Will crushing ivory curb poaching?

- Published

- comments

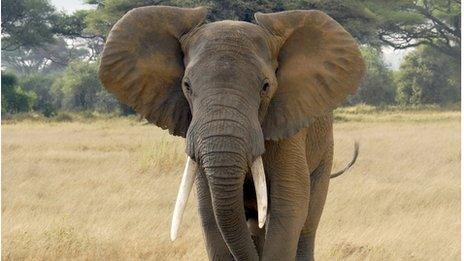

China's destruction of seized ivory is seen as a significant step against the illegal trade

China has become the latest country to carry out a public destruction of seized ivory, crushing some six tonnes of tusks and other pieces at a ceremony in Guangdong.

Last November, the United States crushed around five tonnes in a similar exercise.

Ivory has also been publicly destroyed at events in Kenya, Gabon and the Philippines.

These public displays of disaffection with ivory have been designed to curb the illegal trade in tusks that saw around 22,000 elephants slaughtered in 2012, external according to CITES - the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species.

Demand driven

Because China is the world's biggest destination for illegal ivory, the latest move is even more significant according to CITES secretary-general John Scanlon.

"China is sending an unequivocal message - both domestically and internationally - that it will not tolerate this illegal trade," he said.

"We hope that the underlying messages being conveyed through today's public crush of seized ivory are heard loud and clear by anyone who is involved in this highly destructive illicit activity."

Campaigners have also welcomed the move, saying that destroying ivory would help to cut demand for tusks.

But this is a very complex business.

Although there has been a ban on the international trade in ivory since 1990, legal sales of ivory products continue to take place in the US and in China.

To make matters more tricky, there have been two legally sanctioned international sales of ivory stocks in 1999 and 2008. The first involved Japanese traders buying ivory direct from Africa. The second saw sales to China as well.

Some critics are concerned that destroying stocks of ivory gives an incentive to poachers

According to Tom Milliken from Traffic, the wildlife trade monitoring organisation, the way that China has handled these purchases has exacerbated the problem of poaching.

"The legal source of ivory remains in the hands of the Chinese Arts and Crafts Association. Although they purchased it for less than $150 a kg, they have been selling it at highly inflated prices in China.

"I think what we are seeing is that the black market price undercuts that legally controlled system and that has produced a very perverse incentive for manufacturers to source cheaper illegal ivory in other places."

Speculating on scarcity

There are also worries that simply destroying stocks of ivory only encourages poachers to believe that scarcity will drive up prices, thereby giving a greater incentive to kill elephants.

"If we don't understand the role of speculators in the trade, the destruction could be counter productive in the long run," said Tom Milliken.

"But I think where we stand right now, the public relations role of these acts is symbolically a good thing."

The hope is that China can turn a corner on its demand for ivory - 30 years ago Japan was importing 500 tonnes of ivory a year, leading to 25,000 elephant deaths. Now it is using about 5% of that amount.

But if the middle class continues to grow, and education programmes are not successful in changing habits, Tom Milliken is worried that Chinese demand alone could see the elephant's extinction.

"There just aren't enough elephants remaining to sustain a constant growth in ivory demand in that country," he said.

And for some speculators, that is the optimum position.

If the elephants were wiped out, there would be large stockpiles of a scarce substance that couldn't be replaced.

And it's likely that if the elephants went, the restrictions on ivory sales would also go.

Derailing these macabre calculations will be critical in the survival of the species.

Follow Matt on Twitter, external.

- Published29 December 2011

- Published18 October 2013

- Published1 July 2013