Turbulence ahead: Flight heads into storm's heart

- Published

- comments

The BBC's David Shukman was on board the research flight

Scientists have flown into the heart of a turbulent weather system in a bid to uncover the causes of heavy rainfall.

A research flight off Southwest England gathered vital details about temperatures and water movements inside a band of cloud.

Coming amid weeks of wet conditions, the mission should help improve the forecasting of storms and flooding.

The flight criss-crossed a massive warm front edging across the English Channel towards the coast of Cornwall.

In a warm front, a mass of relatively warm air pushes against a block of cooler air and is forced to flow up over it.

The action of warm air rising rapidly through the atmosphere is usually a trigger for sustained, sometimes violent, rainfall.

The basic mechanisms at work have been known for decades but the so-called "micro-physics" are poorly understood.

Often the most damaging impacts of extreme weather come from relatively small features gaining strength within a larger system.

A BBC News team was on board for the flight which took off from Cranfield airport near Milton Keynes, headed over Wales and the Irish Sea and then south over the western approaches to the Channel.

Key facts

The project's chief scientist, Prof Geraint Vaughan of the University of Manchester, explained that entering a weather system is the only way to collect the key facts.

"This is one of a series of flights we've been doing over the past six months to look at storms of this kind, and what we're trying to focus on is small scale processes that we don't capture properly in the weather forecasting models at the moment."

Prof Vaughan's team is focusing on processes not captured by weather forecasting models

"The instruments we carry give us details of water droplets and ice particles we can't get any other way - these are very important for understanding the way a storm evolves."

I asked why it was so difficult to forecast the precise course of the events in a storm.

"It's because of a long chain of things that have to happen from the large scale of big weather systems you see on satellite images down to the fronts we're looking at today, and all the way down to the formation of raindrops.

"There's a long chain of processes in that and the details are quite subtle."

The warm front was crossed at high altitude in the region of the Scilly Isles. Everyone had to be strapped into their seats but in the event the ride was far less bumpy than expected.

The on-board instruments measured everything from temperature to pressure to the size and density of dust and ice particles in the clouds, the researchers gathering streams of information which will later be fed into computer weather models.

Clearer picture

As we approached and crossed the front, a series of "dropsondes" was ejected, devices which measure data about the atmosphere - and transmit it by radio - as they descend on parachutes.

The team regularly makes flights into the biggest storms around the UK

These provide a "vertical profile" of the weather conditions and offer a clear picture of the patterns of air and moisture within the system.

While majorstorms are easily tracked on radar - and their future paths can be relatively accurately predicted - their internal mechanics have eluded researchers until now.

One focus is on the so-called phase changes of water within a storm - evaporating from the ocean, rising as vapour, then cooling and forming ice or snow crystals and finally descending as rain.

Tracking the exact moments of transformation, and the resulting releases of heat at particular stages in the cycle, should help create a more accurate picture of when rain falls and why.

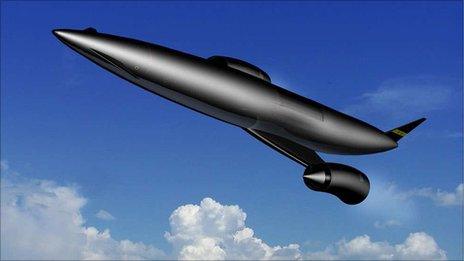

The aircraft, a BAe 146, is a converted passenger plane, with most of the seats removed to make way for a dozen consoles. It is operated by a publicly-funded organisation called FAAM working to the Met Office and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

The flight is one of a series run under a project known as DIAMET, funded by Nerc, which involves a consortium of UK universities and the Met Office.

- Published27 April 2012

- Published24 May 2011

- Published24 May 2011

- Published31 January 2011