Neanderthal sex boosted immunity in modern humans

- Published

Human leucocyte antigen (mauve) is expressed on the outside of white blood cells

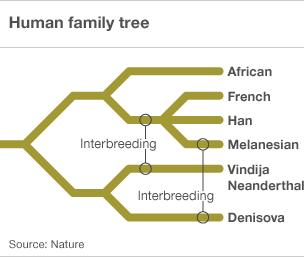

Sexual relations between ancient humans and their evolutionary cousins are critical for our modern immune systems, researchers report, external in Science journal.

Mating with Neanderthals and another ancient group called Denisovans introduced genes that help us cope with viruses to this day, they conclude.

Previous research had indicated that prehistoric interbreeding led to up to 4% of the modern human genome.

The new work identifies stretches of DNA derived from our distant relatives.

In the human immune system, the HLA (human leucocyte antigen) family of genes plays an important role in defending against foreign invaders such as viruses.

The authors say that the origins of some HLA class 1 genes are proof that our ancient relatives interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans for a period.

At least one variety of HLA gene occurs frequently in present day populations from West Asia, but is rare in Africans.

The researchers say that is because after ancient humans left Africa some 65,000 years ago, they started breeding with their more primitive relations in Europe, while those who stayed in Africa did not.

"The HLA genes that the Neanderthals and Denisovans had, had been adapted to life in Europe and Asia for several hundred thousand years, whereas the recent migrants from Africa wouldn't have had these genes," said study leader Peter Parham from Stanford University School of Medicine in California.

"So getting these genes by mating would have given an advantage to populations that acquired them."

When the team looked at a variant of HLA called HLA-B*73 found in modern humans, they found evidence that it came from cross-breeding with Denisovans.

Scanty remains

While Neanderthal remains have been found in many sites across Europe and Asia, Denisovans are known from only a finger and a tooth unearthed at a single site in Russia, though genetic evidence suggests they ranged further afield.

"Our analysis is all done from one individual, and what's remarkable is how informative that has been and how our data looking at these selected genes is very consistent and complementary with the whole genome-wide analysis that was previously published," said Professor Parham.

A similar scenario was found with HLA gene types in the Neanderthal genome.

"We are finding frequencies in Asia and Europe that are far greater than the whole genome estimates of archaic DNA in modern humans, which is 1-6%," said Professor Parham.

The scientists estimate that Europeans owe more than half their variants of one class of HLA gene to interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Asians owe up to 80%, and Papua New Guineans up to 95%.

Uneven exchange

Other scientists, while agreeing that humans and other ancients interbred, are less certain about the evidence of impacts on our immune system.

"I'm cautious about the conclusions because the HLA system is so variable in living people," commented John Hawks, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US.

DNA from a tooth (pictured) and a finger bone show the Denisovans were a distinct group

"It is difficult to align ancient genes in this part of the genome.

"Also, we don't know what the value of these genes really was, although we can hypothesise that they are related to the disease environment in some way."

While the genes we received might be helping us stay a step ahead of viruses to this day, the Neanderthals did not do so well out of their encounters with modern human ancestors, disappearing completely some 30,000 years ago.

Peter Parham suggested a parallel could be drawn between the events of this period and the European conquest of the Americas.

"Initially you have small bands of Europeans exploring, having a difficult time and making friends with the natives; but as they establish themselves, they become less friendly and more likely to take over their resources and eliminate them.

"Modern experiences reflect the past, and vice versa."

- Published22 December 2010