Journeys of discovery from Cortez to Cayman

- Published

- comments

The Western Flyer took Steinbeck (R) and Ricketts on their journey

An overloaded sardine boat set sail from Monterey in California in 1940 on a journey remarkable not for its ambition but for the place it would earn in the literature of marine discovery.

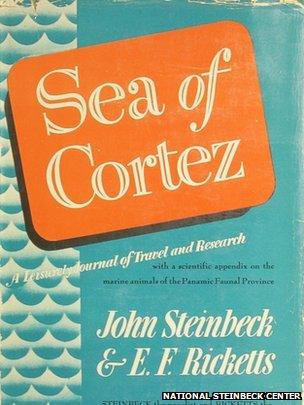

The book describing the expedition, "The Log from the Sea of Cortez", was a masterpiece - charming, perceptive and honest about the reality of scientific fieldwork.

And it remains highly relevant today.

Many of its observations - by the writer John Steinbeck and his friend Ed Ricketts, a biologist - were to ring true on my visit to a British research vessel, the James Cook, in the Caribbean earlier this year.

Steinbeck would later become one of America's most famous authors for Grapes of Wrath, his searing account of families fleeing the Oklahoma dust bowl for a new life in California.

But back in 1940 he had the time to join Ricketts on an expedition with a very modest aim: investigating the worms, crabs and clams inhabiting the tidal zone of the Mexican shore.

'Horizonless'

Their account not only conveys the hardships, triumphs and humour of attempting research at sea but it also highlights the power of science to support a basic human motivation: curiosity.

"We wanted to see everything our eyes could accommodate," Steinbeck and Ricketts wrote, "with a view as wide and horizonless as that of Darwin…"

The book is still read by budding oceanographers

So they ventured into the Gulf of California in the same spirit as the scientists on board the James Cook who were exploring the almost alien hydrothermal vents in an underwater canyon known as the Cayman Trough.

On the face of it, the two voyages had very little in common. One involved an ultra-modern science vessel brimming with high technology while the other was "makeshift", as Steinbeck and Ricketts themselves admitted.

As a hired fishing boat, the Western Flyer that carried them had no laboratory. The microscopes, along with some of the chemicals, had to be stored on the bunks.

A wooden case holding important reference books and charts - essential for the research effort - turned out to be too large to be stored anywhere except the roof of the deckhouse where it was lashed under tarpaulins which made it virtually inaccessible.

"We had no dark-room, no permanent aquaria, no tanks for keeping animals alive, no pumps for delivering fresh sea water. We had not even a desk except the galley table."

The one small fridge, intended to cool seawater to help keep samples alive, ended up being used less for science and more to chill the beer.

As a result, Steinbeck and Ricketts concluded that "all collecting trips to fairly unknown regions should be made twice; once to make mistakes and once to correct them".

'Peephole'

By contrast the James Cook, run by the UK's National Oceanography Centre, was built for research. It is a floating campus with professors and students busy with instruments and computers in suites of labs.

And the ship also provides something unimaginable to earlier generations of marine scientist: a remotely-operated submarine that glides above the seabed and relays back live video, even from three miles deep. The sights can be spellbinding.

But I soon found that the expeditions, though poles apart in terms of capability, shared something fundamental: a passion for discovery and understanding.

Steinbeck had once written about the value of exploration. "Every new eye applied to the peephole which looks out at the world may fish in some new beauty and some new pattern…"

The James Cook is equipped with a state-of-the-art laboratory

For him and Ricketts, the peephole involved the hard graft of waiting for low tide so they could clamber through the mud to observe and collect along the shore. Braving stings and cuts, they relished moments of revelation about new creatures and the workings of "teeming, boisterous life".

They were thrilled to realise the potency of what they were studying: "life in every form is incipiently everywhere waiting for a chance to take root…"

So they would have instantly recognised the buzz that electrified the James Cook at a key moment. The ISIS, the robot submarine, reaching the seabed, provided the ultimate 'peep-hole' with high-definition video showing twisted, belching hydrothermal vents that no human eye had ever seen before.

The tiny control room where the "pilots" controlled the sub was suddenly packed. Crewmen, engineers and scientists all strained for a view of an unearthly realm. We were all amazed by swarms of albino shrimp jostling on the rocks. Who wouldn't be? Discovery is irresistible.

The tiny shrimp fight for the best positions from which to feed on bacteria in an exceptionally narrow zone where the temperature and chemistry are just right: between the scalding vent water and the icier water of the surrounding sea.

The animals Steinbeck and Ricketts collected also depended on a very specific set of conditions in a similarly narrow zone, in their case found in the mud and rock between the reach of the high and low tides.

They - and the scientists on the James Cook - were trying to understand how life works in such tightly defined areas and how some forms of life can thrive where others wouldn't cope.

Returning to Monterey with a hold-full of samples, Steinbeck and Ricketts came up with a memorable conclusion about the resilience of living things: "Let a raindrop fall," they wrote, "and it is crowded with the waiting life."

'Open-minded'

Views of deep sea vents are captured by the James Cook's submarine

The James Cook too returned laden with samples - shrimp and tube-worms, rocks and gases - crossing the Atlantic to reach the National Oceanography Centre at Southampton in March.

As always after fieldwork, months of analysis were to lie ahead, and expedition leader Dr Jon Copley and his colleagues hope their turn at the "peep-hole" will have allowed them to detect not just "new beauty" but also a "new pattern".

Not surprisingly, Dr Copley is such a fan of Sea of Cortez that he recommends it to his first year undergraduates.

"So much is so recognisable to our kind of fieldwork," he said. "The book is a real insight into what it's like to do science at sea.

"It's about making a journey into the unknown, trying to work out what's going on while hopefully remaining open-minded - and I adore it."

The Sea of Cortez tells Jon Copley - and his fellow scientists and students - that the science is never complete and that "an answer is invariably the parent of a great family of new questions".

David Shukman presents "Treasures of the Deep" on Our World on the BBC News Channel on 29 June and on BBC World on 28-30 June .