When 'state of the art' is also years old

- Published

- comments

The final MHS model will likely be 17 before it gets to do the job for which it was designed

It's possible to be brand new and old at the same time. That's the peculiarity of weather satellites and the way they're procured.

Because of the billions it costs to develop these special space systems, they're purchased in batches. The satellites then sit in storage until they're needed.

It means that newly launched spacecraft can in fact contain equipment which was delivered from the manufacturer years earlier.

This is the case with Europe's latest meteorological platform - Metop-B. It is the second in a three-satellite series and has just gone into orbit on a Soyuz rocket, external.

The first satellite, Metop-A, was launched back in 2006. The third platform, Metop-C, probably won't go up until about 2018. But all three of these spacecraft are circa early 2000s, and the industrial contracts that brought them into being were circa early 1990s.

So you have to wonder - how can anything that "old" deliver any sort of service that can be described as "new"?

It was a puzzle on my mind when I went to see one of the main British contributions to the Metop programme.

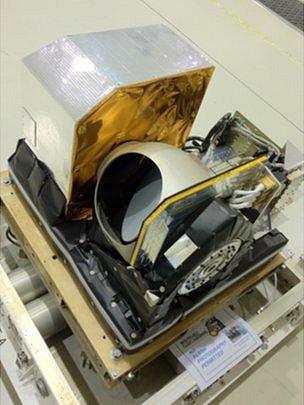

This is the Microwave Humidity Sounder (MHS), external, one of the eight meteorological instruments carried on each of the three identical Metop satellites.

UK engineers built these washing machine-sized objects to measure the water content sitting at different altitudes, including atmospheric ice, cloud cover and precipitation (rain, snow, hail and sleet).

It is fundamental information needed by the computer models to produce our daily forecasts.

The MHS batch model I saw will go up on that final 2018 Metop-C, a full 17 years after the instrument came off the "production line".

When you lay eyes on this remaining sounder, you immediately recognise its age. A little plate screwed to the side of the instrument announces the name of the manufacturer - Matra-Marconi Space, external. It is a famous name that no longer exists, subsumed years ago into the pan-European aerospace giant Astrium.

But, insists project manager Ian Stewart, "MHS was state of the art in '93, and it's state of the art today".

Brett Candy: "MHS data is critical for good weather forecasting"

He keeps an eye on things. Every year, he pulls the model out of its storage container to check everything is in good working order. If anything is playing up, it can be exchanged easily.

"We've built a lot of pre-assembled units in there. It's not quite plug and play, but it's as good as that. We don't have to go and de-wire boards - we have a replacement unit that we can just slot in."

The immense cost of these systems means it is impractical to buy a new version for every launch

But even if the hardware looks a bit quaint by today's standards, what about the science it can do? It's tip-top, maintains the UK Met Office; and like all the Metop instruments, MHS continues to stretch the models and the forecasters

"We're still in the situation where the data from this instrument is the topic of research," explains Nigel Atkinson, an expert scientist in satellite applications at the Met Office.

"Some of the data from the standard humidity channels, we know how to handle; and then there's the precipitation-affected channels that are a new area. So, we can exploit this data and improve weather models. We're not sitting there saying 'this is an obsolete instrument' - it is still something which can push forecasts forward."

In other words, the data MHS acquires is made to work harder and harder as the science of meteorology advances.

In this pre-launch image of Metop-B, MHS is the big silver box two-thirds of the way up the satellite

Studies have compared all the different types of observations (including surface weather stations, balloons and aeroplanes, etc) ingested in weather models and found that Metop data makes the largest contribution to the accuracy of 24-hour lookahead, at around 25%.

Is is a big impact. Consider for a moment all the lives that have been saved and all the damage to property that has been prevented by Metop-supported weather forecasts. The value of those forecasts must equate to hundreds of millions of pounds every year across Europe.

Inevitably, though, the time comes when one must move to next-generation instruments. That is the discussion taking place right now, although the cost of a new and improved Metop system means the future satellites and their instruments will again be a batch-buy. The figure being quoted is just shy of 3bn euros for a series of spacecraft that would likely operate in the 2020s and 2030s.

The cost will fall on nations that are member states of the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (Eumetsat), which operates Metop; and the European Space Agency (Esa), which leads weather satellite R&D in Europe.

British industry is keen to play its part and has put a case to government, through the UK Space Agency, to be allowed to develop the MHS follow-on instrument.

This will be known as MWS (MicroWave Sounder). It will do broadly the same as MHS but better (25 channels versus five channels).

It will also incorporate the observations of another current Metop instrument, Amsu (Advanced Microwave Sounding Units A1 and A2), which makes temperature profiles of the atmosphere.

"MHS is proven; it's a critical part of the forecast system. If we don't receive the data for some reason, the forecast degrades," says Brett Candy, a data assimilation scientist at the Met Office.

"For the future, we'd be looking for improved accuracy in the observations, hopefully improved resolution, perhaps more channels looking at different layers in the atmosphere - but really a continuation of the great instrument we've already got.".

And for Astrium, which now curates the Matra Marconi heritage, Mike Healy observed: "Sometimes, you put together a satellite instrument and there isn't a possibility of a follow-on.

"The nice thing here is that we have that possibility. The basis and all the lessons learned that were made for MHS - we can put that now into MWS, provided the UK subscription is big enough. This is about jobs and hi-tech manufacturing, so it should fit with the government's desire for growth," the director of the company's Portsmouth base said.

- Published17 September 2012

- Published14 September 2012

- Published6 July 2012

- Published15 March 2012

- Published16 November 2011

- Published28 October 2011

- Published25 February 2011