Nasa science chief 'fighting' for planetary research

- Published

John Grunsfeld took over the science chief post in January

Nasa's science chief has told planetary scientists he is "in there fighting for you" after the swingeing cuts proposed to the robotic exploration budget.

Former astronaut John Grunsfeld was speaking at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Texas.

He faced hundreds of researchers at a special session to explain the 21% cut to planetary science in President Obama's latest budget request for Nasa.

The decision forced the agency to pull out of joint Mars missions with Europe.

Mr Grunsfeld took over as science chief on 4 January this year, after the key budgetary decisions had already been made. He has previously admitted he was disappointed when he learned of the proposals for planetary science.

"The Nasa budget was really the result of some tough choices and national priorities," he told his audience.

"The fact that the Nasa's planetary budget took such a great hit was one of those tough priority settings," and added: "It was a strategic decision."

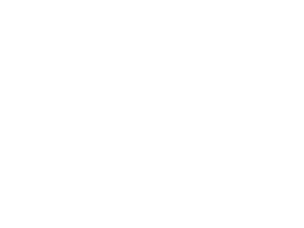

Where the James Webb telescope has benefited, planetary science has lost out

The planetary exploration budget funds robotic missions to other bodies in the Solar System, such as Mars, the Moon and the outer planets.

The proposal for the Financial Year 2013 reduced the planetary science budget from $1.5bn to $1.2bn. The cuts would, in the words of one scientist, plunge the field into its biggest crisis since the 1980s and is considered likely to lead to the loss of up to 2,000 hi-tech jobs.

Although planetary science was a loser in general, Mars exploration was singled out for particular cuts, receiving $360.8m, which amounts to a reduction of almost 40% from the FY2012 estimate.

This kind of funding drop precludes Nasa from starting new missions in this part of its portfolio.

After the speech, Mr Grunsfeld fielded a question from Jim Bell, a planetary scientist and current president of the Planetary Society, a space advocacy organisation in California.

Prof Bell, who was one of the lead investigators on the Mars rovers mission, implored Mr Grunsfeld and Nasa's director of planetary science Jim Green to "fight back" against the plans, even if "you lose your jobs" because, he said, "it's the right thing to do".

In response, Mr Grunsfeld recalled a time in 2004 when he had considered resigning from Nasa's astronaut corps over a decision not to save the Hubble Space Telescope (HST).

He said: "History repeats itself… I decided on 4 January not to flee - I'm in there fighting for you."

'Weak' community?

Dr Mark Sykes, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, pressed Mr Grunsfeld on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The mission comes under a different budget at Nasa and represents the agency's successor to the HST. But it has already been delayed by several years and costs have ballooned by about $1.5bn.

Dr Sykes asked: "JWST went from $519m to $628m… it was about $100m that was contributed by the planetary science division to JWST. Is there a rationale for that level of contribution?"

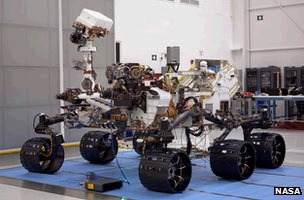

The Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity rover) could be the last surface mission for a while

Mr Grunsfeld replied that it was not a valuable exercise to try to "trace the dollars" and that if different divisions of science at Nasa were to fight, "we all lose".

After the session Dr Sykes told me: "Budgets are a conservative process and if you have a flat pot of money and something goes up and something comes down… it's a conservative process."

He added: "There is a little question about what's the motivation, or the policy underpinning that - who knows?"

But at a community forum at the LPSC on Tuesday, scientist and author Andy Chaikin said the cuts had occurred because "the planetary community is seen in some circles as being weak".

He added that the plans would be "starving the pipeline that sustains education and research in planetary science".

Spreading the pain

Mr Grunsfeld said that it would have been a mistake to spread cuts equally across Nasa's science portfolio: "The one way you can make sure that Nasa's dollars are less efficient is to take operating missions and those in development and say, 'you were going to launch in 2016, but now you can't go until '17 or '18.

"For the agency that means it's going to cost $200-$300m more. Planetary science happened to be in a place where we had just launched [Mars Science Laboratory], we had just launched [the Juno mission to Jupiter] and they could take the hit and not create a situation where there was a mission well through development that was going to get cut and it would have cost hundreds of millions more."

However, one researcher told me: "That's like saying things are coming to an end."

Many scientists are angry that the proposals ride roughshod over the results of the Planetary Decadal Survey, which laid out a vision for future exploration based on the priorities of the planetary science community.

This identified the goal of returning samples from Mars as a science priority. Joining Europe on its ExoMars programme, which aims to send landers to Mars in 2016 and 2018, would have led down that road.

However, some at Nasa had been reluctant to commit to so many costly "flagship" missions with a foreign agency, and have now got their wish.

The FY2013 budget proposal shifts funds to human spaceflight and space technology, in line with the agency's major commitments going forward to fund the development of a huge new rocket and capsule system to take astronauts beyond low-Earth orbit to destinations such as the Moon and asteroids.

But at the community forum session here at the LPSC, Dr Laurie Leshin from Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center, said that it made no sense for Nasa to cut the scientists who were vital for supporting such missions, including allowing them to land safely at their destinations.

At the event, Prof Steve Squyres, who chaired the Planetary Decadal Survey, said the community had to put on a united front in order to fight the plans, not as scientists who studied Mars or outer planets, "but as space scientists".

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published15 March 2012

- Published14 February 2012

- Published13 February 2012

- Published6 February 2012

- Published14 September 2011

- Published19 April 2011