'Hollows' mark Mercury's surface

- Published

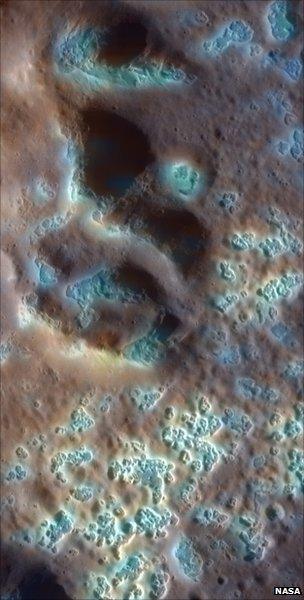

Messenger has found swathes of shallow, rimless depressions on the surface

Hands up who thought Mercury was just a dull rock circling close to the Sun?

The latest data returned by Nasa's Messenger probe shows that view couldn't be further from the truth.

In among a raft of papers published in this week's edition of the journal Science, researchers reveal strange hollows that pock Mercury's surface.

Irregular in shape, these depressions seem to form in the bright deposits that have been excavated where meteorites have impacted the surface.

The Messenger team cannot be sure what has caused them, but on Mars similar features are also known to exist.

In the case of the Red Planet, they are probably a consequence of evaporating carbon dioxide ice.

As the ice is driven off in the warmth of the Sun, it leaves a hole in the ground that produces a kind "Swiss cheese" terrain.

On Mercury, there is no carbon dioxide ice, so it would have to be some other kind of volatile material in play.

"It could be that there is some component in Mercury rocks that is unstable when it is exposed to the environment at the surface," said David Blewett of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

"As a result of this instability, portions of the surface could degrade, leading to collapse and erosion and thus forming the depressions."

Clues to what those materials might be come from Messenger's X-ray and gamma-ray spectrometers.

These instruments are detecting relatively high abundances of elements such as sulphur and potassium in surface materials.

If they are present, other elements which do not particularly like high temperatures are probably there as well.

All of which poses new questions about the formation of Mercury.

There have been several models put forward to try to explain why the planet has an unusually large iron core.

Some scientists have argued that the planet must have been bigger in the past and that its outer-layers had simply evaporated away in the intense glare of the Sun; or that a number of giant impacts had stripped Mercury of its outer layers.

"But those [models] propose such high temperatures that all the volatiles would have been evaporated away, so they don't line up with our measurements of the potassium and sulphur abundances," said APL's Patrick Peplowski.

"The exciting thing about our observation of volatiles at the surface of Mercury is that it rules out most theories for the planet's formation."

Peplowski now favours a model in which Mercury accreted a lot of metal-rich meteorites early in its evolution.

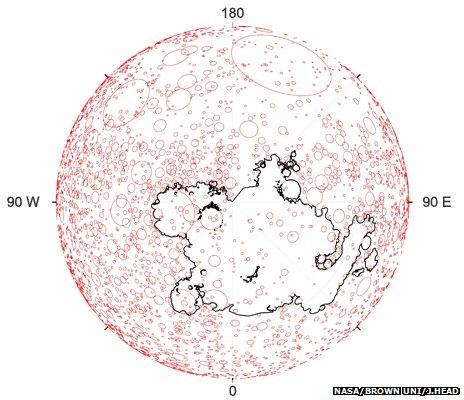

One aspect of Mercury is now settled, however - the scale of the volcanism that built its smooth northern plains.

Before Messenger got into orbit, there had been only brief glimpses of the region which covers more than 6% of the planet's surface.

Now, high-resolution mapping has identified buried "ghost" craters that were overwhelmed by the floods of molten rock welling up from inside Mercury.

Some craters on the plains were just about covered over by the lava to leave a ghost-like impression

"Taking the 6% area of Mercury covered by these northern high latitude smooth plains, and an estimated average depth of one kilometre, gives us a volume of almost 5 million cubic kilometres of lava for these deposits," said James Head, from Brown University.

"This is enough lava to cover the City of Washington DC to a depth of over 26,000 km, which is about 72 times higher than the orbit of the International Space Station."

There are no volcanoes visible in the imagery, but Professor Head and his colleagues have identified huge vents just off the plains that might explain how all the lava came to be released.

"It looks like there was a large low in the northern high latitudes that when the lava came out, it just filled the low up like a bathtub," he told BBC News.

Messenger is half way through its primary orbital mission at Mercury, and has another six months of observations to make before it would require additional funding to extend operations.

The request for an extended mission has already been put before Nasa officials and, given the results coming back from the probe, it is hard to believe that request would be turned down.

"Ten years ago you might have thought Mercury was a boring place. Now we're getting all this data from Messenger, the planet has become a truly fascinating place," said David Rothery, an Open University-based British scientist working on Europe's soon-to-launch Mercury mission, BepiColombo.

Looking down on the north pole, the extent of the plains is apparent (within black line). The area is roughly equivalent to 60% of the continental US

- Published16 June 2011

- Published18 March 2011

- Published15 July 2010