Bloodhound diary: An F1 boost

- Published

RAF fighter pilot Andy Green intends to get behind the wheel of a car that is capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the Bloodhound car will mount an assault on the land speed record.

Wing Cmdr Green is writing a diary for the BBC News Website about his experiences working on the Bloodhound SSC (SuperSonic Car) project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

COSWORTH POWER COMES ON BOARD

Another Falcon Rocket test is due soon

The end of the year is getting closer and work continues flat-out to finish the chassis design, before manufacture starts in the New Year.

There is growing interest in the project from sponsors both here and abroad, and although things are a bit hand-to-mouth right now, major deals are now coming in. On Wednesday, we announced that F1 engine supplier Cosworth was coming on board, and we'll be signing up another great name in just a few weeks (I promised this back in August, but it really is close now!). These will help a lot.

We are still on track to have the car built by the end of next year and test-running on a runway in the UK in early 2012. Meanwhile, we are going to do a pressure-fed rocket test at full power in the near future, to prove the catalyst pack under maximum load.

The catalyst pack needs to cope with over 900 litres of HTP (concentrated hydrogen peroxide) being forced through it at over 1300 pounds per square inch (76 Bar). To produce this pressure and flow rate, the pump is driven at 11,000 revs per minute and needs up to 700 hp to turn it. That's where Cosworth come in. We've now got one of their latest F1 engine (yes, really) as our Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) just to turn it.

The T-tail may come down a bit, but there’s still room for your name on the fin

The evolution of the external shape continues, with a look at the T-tail configuration. Having the rear winglet right at the top is good for the aerodynamics, but not for structural rigidity, so we're looking at moving it half-way down the fin for extra strength. The aerodynamic testing is being done right now, so we can confirm this change soon.

Meanwhile, the Fin continues to fill up with names (the Union Flag is made up from thousands of names of our supporters) - now's the time to get your name on the fin, external before it's full!

Ron Ayers, our enduringly brilliant aerodynamics and performance expert, has developed a model of the V-shaped wheel interaction with the desert. His figures indicate that the drag will be much lower than our previous estimates, as the wheel "planes" on the surface at high speed, like a boat hull.

Is he right? I don't know - but history indicates that he usually is. The reduction in drag means that we can widen the rear-wheel track still further, from its original 1.8m out to 2.2m, increasing the car's stability by nearly a fifth - which gets my vote!

Another advantage of the V-shaped wheels is that they will be much more aerodynamic than the previous square-edged designs, external, which might allow us to reduce or even remove the rear wheel fairings. This will avoid any problems of damage from the huge vibration and heat from the jet and rocket.

The proposed V-shaped wheel – lower drag benefits stability and performance

October has seen some supply-chain successes. As well as our APU above, we've found a couple of possible suppliers for the carbon-carbon disc brakes that the car will use at "slow" speed - below 250mph. With new sources for the carbon discs, we've decided not to use a surface drag brake like the one used on the Craig Breedlove/Steve Fossett car.

By the way, the Fossett car is up for sale, so if they can find a buyer with a few million dollars, then we might have some 800+ mph competition by next year.

I really hope they do - it will make the race to 1,000 mph that much more exciting if there are other challengers for the Land Speed Record, external. Other cars to study and compare will also add another element to our education programme, external, which has now reached over 4,000 schools and colleges. If your school isn't studying Bloodhound science yet, now's the time to sign up!

I think we've also found our ideal chute supplier. After two years of looking, I went to talk to Survival Equipment Services. They've got everything that we need for both the runway testing and the high-speed running, and they are keen to help. Stopping the car is important (acceleration is optional as I can always throttle back, but when we hit 1,000 mph, slowing down becomes compulsory!).

Thrust SSC slowing down – Bloodhound will use similar chutes, supplied by SES

The airbrake design is also coming on. The problem with modelling airbrake airflow is that they create a lot of turbulence - in other words, the flow is unstable. This is a very complex problem for a computer and needs a huge amount of computing power. Hence we're running the problem on a computer called HECToR - one of the most powerful supercomputers in the UK (500 million million calculations per second). Answers to follow shortly...

Bloodhound has been out to meet the public, with our first visit to London. The exclusive bank Coutts hosted the show car in its front window on the Strand, generating great interest from passers-by and some fun photographs when we arrived.

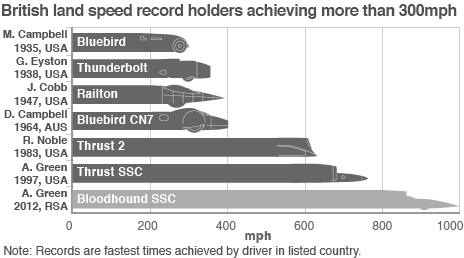

Bloodhound was also a major part of the Land Speed Record weekend at Coventry Transport Museum. Thrust 2 took the record from the Americans back in October 1983 and Thrust SSC broke that record (and the sound barrier) in October 1997 - so the UK has now held the record for a total of 27 years.

It was interesting to compare Bloodhound SSC with the current record holder, Thrust SSC, which set the current record with 763mph.

Bus, taxi, or 1,000mph?

Bloodhound SSC will have more power than Thrust SSC, but only half the weight and less than half the drag - which is why it's so much faster. From a standing start, Bloodhound will be stationary 10 miles away in 100 seconds. That's what I call performance.

The 10 miles in question is of course in the Northern Cape of South Africa. Great news from there also: we have now got all of the environmental clearances in place and can start work on the desert. Now there's just the small matter of clearing the 24 million square metres of desert surface that Bloodhound will need to run.

Our friends at the Northern Cape are fired up about creating the world's fastest race track - so a huge thank you to them in advance - and I'll tell you more about this epic piece of activity month.

- Published13 September 2010

- Published10 September 2010