Goce gravity mapper surfs atmosphere

- Published

Europe's ultra-low-flying gravity-mapping satellite, Goce, is being manoeuvred even closer to the planet.

The arrow-shaped spacecraft has spent most of its mission at an altitude of 255km - that's about 500km below most other Earth-observing missions.

Engineers are now bringing it down by 20km to improve its data resolution.

But it will be a tricky operation. Goce will have to fight atmospheric drag to stay aloft and maintain the stability needed to measure Earth's gravity.

"The science benefit that you get from decreasing the altitude and thereby increasing the spatial resolution of the data, and also the precision of what you can measure, is quite spectacular," explained mission manager Dr Rune Floberghagen.

"We will get about a 35% increase in the quality of the data," he told BBC News.

The Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer was launched in 2009.

It is part of a series of innovative research satellites developed by the European Space Agency (Esa).

It carries super-sensitive instrumentation to detect the tiny variations in the pull of gravity across the surface of the planet.

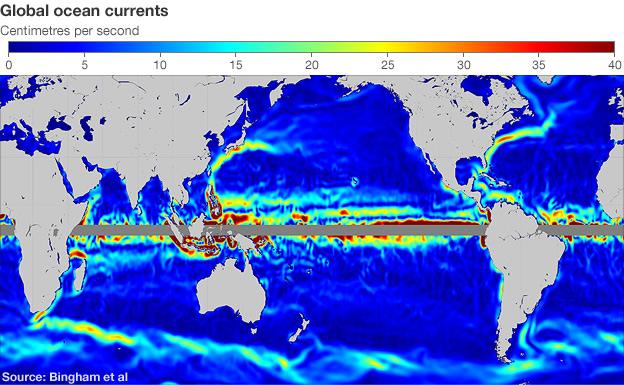

The maps it produces can have very broad applications. The data is a key reference in civil engineering for relating heights measured at widely separated locations, and for the computer models that need to understand how the oceans move to forecast future changes in climate.

To understand how the ocean currents move you need to know how gravity varies across the Earth

Recent successes include producing the first global high-resolution map of the boundary between the rocks of the Earth's crust and its mantle - the famous Mohorovicic (or "Moho") discontinuity, which lies tens of kilometres below the planet's surface.

But the gravity variations Goce seeks to document are so small it must get its gradiometer instrument as close as possible to the Earth.

The spacecraft's primary mission was conducted at an altitude of 255km - lower than any other major research satellite in service today.

Scientists have now requested that the last of vehicle's fuel be used to run a mapping campaign at an altitude of 235km.

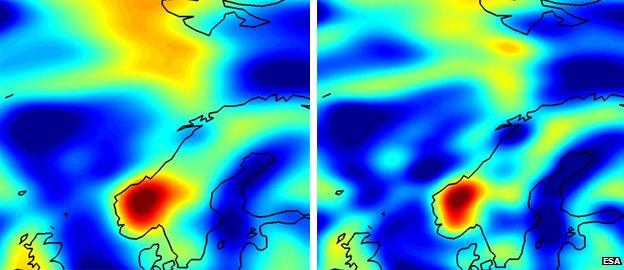

This will allow Goce to see even finer details such as the eddies that spin off large ocean currents.

"And we would be able to see not only the small features that have strong signals, but the large features that have weak signals. At the moment, there are some currents out there that are large and move a lot of water but they are less pronounced in the Goce data," said Esa's Dr Floberghagen.

Goce gravity signal (L) and the modelled expected improvement (R) from a 15km reduction in altitude

Controllers have been lowering the satellite by about 300m a day since August.

They hope to get it to the new target altitude by the end of January. This will necessitate Goce's ion engine having to work even harder.

This propulsion system produces exquisite levels of thrust by accelerating charged atoms of xenon through nozzles at the rear of the spacecraft.

The engine constantly throttles up and down, not only to counter the drag on the satellite from residual air molecules in near space but also to smooth the flight of the vehicle to minimise the noise in the gravity measurements.

Flying at 235km will allow little margin for error, especially if the Sun becomes more active. This has a tendency to heat and raise Earth's high atmosphere, buffeting Goce with stronger winds.

"If an anomaly were to happen in the ion propulsion system and we dropped out of our drag compensation mode, if we don't get control back in two days we may be so low in the atmosphere by the third day that we cannot get the satellite back. It will fall to Earth," Dr Floberghagen told BBC News.

As it is, Goce probably has sufficient xenon fuel only for another 50 weeks of operations. When the xenon does run down completely, the satellite will be pulled into the deep atmosphere within weeks to burn to destruction.

However, by then, the new high resolution gravity data should be safely on the ground.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 March 2012

- Published31 March 2011

- Published21 December 2010