Gaia 'billion-star surveyor' lifts off

- Published

Launch of the Gaia satellite from the Sinnamary complex in French Guiana

Europe has launched the Gaia satellite - one of the most ambitious space missions in history.

The 740m-euro (£620m) observatory lifted off from the Sinnamary complex in French Guiana at 06:12 local time (09:12 GMT).

Gaia is going to map the precise positions and distances to more than a billion stars.

This should give us the first realistic picture of how our Milky Way galaxy is constructed.

Gaia's remarkable sensitivity will lead also to the detection of many thousands of previously unseen objects, including new planets and asteroids.

Separation from the Soyuz upper-stage was confirmed just before 10:00 GMT.

The satellite is now travelling out to an observing station some 1.5 million km from the Earth on its nightside - a journey that will take about a month to complete.

Gaia has been in development for more than 20 years.

It will be engaged in what is termed astrometry - the science of mapping the locations and movements of celestial objects.

To do this, it carries two telescopes that throw light on to a huge, one-billion-pixel camera detector connected to a trio of instruments.

Gaia will use this ultra-stable and supersensitive optical equipment to pinpoint its sample of stars with extraordinary confidence.

Gaia - The discovery machine

Gaia will make a very precise 3D map of our Milky Way Galaxy

It is the successor to the Hipparcos satellite which mapped some 100,000 stars

The one billion to be catalogued by Gaia is still only 1% of the Milky Way's total

But the survey's quality promises a raft of discoveries beyond just the star map

It will find new asteroids and planets; It will test physical constants and theories

Gaia's sky map will be the reference to guide future telescopes' observations

By repeatedly viewing its targets over five years, it should get to know the brightest stars' coordinates down to an error of just seven micro-arcseconds.

"This angle is equivalent to the size of a euro coin on the Moon as seen from Earth," explained Prof Alvaro Gimenez, Esa's director of science.

Gaia will compile profiles on the stars it sees.

As well as working out how far away they are, the satellite will study their motion across the sky.

Their physical properties will also be catalogued - details such as brightness, temperature, and composition. It should even be possible then to determine their ages.

And for about 150 million of these stars, Gaia will measure their velocity either towards or away from us.

This will enable scientists to use them as three-dimensional markers to trace the evolution of the Milky Way, to in essence make a time-lapse movie that can be run forwards to see what happens in the future, or run backwards to reveal how the galaxy was assembled in the past.

And because Gaia will track anything that passes across its camera detector, it is likely also to see a colossal number of objects that have hitherto gone unrecorded - such as comets, asteroids, planets beyond our Solar System, cold dead stars, and even tepid stars that never quite fired into life.

"It will allow us, for the first time ever, to walk through the Milky Way - to say where everything is, to say what everything is. It is truly a transformative mission," said Prof Gerry Gilmore from Cambridge University, UK, external.

By the end of the decade, the Gaia archive of processed data is expected to exceed 1 Petabyte (1 million Gigabytes), equivalent to about 200,000 DVDs of information.

This store is so vast that it will keep professional astronomers busy for decades.

"To think that you see individual scientific papers coming out now that talk about just a single object - a single star or exoplanet. And very soon, because of Gaia, we will have information on a billion objects. What will the scientific literature look like then?" pondered Dr Michael Perryman, the former Gaia Esa project scientist now affiliated to Princeton University, US.

"Of course, there will be big statistical projects you can tackle with this data, but it is clear the scale of Gaia means this information is not going to be superseded for a very long time," he told BBC News.

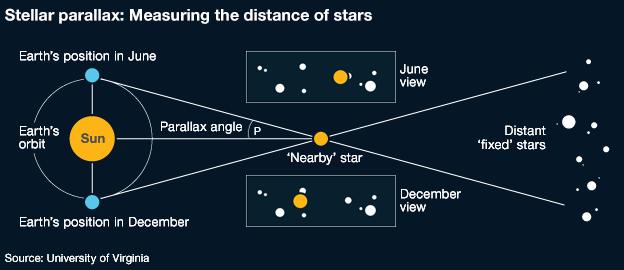

As the Earth goes around the Sun, relatively nearby stars appear to move against the 'fixed' stars that are even further away

Because we know the Sun-Earth distance, we can use the parallax angle to work out the distance to the target star

But such angles are very small - less than one arcsecond for the nearest stars, or 0.05% of the full Moon's diameter

Gaia will make repeat observations to reduce measurement errors down to seven micro-arcseconds for the very brightest stars

Parallaxes are used to anchor other, more indirect techniques on the 'ladder' deployed to measure the most far-flung distances

It will though offer ample scope for citizen scientists to mine Gaia's data to make their own discoveries, and a number of crowdsourcing projects to facilitate this activity will get under way next year.

Gaia is the result of an enormous industrial effort led by Astrium satellites in Toulouse, France. "For this masterpiece, for this jewel of space hardware, Astrium gathered and led an industrial consortium made up of 50 companies - 47 European, three North American," said CEO Eric Beranger.

"Coming to [French Guiana] and seeing our satellite lifting off brings me huge emotion. So much effort, dedication and ingenuity captured in just a few minutes."

Jon Kemp from e2v - the UK company that produced Gaia's camera detector - explains how it works

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published28 November 2013

- Published21 August 2013

- Published10 October 2011

- Published20 July 2010