Kiribati island: Sinking into the sea?

- Published

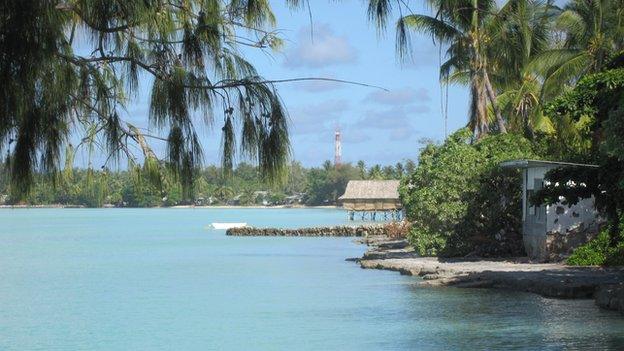

The stereotypical image of Kiribati is of classic pacific atolls, palm trees and coral reefs

Lying just two metres above sea level at its highest points, the island nation of Kiribati is the poster child for climate change, with predictions that many of the 32 islands in the group could be lost to the sea in the next 50 years.

But what is it really like? Julian Siddle from BBC Science reports from South Tarawa, Kiribati's main island.

The stereotypical image of Kiribati is of classic pacific atolls, palm trees, coral reefs and people living a simple lifestyle, able to fish in abundant seas. But it is threatened by rising sea levels and facing the full force of climate change.

All that is real, but in addition this island nation is one of the most populated places on earth. Current estimates suggest around 110,000 people live here, and half of these in South Tarawa - a chain of small islands, sharing a lagoon and coral reefs now linked by concrete causeways topped with a dusty road.

The population has boomed since the island obtained independence from Britain in the late 1970s. Villages are now joined, forming a near continuous strip of urbanisation along the roadside and down to the sea.

A shortage of land means there is very little agriculture and the population is now heavily reliant on imported and predominantly processed food.

Many people come from the rural outer islands to the urban centre of South Tarawa. This has been a largely economic migration, though a loss of land to the sea has also provided a push.

"The outer island communities have been affected, we have a village which has gone, we have a number of communities where the sea water has broken through into the freshwater pond and is now affecting the food crops," says Kiribati's president, Anote Tong.

"That is happening on different islands, it's not an isolated event, serious inundation is being witnessed. These are the realities we are facing, whether they are climate change induced or not."

The less populated Island of Abaiang to the north of Tarawa is where a village disappeared beneath the waves. This island has a much lower population than Tarawa, approximately 10,000.

The future of Abaiang’s coconut plantations is uncertain

This means there is enough land on which to grow food, staples include breadfruit and coconut. However there are concerns over the long term sustainability of these crops.

"We see our coconut trees are less productive. The weather is changing. The trees we rely on, they are drier," says Anata Maroieta, vice mayor of Abaiang island council.

With reluctance the island has begun to accept plans from the aid agencies to develop Abaiang as a potential food exporter - with South Tarawa providing the main market. Abaiang is now accepting that producing a food surplus might be the key to its future survival.

"Worries over our own food means we accept these new ideas on food crops," says the vice mayor.

Despite its lack of food security, South Tarawa provides an illusion of security in another way. Much of the island is heavily fortified with sea walls, partly built by the local population from rock mined from the surrounding reef.

More recent walls protecting the road system are made from concrete filled sandbags. Unfortunately both types of sea defence are having a detrimental effect.

"The hard sea walls reflect back the force of the waves, just moving erosion to unprotected areas," says coastal engineer Cliff Jullerat, who works with Kiribati's ministry of public works and utilities.

"They're a civil engineering solution, rather than marine."

Concrete sea walls designed to protect the coastline can make erosion worse

Even though his post is funded by the World Bank, he is critical of steps taken in earlier stages of the World Bank-funded Kiribati Adaptation Project, which built much of the now failing concrete structures.

The most dramatic example of this is a huge sea wall built to protect a water pipe, electricity and phone cables running next to a causeway road. The design of the wall created erosion, an even greater area of pipes and cabling was exposed - right next to the wall - threatening the fresh water supply for most of the island's population.

Mr Cliff says alternative measures should have been considered.

"As a coastal engineer I would never recommend sea walls. There are a range of offshore devices that can dissipate the waves and soft solutions such as planting mangroves which encourage the formation of new land."

The causeways themselves can be considered the greatest environmental disaster, as they block the flow of water between the island's lagoon and the ocean.

Without the ocean's washing effect the lagoon has become heavily polluted. There are serious problems with domestic rubbish human and animal excrement entering the waters. Bacterial infections and diarrhoea have the potential to be life threatening.

South Tarawa’s beaches are strewn with rubbish

President Tong says that, given these immediate problems of overpopulation and environmental degradation, it's hard for people trying to survive here to get a perspective on the wider threat of climate change:

"They don't have the resources to deal with things that will not directly affect them in their lifetimes. We are very vulnerable. We are on the front line."