Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer to release first results

- Published

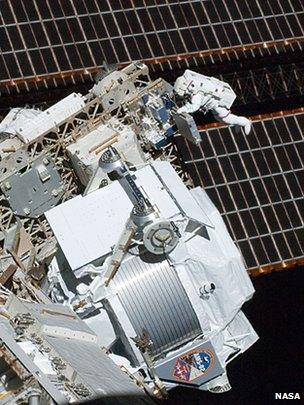

The AMS was taken up to the ISS in 2011

The scientist leading one of the most expensive experiments ever put into space says the project is ready to come forward with its first results.

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) was put on the International Space Station to survey the skies for high-energy particles, or cosmic rays.

Nobel Laureate Sam Ting said the scholarly paper to be published in a few weeks would concern dark matter.

This is the unseen material whose gravity holds galaxies together.

Researchers do not know what form this mysterious cosmic component takes, but one theory points to it being some very weakly interacting massive particle (or Wimp for short).

Although telescopes cannot detect the Wimp, there are high hopes that AMS can confirm its existence and describe some of its properties from indirect measures.

The imminent publication in an as yet undetermined journal will detail the progress of that investigation.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor said the project he first proposed back in the mid-1990s had now reached an important milestone.

"We've waited 18 years to write this paper, and we're now making the final check," he told reporters.

"I would imagine in two or three weeks, we should be able to make an announcement.

"We have six analysis groups to analyse the same results. Physicists as you know - everybody has their own interpretations, and we're now making sure everyone agrees with each other. And this is pretty much done now."

Sam Ting was speaking here in Boston at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), external.

His $2bn machine was taken up to the ISS in 2011 - on the final mission of Shuttle Endeavour.

The seven-tonne experiment holds a giant, specially designed magnet that bends the paths of particles that fall on it.

The way they bend reveals their charge, a fundamental property that, together with information about their mass, velocity and energy, garnered from a slew of detectors, tells scientists precisely what they are dealing with.

Prof Ting said that in its first 18 months of operation, AMS had witnessed 25 billion particle events.

Of these, nearly eight billion were fast-moving electrons and their anti-matter counterparts, positrons.

Colliding and annihilating Wimps ought to produce showers of these electrons and positrons. And it is by measuring the ratio of the latter to the former, and the behaviour of any excess across the energy spectrum, which may provide a way into the dark matter problem.

"The smoking gun signature in the positron to electron ratio is a rise and then a dramatic fall. That is the key signature for the dark matter annihilation in our galaxy's halo," observed Prof Michael Turner from the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics, University of Chicago. Prof Turner is not part of the AMS Collaboration.

"Also in this energy regime, is there anisotropy? Do the positrons come from a fixed direction or all directions?" Prof Ting pondered to the BBC.

"Dark matter is supposed to be everywhere. So if we see the positrons coming from a particular direction, it means astrophysics like a pulsar (a type of neutron star) is responsible for the signal, not dark matter."

The AMS paper will report the positron-electron ratio in the mass range of 0.5 to 350 Gigaelectronvolts. This covers territory at the top end where some other experiments have already reported tantalising hints of dark matter.

Prof Turner said science was closing in on its quarry.

He predicted the next few years would be remembered as the "decade of the Wimp", and looked forward to dark matter's properties being exposed via a number of investigation strands that included Wimp production at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

"Theory says that this particle might weigh somewhere between 30, 40 and 300 times what the proton does, so somewhere between 30 and maybe 1,000 GeV.

"The LHC can produce particles of that mass, Sam Ting's AMS detector can see particles of that mass annihilating, and then the detectors deep underground are also sensitive to particles of this mass.

"If we get very lucky, if Santa answers our wish-list, we could get a triple signature of the dark matter particle, by seeing the annihilations, by directly detecting it, by producing it at the LHC - all three of these methods are sensitive across the same mass range."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 January 2013

- Published19 May 2011

- Published27 April 2011

- Published17 May 2011