Jupiter's icy moon Europa 'spouts water'

- Published

Water spouts taller than Mt Everest appear to burst out of Europa when it is farthest from Jupiter

Water may be spouting from Jupiter's icy moon Europa - considered one of the best places to find alien life in the Solar System.

Images by the Hubble Space Telescope show surpluses of hydrogen and oxygen in the moon's southern hemisphere, say astronomers writing in Science journal, external.

If confirmed as water vapour plumes, it raises hopes that Europa's underground ocean can be accessed from its surface.

Future missions could probe these seas for signs of life.

Nasa's planetary science chief Dr James Green told BBC News: "The presence of the water has led scientists to speculate that the Europa we know today harbours life.

"The plumes are incredibly exciting if they are there - they are bringing up material from the ocean. Perhaps there are organic molecules lying there on the surface of Europa."

The findings were reported at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, external in San Francisco, California.

Scientists discovered the enormous fountains in images taken by Hubble in November and December of last year, as well as older images from 1999.

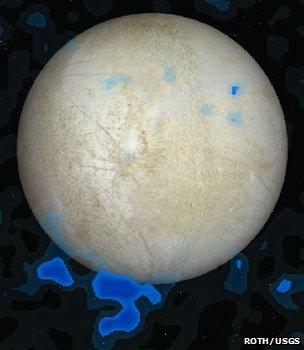

Signatures of water (blue) detected by Hubble are overlayed on an image of Europa

They saw evidence of water being broken apart into hydrogen and oxygen over the south polar regions of Europa.

"They are consistent with two 200-km-high (125 mile-high) plumes of water vapour," said lead author Lorenz Roth, of Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

Every second, seven tonnes of material is ejected from the moon's surface.

Dr Kurt Retherford, also of the Southwest Research Institute, told the AGU meeting: "This is just an amazing amount.

"It is travelling at 700m a second... All of this gas comes out, and almost all falls back towards the surface - it doesn't escape out into space."

These plumes appear to be transient - they arise for just seven hours at a time.

They peak when Europa is at its farthest from Jupiter (the apocentre of its orbit) and vanish when it comes closest (the pericentre).

This means that tidal acceleration could be driving water spouting - by opening cracks in the surface ice, the researchers propose.

The team is not yet sure whether these fissures go all the way down to the liquid water beneath the moon's icy crust, or whether some other mechanism is bringing the vapour to the surface.

The researchers also want to investigate whether the plumes are similar to those seen on Saturn's moon Enceladus, where high-pressure vapour emissions escape from very narrow cracks on the body's surface.

"We have a lot of questions about how this works," said Dr Retherford.

"How thick is the ice crust? Are there lakes and ponds embedded within the layers of the ice? Do these cracks go down really deep, do they really touch the liquid water down below?

"We don't know all of these things."

The team said exploration for Europa should now be made a priority.

The US Space Agency has made some preliminary plans for a mission to the moon - the Europa Clipper, which could fly past the plumes.

However, budgetary constraints mean it may not happen for some time.

Dr Green said: "The Europa Clipper is a very expensive venture. It is expensive because it is designed to last for a fairly long period of time, potentially a year or a number of years in a very harsh radioactive environment.

"So consequently that is what we would call a flagship.

"And right now, the budget horizon is such that we are deferring that kind of mission later into the decade."

The next realistic opportunity to study the jets up close is therefore the European Space Agency's Juice mission.

Due to launch to the Jovian system in 2022, the satellite will make two close flybys of the ice-encrusted moon in the 2030s. With luck, its instrumentation will get close enough to directly sample the plumes.

Dr Retherford, who is also an investigator on a US instrument on Juice, cautioned that the European flybys would go close to the equator, whereas the Hubble data had only seen the plume activity at the southern pole so far: "We have probably observed only one of the largest plumes on Europa.

"There could be a lot of plumes, more like 10-50km high, and we're just not seeing them with our current data-sets. So it's not improbable that the Juice mission could be flying through some sort of plume near the equator, in which case we'd still have a chance to sniff out the composition of the gases coming off and do all sorts of other interesting studies," he told BBC News.

Study author Britney Schmidt says life may exist on Europa

- Published16 November 2011

- Published2 May 2012

- Published11 December 2013