What would Ernest Shackleton have tweeted?

- Published

The Antarctic remains a harsh and inhospitable place to work and live, but modern times has seen a tremendous influx of those who "overwinter", able to brave the conditions with just a few home comforts. The Antarctic-based doctor Alexander Kumar, originally from Derbyshire, UK, considers what email and social media have done to bring warmth to the icy conditions.

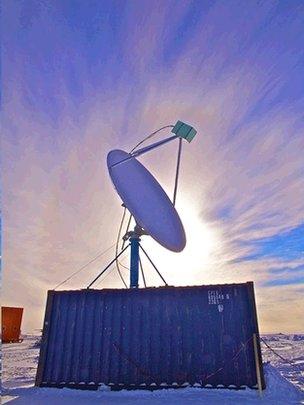

Shackleton's crew lacked satellite phones or email, but there are down sides to being plugged in

Nearly 100 years ago, Sir Ernest Shackleton's arm had been twisted and after some struggle he had been finally forced to announce to his crew to "abandon ship". His vessel, the Endurance, had been sealed in, crushed and eventually sunk by the unforgiving Antarctic ice, as his helpless and homeless crew looked on unable to save their trusted link back to civilisation.

I am a British medical doctor currently living and overwintering in Antarctica within a European crew of 12 others isolated and alone at Concordia, a French-Italian Research Station and one of the most remote human outposts, located in "middle Antarctic nowhere" within the most extreme environment on Earth.

As I walk outside under a starry, polar night sky, I wonder what Shackleton would have tweeted or how he would have updated his Facebook status: "Shackleton is.... sunk... Help!" perhaps, had his own expedition been able to communicate with the world they had left behind.

In February, some of this year's overwintering crew stood alone, waving goodbye to the last plane as it took off into the sunrise. It will not be until November that the next plane will arrive, if it does so at all.

I will never forget the moment, as I stood among the group, waving, I snapped this photo and remembered thinking how this is the closest anyone can come to feeling the same way as members of Shackleton's crew had who remained behind on Elephant Island.

They were isolated and marooned on the shoreline, waving off the James Caird boat, their very last hope and link to civilisation as it disappeared off into the horizon, not knowing if anyone would ever return and if they themselves would ever meet civilisation again.

Here we are living 100 years later in Antarctica, under a similar cloud of uncertainty, laying in wait for our return link back to civilisation. Like the men left on Elephant Island, we remain similarly physically unreachable but surprisingly not so uncontactable.

Bonding exercise

Having endured the imprisonment of the ice, Shackleton eventually escaped his certain fate and upon reaching his goal, he famously entered the Whaling Station Master's office on South Georgia. Bewildered, exhausted and unrecognisable to his former self, he summoned the strength to ask one of his own questions. He had asked the station master if the (First World) War had ended, unaware of its cataclysmic continuation.

His crew had been "alone" on the ice from 1915-16, unable to communicate with the outside world. But in being isolated, they had survived, becoming a stronger team than ever, immersing themselves in whatever theatricals and other forms of basic entertainment they could muster. They got to know each other like a family and supported each other. There was no other way.

Since Shackleton's expedition, a technological revolution in modern communications, have brought wide satellite phone coverage and increased internet capabilities. This has benefited many communities living in isolation all over the world, from Nome, Alaska, to overwintering manned research outposts such as Concordia in Antarctica.

As a current overwintering, lone station doctor, since reading the interesting cases in Antarctica's long and adventurous medical history including Russian Doctor Rogozov's famous surgical removal of his own infected appendix, I am always grateful to be able to discuss difficult or challenging medical cases live from Antarctica, with specialists back in Europe, via telemedicine.

Overwintering teams undergo sensory deprivation amid the bleak Antarctic environment

Today overwintering teams around the frozen continent, although being physically isolated, very much enjoy remaining being "plugged in" and connected to the world. We can send research data, follow civil wars, satisfy our curiosity confirming England's early and predictable exit from the Euro 2012 football competition and receive updates from loved ones.

