Esa's Cryosat mission observes continuing Arctic winter ice decline

- Published

Cryosat was launched with the specific aim of measuring Arctic sea-ice thickness

The volume of sea ice in the Arctic hit a new low this past winter, according to observations from the European Space Agency's (Esa) Cryosat mission.

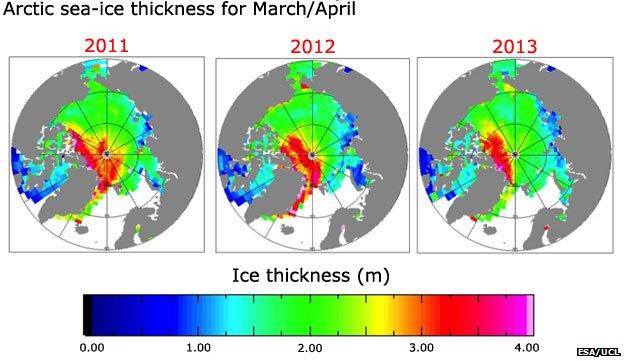

During March/April - the time of year when marine floes are at their thickest - the radar spacecraft recorded just under 15,000 cu km of ice.

In its three years of full operations, Cryosat, external has witnessed a continuing shrinkage of winter ice volume.

It underlines, say scientists, the long-term decline of the floes.

The animation shows the ebb and flow of sea-ice thickness and area during Cryosat's time in orbit (Planetary Visions)

Thirty years ago, there were perhaps 30,000 cu km at the height of winter.

While there has been a great deal of attention focused of late on the falling extent (area) of sea ice in the Arctic, especially during summer months, researchers emphasise that it is volume that provides the most reliable assessment of the changes now underway in the northern polar region.

The provisional Cryosat data was presented here at Esa's Living Planet Symposium, external in Edinburgh, UK.

Prof Andy Shepherd, from Leeds University, said: "Now that we have three years of data, we can see that some parts of the ice pack have thinned more rapidly than others. At the end of winter, the ice was thinner than usual. Although this summer's extent will not get near its all-time satellite-era minimum set last year, the very thin winter floes going into the melt season could mean that the summer volume still gets very close to its record low," he told BBC News.

And Rachel Tilling, who is working through the data at University College London (UCL), added: "Cryosat will be able to confirm whether or not a minimum volume was reached this summer once the ice starts to refreeze in the Autumn."

Cryosat was launched by the European Space Agency in 2010.

It is what is known as an altimetry mission, using advanced radar to measure the difference in height between the top of the marine ice and the top of the water in the cracks, or leads, that separate the floes.

From this number, scientists can, with a relatively simple calculation, work out the thickness of the ice. Multiplying by the area covered by ice gives a volume.

"In terms of really understanding what is going on in the Arctic and trying to put the changes we see in the larger scale context - volume is the key part of the story," explained Prof Alan O'Neill, chairman of Esa's Earth Science Advisory Committee.

"If you just looked at ice area, for example, this could reflect simply the piling up of ice as a result of ocean currents and winds.

"What Cryosat has done in the past three years is to confirm the volume decline predicted by the modelling from the atmospheric record.

"The $64,000 question is what's causing this decline? It's certainly consistent with what we expect from global warming, but we also need to understand better the natural variation that occurs in the system on perhaps decadal timescales. Cryosat can begin to help us do that as well."

The European Space Agency expects Cryosat to keep flying for years to come; it has sufficient resources onboard to work until perhaps 2020.

"The satellite health is very good," said mission manager Dr Tommaso Parrinello.

"We have now funds to operate the mission for another three years, pending a science verification next year, and we are confident that CryoSat will contribute even more to understanding how Earth's ice fields are reacting to global warming," he told BBC News.

The Living Planet Symposium paid tribute this week to the two British scientists who had led the interpretation of Cryosat data since its launch.

Dr Seymour Laxon and Dr Katharine Giles, both of UCL, died in separate accidents earlier this year, and the conference dedicated a special session to their contributions to the science of sea ice measurement from space.

The opening address was delivered by Prof Duncan Wingham, who was Cryosat's principal investigator at its launch and who is now the chief executive of the UK's Natural Environment Research Council.

"In those months earlier this year, we lost straightforwardly 45 years of experience in a technique and a subject that is not well understood or well known in our community," he told the meeting. "But in UCL, we lost more than that. Seymour and Katharine were very central to our way of working and central to the successes we had over the last decade."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 July 2013

- Published13 February 2013

- Published29 November 2012

- Published24 April 2012

- Published19 August 2011

- Published5 December 2011