Dust-devils flirt with Curiosity Mars rover

- Published

Curiosity carries a weather station called Rems

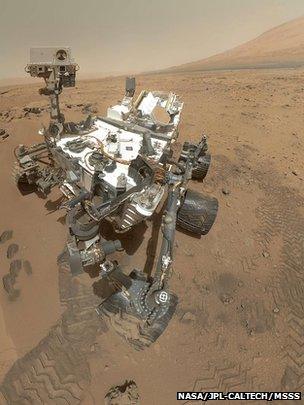

Nasa's Curiosity rover has been getting a good feel for the weather on Mars.

Although the robot's cameras have yet to catch sight of them, it seems whirlwinds of dust have been skirting around the six-wheeled vehicle.

From the data gathered by Curiosity's meteorological station, scientists think dust-devils may even have run over the mobile laboratory.

It is not entirely unexpected. Vortices of dust whipped up by the wind have been pictured by previous Mars rovers.

"A dust-devil looks essentially like what you would expect from the movies - a tiny tornado that is lifting dust," explained Manuel de la Torre Juarez of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and a scientist on the Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (Rems) instrument.

"Understanding these phenomena is very important because the Martian climate is driven largely by its dust cycle."

This is most evident when the planet is gripped by dust storms that can envelop the whole globe. Dust in the atmosphere warms it.

The Rems instrument was the sole part of the rover that suffered damage when it touched down in the equatorial Gale Crater back in August.

One of its two wind probes was knocked out, most probably by a piece of grit kicked up by the rocket-powered descent stage that placed Curiosity on the surface.

Nonetheless, Rems is returning very useful meteorological data, and scientists are learning to work around its deficiencies.

The instrument has established that winds generally blow east-west on the floor of the crater - something of a surprise to researchers who thought the rover's position close to the northern slopes of Gale's big central mountain might drive winds in a prevailing north-west direction as air moved up and down the peak in a day-night cycle.

Rems has also been tracking the hourly and daily changes in air pressure.

Barometric readings have a predictable behaviour to them that sees a sharp fall when the Sun comes over the crater every Martian sol (day) to heat the column of air, expanding it upwards and off to the sides. This has the effect of lowering air pressure at the surface.

But Curiosity has also experienced a general increase in air pressure over time. This is consistent with the southern hemisphere moving from spring to summer. The shift to higher temperatures prompts Mars' southern ice cap, which is made up entirely of frozen carbon dioxide, to start to evaporate and increase the mass of the atmosphere. In contrast, the northern hemisphere's ice cap will grow as CO2 comes out of the cooling air and builds up on the ground.

"Each year, the Martian atmosphere basically shrinks and grows by about 30% because a portion of the atmosphere is freezing out to the poles in [autumn] and then vaporising again in spring; and that of course is unlike anything we see on Earth," said Claire Newman, a Rems investigator at Ashima Research in California.

An interesting observation related to the rhythmical changes in air pressure has been made by another of Curiosity's environmental sensors - its Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD). This instrument was put on the rover to chart the likely radiation conditions future astronauts at Mars might experience.

RAD shows clearly that as air pressure increases at the end of the day, the total radiation dose recorded at the surface decreases. Simply put, when the atmosphere is thicker, it provides a better barrier with more effective shielding for radiation from outside of Mars.

One of Nasa's previous rovers, Spirit, caught a dust-devil on camera

"We certainly theorised that we would see variation with the seasons on Mars. I guess we were a little bit surprised at the sensitivity of the instrument that we could see [the daily variation]," said RAD principal investigator Don Hassler from the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado.

"The pressure varies by about 10% and we're seeing that crystal clear with the radiation measurements [having] a 3-5% variation. That's a little interesting."

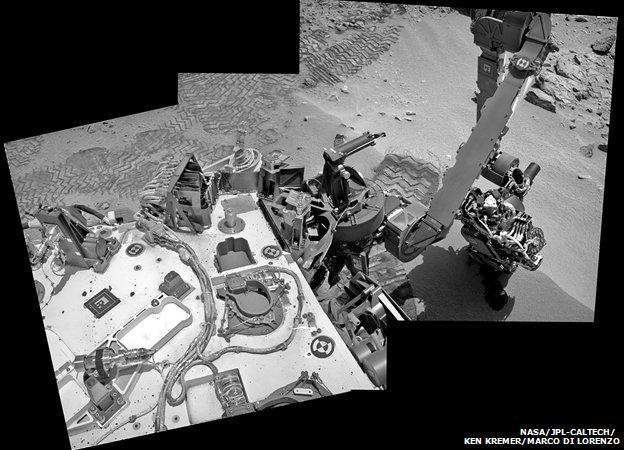

Curiosity has spent several weeks now parked at a sand dune dubbed "Rocknest", where it has been testing procedures for digging up soil samples and delivering them to the robot's big internal laboratories. Shortly, the vehicle will begin moving again, looking for a suitable rock on which to try out its drill.

Curiosity's mission has been funded for one Martian year (two Earth years) of study. It will try to determine in that time whether past environments at Gale Crater could ever have supported microbial life.

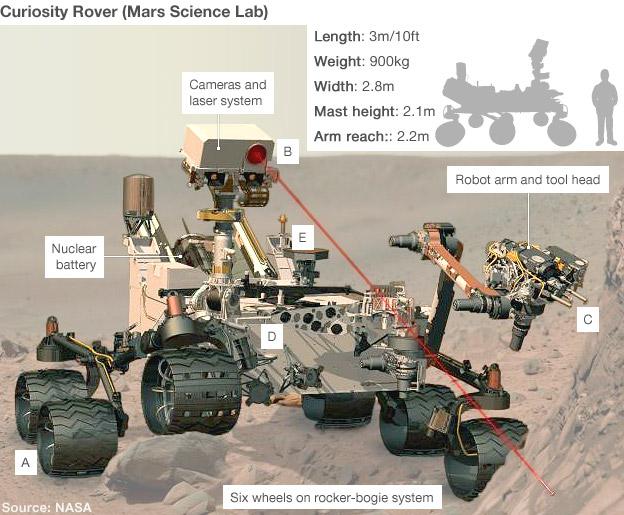

(A) Curiosity will trundle around its landing site looking for interesting rock features to study. Its top speed is about 4cm/s

(B) This mission has 17 cameras. They will identify particular targets, and a laser will zap those rocks to probe their chemistry

(C) If the signal is significant, Curiosity will swing over instruments on its arm for close-up investigation. These include a microscope

(D) Samples drilled from rock, or scooped from the soil, can be delivered to two hi-tech analysis labs inside the rover body

(E) The results are sent to Earth through antennas on the rover deck. Return commands tell the rover where it should drive next

Curiosity has spent several weeks now parked at a sand dune dubbed "Rocknest"

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published10 November 2012

- Published31 October 2012

- Published19 October 2012

- Published17 October 2012

- Published27 September 2012

- Published22 August 2012