Shuttle retirement ushers in new era

- Published

- comments

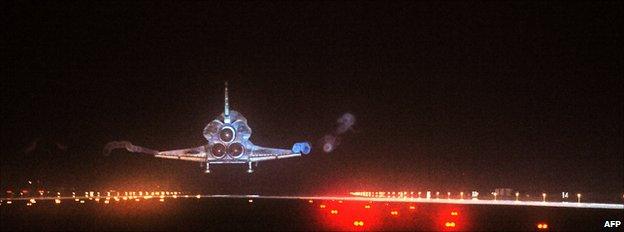

The cheers and the tears. The Atlantis shuttle returned from space on Thursday, book-ending the 135-flight sequence of Nasa's re-usable spaceplanes.

People will debate long and hard on the value of the shuttle. There's no denying its iconography; its story is inextricably linked with that of Hubble; and it gave us the space station.

And as Valerie Neal, the space history curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, points out in her assessment article for the BBC, the shuttle made possible "our continual, expanding presence in space".

The ISS has been occupied permanently now for more than 10 years. That would not have been possible, certainly on the scale we see today, were it not for those big orbiting trucks.

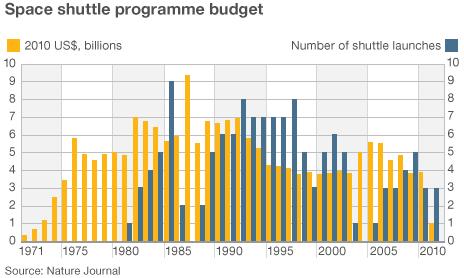

But there's also no denying the heavy cost, financially - $200bn from beginning to end, external seems to be the figure with most currency - and it was inevitable that some other, more affordable approach would have to be found.

Boeing's capsule will carry up to seven, but those astronauts need somewhere to go

Nasa is now inviting the private sector to take on the role of ferrying astronauts to and from the space station.

Just like a major corporation that contracts out its IT and payroll needs, so Nasa is going to contract out space transportation.

Instead of owing spacecraft, the US space agency will in future just buy the "taxi service".

Nasa hopes the commercial sector can find methods of operation that are substantially cheaper but, crucially, no less safe.

Already, four companies believe they have what it takes.

Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corporation, SpaceX and Blue Origin are working on a range of vehicles.

Most are "standard" capsules; one is a winged ship.

In part, what these companies are doing is going back to tried and tested ideas, but bringing them up to date.

Programme's end: The shuttle runway is marked where the main landing gear stopped

As Dr John Logsdon, professor emeritus of the Space Policy Institute at The George Washington University, says: "We're not asking industry to do anything cutting-edge here; what we're asking US industry to do is replicate the capabilities that were developed in the 1960s to do the relatively simple task of carrying a few people to orbit. That doesn't require new, or emerging or breakthrough technologies."

Private industry will deliver very capable machines. If you look at Boeing's proud history, there is every reason to expect its proposed CST-100 capsule, external to be top-notch.

The more interesting question may surround the viability or strength of the commercial market for space transportation that Nasa now seeks to establish.

If you speak to the contenders, they are very bullish about the prospects, of course. You'd expect that.

But it was interesting to hear a couple of weeks ago from the chairman of the Orbital Sciences Corporation, David Thompson, when he expressed the view that the level of demand over the next decade might support one, maybe two, commercial operators. That's all.

I remember talking to Bernardo Patti, Europe's International Space Station (ISS) manager, when we were at Kennedy in April.

I suggested to him that the European Space Agency could purchase regular seats for its astronauts on the new crew taxis when they came into service.

He shook his head: "Going to the ISS is simple; living there for six months is much more complicated. You need resources and the systems onboard are not really sized for more people.

"I can go to Mr Boeing, get a capsule, and knock on the door of the station, but you need the agreement of the Americans and the Russians to stay there. It's not just about having the plane ticket; you need the hotel room as well, and in a hotel which is already fully booked."

Into retirement: Atlantis is towed back to the Orbiter Processing Facility at the Kennedy Space Center

This is why the issue of destinations is going to become a hot topic in the next few years. For this emerging market to support more than one player, there needs to be more than one destination. That or a wider range of uses for these commercial space taxis.

It's no surprise therefore that Boeing, for example, has allied itself closely with hotel entrepreneur Bob Bigelow. He has been investigating the possibilities offered by inflatable space structures.

He's already flown test articles in orbit and plans to loft the first of several inflatable space stations around the middle of the decade.

Sensibly, the other would-be taxi services are shaping their operations so that they are not dependent solely on Nasa income.

SpaceX is looking to grab a sizeable share of the satellite launch market. The Sierra Nevada Corporation, which proposes to sell Nasa astronaut seats in its winged Dream Chaser vehicle, talks about the market for servicing satellites in orbit.

It will be fascinating to see how the "business" of human spaceflight evolves over the next few years, and the extent to which it is able to operate without overarching subsidies from government. We'll see.

Last word goes to the optimists and the commander of the last shuttle, Chris Ferguson: "Given everything that I know today, I think that we'll be traversing back and forth in low-Earth orbit with one of the four or five vehicles that are being considered right now," he told reporters on Thursday.

"I think that we're going to have people spending either short or perhaps long periods of time in orbit, who have paid for a trip there.

"You know, I don't think it's too much unlike the airlines. You recall the whole aviation industry got started with Naca, external. They designed aerofoils, they enabled aviation to take off. And Nasa, I think, has really laid the foundation for spaceflight, for commercial spaceflight to take off. So I think in 10 years, we'll see that."