I myself enjoy receiving photos of my Siberian Husky puppy who I left at home aged just 3 months. She is now fully grown and it has been interesting using her growth as a way to gauge my time away from home.

However, I would argue that such luxury in communication brings great potential risk to your well-being when overwintering in Antarctica.

Always a downside

Whilst overwintering, like Shackleton's crew, over the past months, I have found our team to have grown together with humour and stories of past experiences. A natural response in any overwintering team is to develop the view that other distant people are considered as such - as "others" and more so "outsiders".

They are separate and unable to truly understand the stresses of confinement, isolation and sensory deprivation experienced in overwintering, without doing so themselves.

I have also come to realise that the majority of problems that arise between crew members during winter on Antarctic bases, are so often not directly caused by internal base problems but in fact are "airdropped" in over the long, dark polar night by email, Facebook, Twitter, Telephone, video call, text or any other form of social media. Like precision missiles, they seek a target and explode, causing maximum damage, only in the vicinity of the base. Each team is left to clear up the aftermath.

Luxuries in communication bring great potential risks to well-being, says Alex Kumar

The potential for disaster always looms and statistically will always happen, if only because of the sheer number of people overwintering in Antarctica these days. It is not a question whether bad news will arrive, but instead is only a question of when it will do so and to whom.

So far we have been very fortunate in this respect. I will always remember one exception - an anonymous crew member who was dumped by their partner whilst out on the ice, on Christmas Day nonetheless. Fortunately, since we live in the coldest place on Earth with temperatures below -70C, we can make our own homemade ice cream on the base.

Living at Concordia, in a period of nine months of complete isolation from February through November, should a bomb of bad news be dropped, you are absolutely helpless to do anything and are unable to leave to attend to matters back home.

Things were very different 30 years ago within the British Antarctic Survey for example. Dr Chris Johnson, a friend and consultant anaesthetist who was overwintering at the British Antarctic Survey's Halley Station in the late 1970s, reminded me in an email about his own experience on the ice.

He explained to me how news from home only ever arrived in the form of an occasional, perhaps monthly 200-word Telex, containing a paragraph of text. In case of a problem, there was an excellent liaison officer who could assist greatly by communicating with the overwinterer and their family, in the event of stress, illness or bereavement.

When team members step outside, they emerge into one of Earth's most extreme environments

Today, our crew lives in a comfortable, modern Antarctic station, a century on from where Scott passed away in his tent, Shackleton's boat sank and Byrd sobbed into his folded frozen arms alone. Here, even with our limited internet access, we can sometimes access Facebook, Twitter and receive texts, and even video and telephone calls.

But we live in fear, like other wintering stations, addicted to our previous comparatively heavily-complicated lives, whilst playing a game of Russian Roulette with our computers. Every time we hit the get mail button, we rejoin civilisation, but never know when or by what means or whom will be struck first by such a bomb airdropped directly into our inboxes.

Tomorrow I will make my once monthly satellite phone call to my friend Dr Dale Molé, currently overwintering as the lone physician at the United States Amundsen Scott South Pole station. Usually we are both relieved to share Shackleton's exchange of words to his mate, Frank Wild, when he arrived back to rescue his marooned crew from Elephant Island, shouting "Are you all well", hearing Wild's reply, "All safe, all well", to which Shackleton responded, "Thank God".

After updating my blog, external, I pause as I realise again that just leaves me to connect to my email to send this article back to civilisation, from the most isolated and remote place on the planet. I press send and gulp as a message pops up, "You have mail". It seems social media itself has become one of the 21st century challenges to living happily and peacefully, on an edge, down here in the world's most extreme, remote and beautiful, yet connected environment. It could just be that in the Antarctic winter, no news is better than bad news.

Dr Alexander Kumar FRGS is the Concordia Station doctor (Institut Polaire Français) and European Space Agency-sponsored research MD

- Published31 March 2012

- Published29 March 2012

- Published17 January 2012

- Published10 March 2012