Space debris: Time to clean up the sky

- Published

- comments

Fortunately, there have been very few collisions in orbit so far

The US National Research Council's report on space debris, external is not the first of its kind.

A wide range of space agencies and intergovernmental organisations has taken a bite out of this issue down the years.

The opinion expressed is always the same: the problem is inescapable and it's getting worse. It's also true the tone of concern is being ratcheted up.

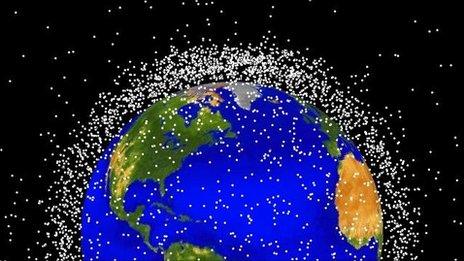

There is now a wild jungle of debris overhead - everything from old rocket stages that continue to loop around the Earth decades after they were launched, to the flecks of paint that have lifted off once shiny space vehicles and floated off into the distance.

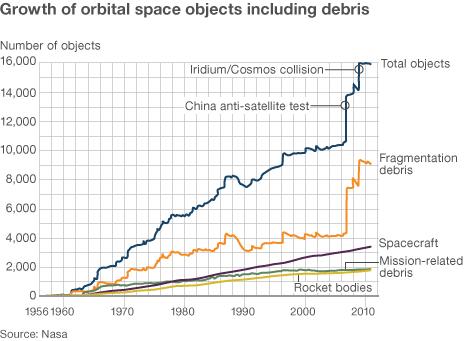

It is the legacy of more than half a century of space activity. Today, it is said there are more than 22,000 pieces of debris actively being tracked.

These are just the big, easy-to-see items, however. Moving around unseen are an estimated 500,000 particles ranging in size between 1-10cm across, and perhaps tens of millions of other particles smaller than 1cm.

All of this stuff is travelling at several kilometres per second - sufficient velocity for even the smallest fragment to become a damaging projectile if it strikes an operational space mission.

Gravity ensures that everything that goes up will eventually come back down, but the bath is currently being filled faster than the plug hole and the overflow pipe can empty it.

Man and nature are also conspiring in unexpected ways to make the situation worse. The extra CO2 pumped into the atmosphere down the years has cooled some of its highest reaches - the thermosphere.

This, combined with low levels of solar activity, have shrunk the atmosphere, limiting the amount of drag on orbital objects that ordinarily helps to pull debris from the sky. In other words, the junk is also staying up longer.

The German space agency's DEOS spacecraft could capture rogue satellites

Leaving aside the growth in debris from collisions for a moment, the number of satellites being sent into space is also increasing rapidly.

The satellite industry launched an average of 76 satellites per year over the past 10 years. In the coming decade, this activity is expected to grow by 50%.

The most recent Euroconsult analysis, external suggested some 1,145 satellites would be built for launch between 2011 and 2020.

A good part of this will be the deployment of communications constellations - broadband relays and sat phone systems.

These constellations, in the case of the second-generation Iridium network, can number more than 60 spacecraft.

By and large, everyone operating in orbit now follows international mitigation guidelines, external. Or tries to.

These include ensuring there is enough propellant at the end of a satellite's life so that it can be pushed into a graveyard orbit and the venting of fuel tanks on spent rocket stages so that they cannot explode (a major source of the debris now up there).

The goal is to make sure all low-orbiting material is removed within 25 years of launch.

I say "by and large" because there has been some crass behaviour in the recent past. What the Chinese were thinking when they deliberately destroyed one of their polar orbiting satellites, external in 2007 with a missile is anyone's guess. It certainly defied all logic for a nation that professes to have major ambitions in space.

The destruction created more than 3,000 trackable objects and an estimated 150,000 debris particles larger than 1cm.

It was without question the biggest single debris-generating event in the space age. It was estimated to have increased the known existing orbital debris population at that time by more than 15%.

A couple of years later, of course, we saw the accidental collision of the Cosmos 2251 and Iridium 33 satellites, external. Taken together, the two events essentially negated all the mitigation gains that had been made over the previous 20 years to reduce junk production from spent rocket explosions.

There are lots of ideas out there to clean up space. Many of them, I have to say, look far-fetched and utterly impractical.

Uncertain future

Ideas such as deploying large nets to catch debris or firing harpoons into old satellites to drag them back to Earth are non-starters. If nothing else, some of these devices risk creating more debris than they would remove.

It has been calculated that just taking away a few key spent rocket stages or broken satellites would substantially reduce the potential for collision and cap the growth in space debris over coming decades. And in the next few years we're likely to see a number of robotic spacecraft demonstrate the rendezvous and capture technologies that would be needed in these selective culls.

The German space agency, for example, is working on such a mission called DEOS, external that is likely to fly in 2015.

Dr Robert Massey, Royal Astronomical Society: "It is a serious issue"

These approaches are quite complex, however, and therefore expensive. Reliable low-tech solutions will also be needed.

There is a lot of research currently going into deployable sails, external. These large-area structures would be carried by satellites and rocket stages and unfurled at the end of their missions. The sails would increase the drag on the spacecraft, pulling them out of the sky faster. Somehow attaching these sails to objects already in space is one solution that is sure to be tried.

"There are a number of technologies being talked about to address the debris issue - both from past space activity and from future missions," says Dr Hugh Lewis, a lecturer in aerospace engineering at Southampton University, UK.

"I think we are a long way off from having something which is reliable, relatively risk-free and relatively low cost.

"There are number of outstanding and fundamental issues that we still have to resolve. Which are the objects we have to target and how many do we remove? Who's going to pay?

"It is also worth remembering there are a lot of uncertainties in our future predictions. Reports that you read typically present average results; we tend to do ensembles in our simulations and some outcomes are worse than others. So, many issues still need to be addressed, but that dialogue is taking place.

"This report paints quite an alarming picture but I think we can be a bit more upbeat, certainly if we are contemplating removing objects.

"Fortunately, space is big and collisions are still very rare. After all, we've only had four known collisions and only one involving two intact objects. It's still not a catastrophic situation, and we need to be careful about using phrases like 'tipping point' and 'exponential growth'."

- Published9 August 2011

- Published2 September 2011