Science 'javelins' spear Pine Island Glacier

- Published

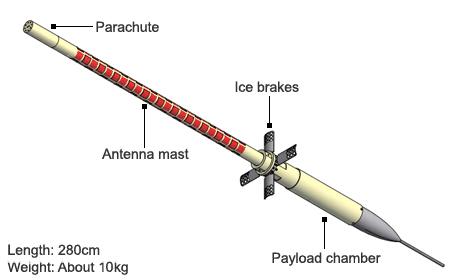

The javelin's tail sticks vertically out of the snow/ice surface, ensuring good communications

UK scientists have developed an air-dropped projectile to put instruments in some of the most inaccessible places in Antarctica.

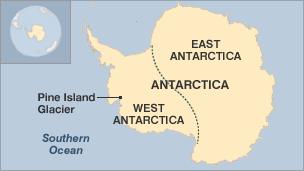

Twenty-five of the "javelins" are currently sticking in Pine Island Glacier (PIG), one of the continent's biggest and fastest-moving ice streams.

The PIG has many deep crevasses that are too dangerous to traverse.

The British Antarctic Survey's, external spears have been equipped with GPS to track the PIG's progression towards the sea.

"Our javelins mean we can now instrument areas that were previously out of reach," said Dr Hilmar Gudmundsson.

"And in Pine Island Glacier, we are monitoring the region of Antarctica where the greatest changes are taking place," the BAS glaciologist told BBC News.

The slender javelins are very similar to "sonobuoys" - the floating instruments that are dropped from aeroplanes to study the oceans.

Like sonobuoys, the new BAS projectiles are released down a tube and exit from the belly of an aircraft.

They fall rapidly towards the ice, using a 20cm-wide parachute to stabilise their descent.

When javelins hit the surface, they are travelling at about 50m per second (120mph) and have had to be engineered to withstand the high g-forces associated with a very rapid deceleration.

Small fins, or ice brakes, fitted to the sides of the spears prevent them from driving too deep.

This ensures the tail of the javelin containing its satellite communications antenna sticks upright above the snow and is able to relay the GPS data back to BAS.

Dr David Jones describes the javelin design to Jonathan Amos

"The javelins need to go to a certain depth so that they don't get blown over by the wind. On the other hand, the mast must be sufficiently tall that it doesn't get buried by snow," explained Dr David Jones, who leads the technical development on Project Javelin.

"Machining these fins so that they could stop the devices going in any deeper than one metre but at the same time not introduce any aerodynamic instabilities in flight - that was a huge task."

Part of the solution was incorporating a series of holes in the fins.

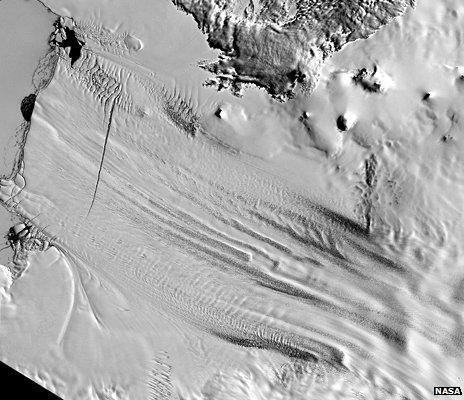

Wind tunnel tests led to the most stable javelin configuration

The team spent a lot of time perfecting the design, even conducting experiments in a vertical wind tunnel.

Dr Hilmar Gudmundsson: "PIG is the region in Antarctica where we see the largest changes in velocity"

"These are generally used for indoor skydiving," Dr Jones said.

"The one we used was originally built to test parts for Concorde and then became a recreational centre; and we asked if we could have it back for a little bit more science."

Initial drop trials of the battery-powered javelins at Scar Inlet on the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula proved successful in January.

This led the team then to release 33 of the devices over the PIG. A high proportion, 25, survived the violent emplacement and return daily data. BAS expects a two-year lifetime for the devices.

The PIG and its floating ice shelf are the subjects of intense study

The PIG is one of the most intensively studied areas of Antarctica because it drains something like 10% of all the ice flowing off the west of the continent, making a significant contribution to global sea level rise.

In recent years, satellite and airborne measurements have recorded a marked thinning and a surge in velocity.

A zone of particular interest to scientists is just upstream of the grounding line, where the ice flowing off the land starts to float out over the ocean.

But this zone is precisely where the crevasses are most extensive, making it extremely difficult for researchers to get in and set up instruments.

"That's where you want to be, so to have sensors there now is just fantastic," Dr Gudmundsson told BBC News.

"The javelins will provide us with a dataset with which we can validate our numerical models. And it's with the numerical models that we will be able, hopefully, to address the question: what will happen at Pine Island Glacier in 10 years' time, in 20 years' time, in 30 years' time, in a 100 years' time?"

Project Javelin was presented here in Vienna at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly. The development was funded by the UK's Natural Environment Research Council, external (NERC).

Some of the places scientists would like to put instruments are extremely hazardous

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published8 March 2013

- Published25 April 2012

- Published19 August 2011