UK industry to build Solar Orbiter satellite

- Published

Ralph Cordey from Astrium UK explains how the craft will be built to survive its mission to the Sun

British industry will lead the production of Solar Orbiter (SolO), a spacecraft that will travel closer to the Sun than any satellite to date.

SolO will take pictures and measurements from inside the orbit of Mercury, to gain new insights on what drives the star's dynamic behaviour.

The European Space Agency has signed a contract with Astrium UK to build the satellite, for a launch in 2017.

The deal is worth 300m euros (£245m), and the work will be done in Stevenage.

Dr Lucie Green: "The closest manmade object to the Sun"

With an eye on history, the contract signatures on the legal paperwork were timed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of UK activity in orbit.

It was 26 April 1962 that Britain became a space-faring nation, with the launch of the Ariel-1 satellite.

Esa director Alvaro Gimenez and Astrium executive Miranda Mills shook hands on the SolO project in London's Science Museum, where a model of <link> <caption>Ariel-1 is on display</caption> <url href="http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/visitmuseum/galleries/ariel_1.aspx" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

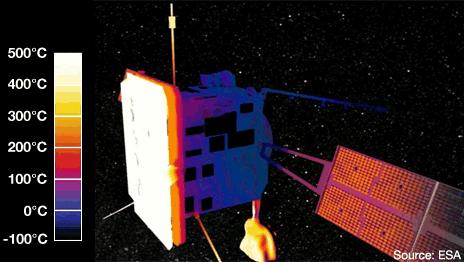

After launch, Solar Orbiter will take itself deep into the inner Solar System, flying as close as 42 million km from the Sun. This close proximity will require the spacecraft to carry a robust shield.

"Heat will be a huge problem," says Dr Ralph Cordey, the head of science at Astrium UK.

"If it were not protected, the face of the spacecraft would get as hot as 500 degrees - which would be disastrous.

"We will use a thick heatshield to reduce the temperature within the spacecraft and its systems down to about room temperature so that all the electronics can operate comfortably."

Solar Orbiter will need to be protected by a multi-layered heatshield

SolO's remote sensing instruments - its imagers and telescopes - will look though slots which have shutters that can be closed when no observations are being made.

The mission is designed to enhance our understanding of how the Sun influences its environment, and in particular how it generates and accelerates the flow of charged particles in which the planets are bathed.

The contract signing with Astrium UK was done at the Science Museum in London

This solar wind can be very turbulent, and big eruptions on the solar surface will create major perturbations in the wind. When this stream of particles hits the atmosphere at Earth and the other planets, it triggers spectacular auroral lights.

"Solar Orbiter's mission will tell us how the Sun creates the heliosphere, which you can think of as its atmosphere," explained solar physicist Dr Lucie Green from University College London.

"The heliosphere is hot and it expands out into space for about 17 billion km.

"We don't really know how it's formed and how it varies with time, but Solar Orbiter will get really deep into that atmosphere to see where on the surface the emissions are coming from, to ultimately understand how the great bubble is made."

To sample the solar wind as it comes off the surface, Solar Orbiter has five in-situ instruments.

The probe's orbit will also take it high above the plane of the planets so it can see some of the processes at play on the Sun poles. And the speed of SolO around the star means it will be able to follow events and features that would normally rotate out of view of Earth-based observatories.

More missions

At the heart of the endeavour is a desire to understand better the causes of what solar physicists call "space weather".

Big storms on the Sun that hurl billions of tonnes of charged particles out into space can disturb electromagnetic fields on Earth, resulting in communications interference and, in extreme cases, damage to power lines and satellite electronics.

Scientists would like to be able to forecast such events earlier and with more confidence.

Solar Orbiter is a joint venture between Esa and the US space agency (Nasa). The latter will supply one instrument, a sensor and the rocket to send the satellite on its way.

The project emerged from a competition among European space scientists to find the most compelling medium-class mission to take an available launch slot at the end of the decade.

Esa will soon sign off a second such mission, called Euclid, which will investigate the mysterious phenomena known as dark energy and dark matter, which appear dominate and shape the Universe we see through telescopes.

The first in a new class of large missions (those costing a billion euros or more) will be selected next week. This is expected to be a mission to study the icy moons of Jupiter.

The UK Space Agency is planning a year of celebrations to mark the British space sector's golden anniversary.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on <link> <caption>Twitter</caption> <url href="https://twitter.com/#!/BBCAmos" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published19 April 2012

- Published18 April 2012

- Published12 March 2012

- Published5 October 2011

- Published4 October 2011