Russia asked to join ExoMars project

- Published

The 2016 orbiter would look for trace gases like methane in the atmosphere of Mars

Europe has formally invited Russia to participate in space missions to Mars in 2016 and 2018.

A "yes" from the Russian space agency (Roscosmos) may be the only way of saving the missions which are at risk of cancellation due to lack of funds.

The 2016 mission involves a satellite to study the Martian atmosphere, while a big robot rover to investigate the surface is scheduled for 2018.

Both are being planned with the US, which is also struggling financially.

If Russia can be persuaded to provide a rocket to launch the 2016 satellite, it should make both atmospheric and surface ventures financially feasible.

But the European and US space agencies (Esa and Nasa) know that for Roscosmos to be interested, it will want a meaningful degree of participation.

The in-kind return for Russia would be the opportunity to provide instrumentation and technology for the missions, and for its researchers to be included in the science teams.

If Russia could bring a Proton rocket to the project, it would become financially more feasible

Esa, Nasa and Roscosmos have set themselves a deadline of January to see if there is a way all parties can be satisfied.

"Everything is open for discussion," said Esa director of science, Alvaro Gimenez.

"There are possibilities for the Russians to contribute to the rover; there may also be possibilities for them to contribute to the payload on the orbiter," he told BBC News.

"Of course, in the case of 2016, we don't have much time available to get everything on board; and in the case of 2018, we don't have much room available because it is just a single Esa/Nasa rover.

"That's why we have to start the discussions now, to see what the Russians have available and what they can develop in a fast-track."

Esa's and Nasa's joint Mars programme (known in Europe as ExoMars) has looked increasingly unsteady in recent months.

The US let it be known during the summer that it could no longer afford to provide the rocket to launch the 2016 orbiter; and Europe, which still has not raised the full funds needed for ExoMars among its member states, has no money available to buy a rocket itself.

The hope is that by bringing Roscosmos into the programme, Russia could supply one of its Proton launch vehicles to send the satellite on its way.

Seeking a return

Quite where Russia would see its return in the missions is unclear at this stage.

The 2016 orbiter has passed its design review, and its primary instrument opportunities have all been allocated to scientific teams in the US and Europe.

Italian industry has already begun the process of building the satellite, albeit at a slow pace because of the uncertainties surrounding ExoMars and its final architecture.

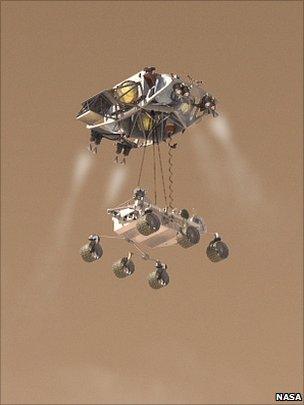

Esa and Nasa plan to land a rover on Mars in 2018 - but is there room for Russia?

But the window for participation even on the satellite is not completely closed yet, European officials insist.

On the other hand, the 2018 rover is not so well defined as the satellite, and so Roscosmos may find there are more technical and scientific options to participate in the surface mission.

Discussions cannot be allowed to drag on too long. Industry has already warned that it faces a tight schedule to get the 2016 satellite ready for launch.

If no deal is done with Russia by February, Esa and Nasa may be forced to abandon the satellite project and just concentrate on the rover mission.

This is not as simple as it sounds - certainly in Europe, where space missions are carefully put together as shared packages of work. Unpicking the ExoMars programme risks upsetting certain Esa member states that have a greater interest and a bigger investment in the first part of the programme.

Cancelling 2016 also throws up a rather more fundamental technical problem for 2018, in that the satellite is supposed to act as the telecommunications relay to get all the rover's data back to Earth.

A dedicated telecommunications orbiter would therefore have to be included in any revised 2018 mission.

"For us of course, 2018 is the core of ExoMars," Dr Gimenez told BBC News.

"The ExoMars programme started as a rover; it's whole history has been about the rover. We then had to reconfigure the mission in recent years, but it was still all about the rover in 2018.

"It would be difficult to call it ExoMars if there was no rover," he said.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk

- Published20 September 2011

- Published5 September 2011

- Published30 June 2011

- Published8 March 2011