Curiosity Mars rover picks up the pace

- Published

The target rock has been named in honour of a rover engineer, Jake Matijevic, who died in August

The Curiosity rover is making good progress towards its first major science destination on Mars.

The vehicle has now driven 289m (950ft) since its landing on the Red Planet some six weeks ago.

It has perhaps another 200m still left to cover to get to a location dubbed Glenelg, where researchers expect to find an interesting juxtaposition of three types of geological terrain.

But before it goes any further, the rover, external will study a dark rock.

Measuring about 25cm in height and 40cm at the base, it is not expected to have major science value.

Rather, the rock provides an opportunity for the robot to use three of its survey instruments in tandem for the first time.

The rock has been named "Jake Matijevic, external" in honour of a Curiosity engineer who tragically died shortly after the vehicle touched down in Mars' Gale Crater on 6 August (GMT).

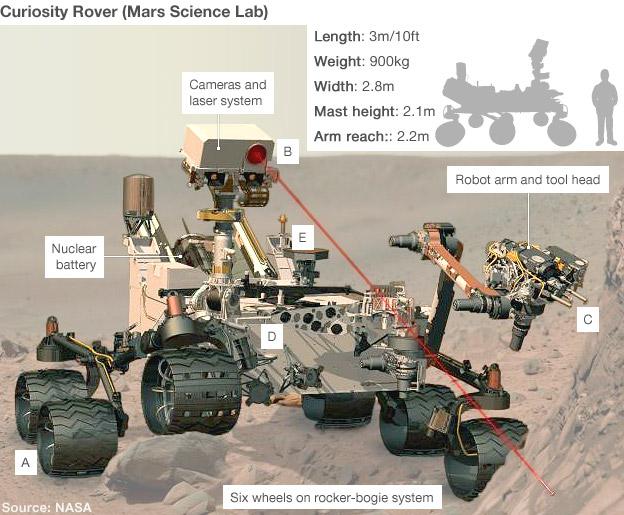

The rover will zap the rock from a distance with its ChemCam laser and examine it up close with its X-ray spectrometer, known as APXS. The latter device is held on the end of the rover's robotic arm; the laser is mounted on its mast.

The investigation will give a good idea of the atoms present in the Matijevic rock and its likely mineralogical composition - although the Curiosity science team fully expects to "discover" another ubiquitous lump of Martian basalt (a volcanic rock).

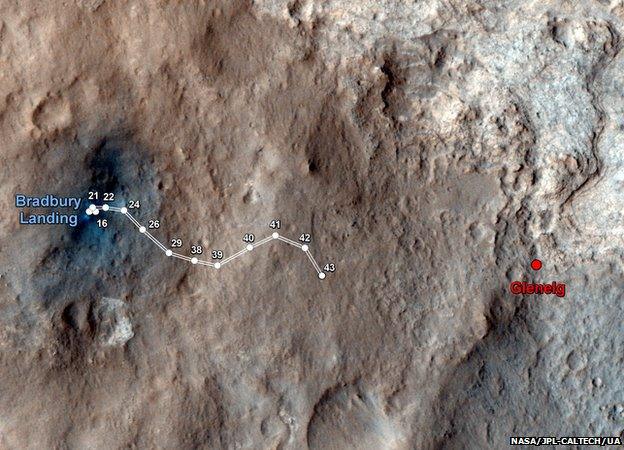

The rover's first major science destination, Glenelg, is still some 200m away (centre of image)

"It's a cool looking rock with almost pure pyramidal geometry," said Prof John Grotzinger, the mission's lead scientist. Such a shape was not uncommon, he explained, and probably reflected wind erosion processes.

"Our general consensus view is that these are pieces of impact ejecta from an impact somewhere else, maybe outside of Gale Crater, that throws a rock on to the plains, and it just goes on to sit here for a long period of time. It weathers more slowly than the stuff that's around it. So, that means it's probably a harder rock."

The point of the upcoming exercise is to demonstrate the procedure for selecting targets of higher importance - rocks that in future could have significantly more scientific interest and which might require a sample to be drilled and delivered to two sophisticated analysis labs inside the rover's body.

In a briefing with journalists on Wednesday, the US space agency (Nasa) also released pictures taken by the rover of the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos passing in front of the sun.

These transits are relatively rare - twice per Martian year, which is once every Earth year - but are of great interest to scientists trying to understand the internal make-up of the Red Planet.

"[The moons] have tidal forces that they exert on Mars; they change Mars' shape ever so slightly," explained Curiosity researcher Mark Lemmon from Texas A&M University, College Station.

"That in turn changes the moons' orbits - Phobos is slowing down, Deimos is speeding up (like our Moon is). This is something that is happening very slowly over time.

"And with the transits, we can measure their orbits very precisely and figure out how fast they're doing this. The reason that's interesting is because it constrains Mars' interior structure. We can't go inside Mars but we can use these transits to tell how much Mars deforms when the moons go by."

The rover has been taking pictures of the moon Phobos crossing the disc of the Sun

Curiosity has now spent 43 sols (Martian days) on the planet. Much of that time has been spent commissioning the rover's systems and instruments.

The vehicle was sent to Mars to try to understand whether past environments at its landing location in Gale Crater could ever have supported microbial life.

That question will more properly be addressed when it gets to the base of the big mountain (Mount Sharp) that dominates the centre of the 150km-wide equatorial depression.

Sediments at the lower reaches of the peak appear from satellite pictures to have been laid down in the presence of abundant water.

Curiosity will establish whether that is so, but it is unlikely to begin this particular investigation for many months.

The mountain target lies several km to the south-west of its current location, and the desire to see the interesting rocks at Glenelg is actually taking the vehicle in the opposite direction to Mount Sharp.

The science team is in no hurry, however. Curiosity is equipped with a nuclear battery and has ample power to complete its prime two-year mission. Further funding from Nasa could yet see this project drive and drive deep into the decade.

Since the rover started driving, it has covered almost 300m from its landing site, which was named in honour of the late science fiction writer Ray Bradbury

(A) Curiosity will trundle around its landing site looking for interesting rock features to study. Its top speed is about 4cm/s

(B) This mission has 17 cameras. They will identify particular targets, and a laser will zap those rocks to probe their chemistry

(C) If the signal is significant, Curiosity will swing over instruments on its arm for close-up investigation. These include a microscope

(D) Samples drilled from rock, or scooped from the soil, can be delivered to two hi-tech analysis labs inside the rover body

(E) The results are sent to Earth through antennas on the rover deck. Return commands tell the rover where it should drive next

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 September 2012

- Published12 September 2012

- Published10 September 2012

- Published30 August 2012

- Published28 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published20 August 2012

- Published20 August 2012

- Published17 August 2012

- Published9 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012