Antarctic ice line patterns detected by Cryosat spacecraft

- Published

Alignment is evident on the large scale, such as in sastrugi, but also in the very micro-structure of the ice

The persistent wind blowing across the high Antarctic plateau sculpts striking waves and curves in the ice surface, and it seems their signature can be detected in satellite data.

Known as sastrugi, these features have the look of meringue or royal icing.

Most are too small to be photographed directly from orbit, but a satellite can discern their presence from the way they scatter a radar signal.

Europe's Cryosat spacecraft encountered this issue as it sought to measure changes in the height of the ice.

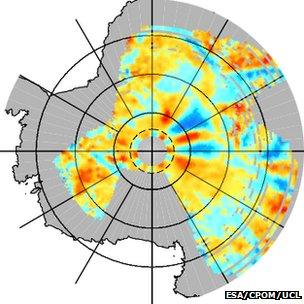

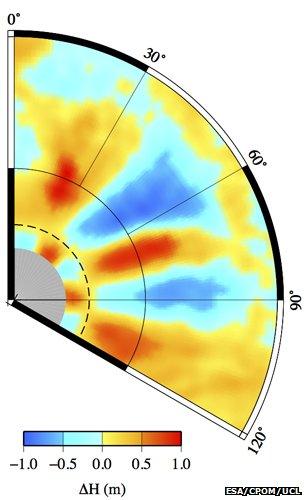

A distinct and very unusual pattern radiating from the South Pole was appearing in its maps.

At first, this caused some consternation at the European Space Agency (Esa) because it suggested the mission might have had a fault.

Radar data is used to monitor changes in the height of the ice

"The pattern was very pronounced and seemed to beat around the pole," explained Tom Armitage from the UK Nerc Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at University College London.

"There was a fair amount of alarm, I have to say, because it looked like nothing anyone had ever seen before.

"We wondered if something was wrong with Cryosat. Had we miscalculated the altitude? Was there a timing error, or a problem with the corrections we apply to the measurements?

"We had to do various experiments to eliminate all these possibilities," he told BBC News.

It turns out the pattern results from the way the polarised radar signal interacts with the ice surface and near-surface.

Antarctica is dominated by its strong katabatic winds, which run downhill from the interior towards the coast.

These winds blow the same way over prolonged periods of time, producing highly directional features in the ice.

Sastrugi are one consequence of this, but the preferred alignment affects also the very micro-structure of the snow pack and its crystal orientation.

Close up: A distinct and very unusual pattern is seen to beat away from the pole

This becomes apparent in the Cryosat maps because the spacecraft acquires its radar data at locations where its orbits cross over.

This means the satellite is sensing the directional quality of the ice slightly differently depending on whether it is flying from the north or the south.

Now that the scientists understand this effect, they can take account of it in their research, and it will have no impact on the monitoring of elevation changes in the Antarctic.

This has become a useful way to understand what is going on underneath the ice sheet, which can rise and fall when great masses of water gather in sub-glacial lakes and then suddenly flood away.

It might also now be possible to use the radar pattern in an entirely different way.

The effects of the wind on the ice sheet, such as sastrugi, eventually become buried, taking with them a record of the prevailing wind behaviour in the Antarctic.

By drilling through the ice and studying its layers, scientists have been able to reconstruct this activity stretching back over thousands of years. It is information that has been used to inform models of past atmospheric circulation.

Cryosat cannot see as deeply or resolve such fine details, but it is conceivable that the radar artifact could be used to investigate the stability of the wind field over more recent Antarctic history. And being a satellite, Cryosat could observe a wider area of the continent than just the point measurements offered by ice cores.

Cryosat is Esa's dedicated polar monitoring spacecraft

"It's an interesting idea. Cryosat's radar penetrates up to roughly 10m, so you would be sampling over a period of time, but nothing like as long as the ice cores," said Mr Armitage.

Dr Edward King is a glaciologist at the British Antarctic Survey.

"Sastrugi are beautiful things; there's no doubt about it," he told BBC News.

"The wind process that forms them is both an erosional one and a depositional one.

"They can vary from a few centimetres in height - and these are pretty ubiquitous over the Antarctic - up to true monsters that may be up to a metre-and-a-half high. And they can be absolutely rock hard; you can walk across them and leave no boot prints."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published11 December 2013

- Published16 December 2013

- Published20 September 2013

- Published11 September 2013

- Published13 February 2013

- Published24 April 2012