Esa's Cryosat mission detects continued West Antarctic ice loss

- Published

West Antarctica continues to lose ice to the ocean and this loss appears to be accelerating, according to new data from Europe's Cryosat spacecraft.

The dedicated polar mission finds the region now to be dumping over 150 cubic km of ice into the sea every year.

It equates to a 15% increase in West Antarctica's contribution to global sea level rise.

Cryosat was launched in 2010 with a radar specifically designed to measure the shape of ice surfaces.

And the instrument's novel design, scientists believe, is enabling the European Space Agency satellite to observe features beyond the capability of previous missions.

The new study, presented here in San Francisco to the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, external, confirms the usual suspects to be involved in the increased ice loss.

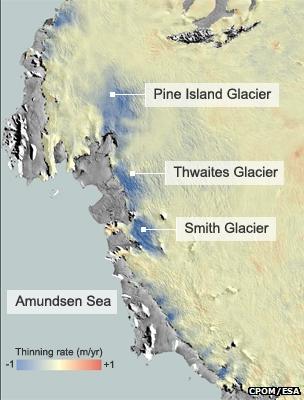

They are Pine Island, Thwaites and Smith Glaciers.

These major glaciers and their associated tributaries drain the interior of West Antarctica, taking its mass into the Amundsen Sea.

The ice near to their grounding lines - the places where the ice streams lift up off the land and begin to float out over the ocean - is now thinning by between four and eight metres per year.

"Interestingly, Smith Glacier is thinning fastest," said study leader Dr Malcolm McMillan from the UK's Nerc Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM).

"It's smaller but its thinning rate is roughly double that of Pine Island or Thwaites, which tend to get all the headlines because they have such huge catchments," he told BBC News.

In a recent major review of all satellite data, scientists concluded that ice losses from West Antarctica pushed up global sea levels by some 0.28mm a year between 2005 and 2010.

The new Cryosat data picks up from the end of that period, and suggests the contribution has risen still further.

Cryosat's double antenna configuration allows it to map slopes very effectively

However, the mission's researchers caution that some of the increase may simply be the result of Cryosat's exceptional radar vision.

With two antennas slightly offset from each other, the spacecraft's instrument is tuned to sense not just the height of the ice but the shape of its slopes and ridges.

This interferometric observing mode, as it is known, makes Cryosat much more sensitive to details at the edges of the ice sheet - the locations where thinning is most pronounced.

"Cryosat's new mode was designed with the express purpose of detecting changes in coastal regions of the polar ice sheets and, although this first glimpse confirms the design is a roaring success, sadly, it reveals also that there has been no let-up in the rate of ice loss from West Antarctica," added Prof Andy Shepherd of Leeds University, a co-author on the study.

"Nevertheless, it's important to take care when interpreting these measurements.

"Although some of the changes are due to increased ice thinning, others are related to Cryosat's capacity to observe previously unseen terrain and, of course, three years is a very short period for detecting trends.

"The longer we are able to fly this exceptional mission, the more certain we will be about making comparisons to the past."

Parts of West Antarctica are undergoing significant change

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published9 September 2013

- Published2 July 2013

- Published29 November 2012

- Published24 April 2012

- Published5 December 2011