the car.

This further improves Bloodhound SSC's safety margins, so it gets my vote. Well done (again), Ron!

One of the most common questions about Bloodhound is "what about the G forces on the driver?, external"

Upside down - negative G to simulate Bloodhound SSC's acceleration

As the Royal Air Force's Chief Research Medical Officer Wing Commander Nic Green says: 'These effects are likely to be quite uncomfortable, physically tiring and potentially distracting'. As a Royal Air Force fighter pilot, it's nothing that I haven't seen before, but it's still something to think about.

It's also something that the team has been asking about.

So last month I invited them to come and try it for themselves in an Extra 300.

As a high-performance aerobatic aircraft, the Extra 300 can easily reproduce the -2.3G (acceleration) and +3.3G (deceleration) forces that I'll experience in Bloodhound SSC.

However, it's not a comfortable experience and a few of the team were feeling "a bit rough" afterwards.

Nic Green's description of "quite uncomfortable" doesn't really do it justice.

A fighter pilot's aeroplane: The Extra 300

After flying eight passengers in a row, I'd had enough as well! It was worth doing though - it gave eight of the team a chance to see what Bloodhound SSC's G forces will feel like, and it gave me the confidence that I could drive as many runs as we need. I'm feeling that bit more ready to drive now.

Out in South Africa, our track preparation efforts are continuing.

We are hugely fortunate to have the support of the Northern Cape Government - with 24 million square metres of track to clear, we need all the help that we can get.

We also need to make sure that we are fully compliant with the South African environmental legislation.

In 1997, the Thrust SSC team set the current World Land Speed Record in the Black Rock Desert, Nevada.

At the end of that year, the team was presented with an environmental award from the US Government, for leaving "cleaner than when we arrived". This is the standard that we must achieve again in South Africa.

I had no idea how we were going to approach this challenge, but our track boss, Rudi Riek, has found the perfect people to help.

Two South African companies, Terrasoil and EkoInfo, have been surveying Hakskeen Pan, external to check that a Land Speed Record attempt will not do any environmental damage.

While a formal environmental impact assessment will take six months, the initial indications are very positive - from an environmental perspective, South Africa's Northern Cape is the ideal place for the world's first 1,000mph race track.

- Published10 September 2010

- Published31 August 2010

- Published13 August 2010

- Published8 July 2010