Organised crime sets sights on wildlife

- Published

Despite efforts to destroy ivory, criminals are becoming more organised, ingenious and dangerous

"We have seen more and more organised crime networks moving into the wildlife trade," says Davyth Stewart from Interpol, the international intelligence agency.

"Groups who have been traditionally involved in drug trafficking, fire arms and human trafficking are now moving onto wildlife."

It's clearly not a fair match: conservationists pitted against criminal gangs.

But the wildlife experts say it's a fight they have to take on.

They have gathered at the Zoological Society of London to tackle how to halt the rapidly growing trade in animals.

The backdrop to these crisis talks is bleak.

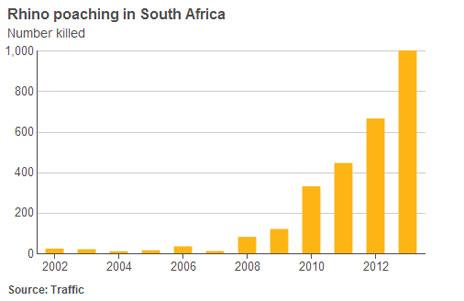

Thousands of rhinos, elephants, tigers and others have been slaughtered, becoming part of an illegal market that's worth an estimated $19bn a year.

Many criminals see it as low risk, high profit, says Mr Stewart.

"There is a lower risk of apprehension, it's unfortunate but law enforcement has not invested the resources in attacking wildlife crime as it has in other crimes," he explains.

"Even in courts the penalties are much lower. Just last year in Ireland, we saw two people arrested for smuggling rhino horns worth half a million euros. They received a 500-euro fine."

Demand and supply

John Sellar, the former chief of enforcement at Cites (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), says the focus of the battle should be shifted away from conservation towards the issue of criminality.

"It's about locking up the bad guys," he tells the conference. And the same tactics and intelligence currently used to fight narcotics and arms could be employed to stop animal trafficking.

"But the right people aren't in the room. Where are the judges, the customs officers, the police?" he asks.

Like other illicit trades, wildlife trafficking too involves kingpins who sit atop elaborate supply chains.

Poachers on the ground find and kill the animals, brokers move the product around in the country, exporters get it across international borders, sellers then make sure it gets to the right customers.

Corruption, says Naftali Honig, from the Project for Application of Wildlife Law for Fauna (Palf) in the Republic of Congo, is oiling the wheels of this criminal process.

He explains: "In terms of getting a proper deterrent and getting the wildlife trafficker prosecuted, corruption is our biggest problem. We're coming across bigger and bigger dealers and corrupt officials.

"And those cases are just extremely difficult - there's always a phone call, there's always a friend of a friend, there's always some reason why the case is being forgotten, minimised or even thrown out. It is very pervasive."

Amongst the many losses, though, there have been some victories.

In Bardia National Park in Nepal, wildlife officers have worked with local communities, and guns and weapons that were once used to kill tigers, elephants and rhinos were handed in voluntarily.

In Kenya, a new Wildlife Conservation and Management Act has been passed that means traffickers face stiff penalties or long sentences.

Advances in forensics are helping scientists to link wildlife products that have been seized back to the criminals.

However, many conservationists say the biggest breakthrough would be to halt the demand.

Because if people don't want the animal products, a market no longer exists, the criminals lose interest, the middlemen vanish and the poachers stop poaching.

The meeting at ZSL is discussing how to tackle a rapidly growing trade

Dr John Robinson, director of the Wildlife Conservation Society, says: "I think the big challenge right now is that the demand for wildlife products is skyrocketing.

"It is coming from the increased affluence in the Far East, especially in China."

Rhino horns are sold as medicines - marketed to cure anything and everything despite the fact they are made of keratin, the same stuff that forms our hair and fingernails.

Other animal parts, such as tiger pelts or elephant tusks are bought as status symbols, giving their owners an aura of wealth and power.

Dr Robinson says: "There are two steps to solving the demand issue, one is to make people aware that ivory, for example, comes from live animals and animals have to be killed to supply that ivory. And that is information not commonly understood in some parts of the world.

"And then once you understand those issues, you have to change people's behaviour."

Marketing and education, through social media or otherwise, are key, he says.

"I'm confident that once people are aware of what the issues are, we will see some significant change."

NGOs, who include the Zoological Society of London, Traffic, WWF, Wildlife Conservation Society, Fauna and Flora International, the Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, the IUCN, are feeding their findings from the conference into another meeting hosted by the UK government on Thursday.

They will be asking international leaders at Lancaster House to consider strengthening an international legal framework, establishing a co-ordinated effort on the ground to stop poachers, creating marketing and education programmes to halt demand, and they are asking for a zero-tolerance policy from industry towards animal trafficking.

They will be joined by Prince Charles and Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, who through The Royal Foundation are supporting the Unite for Wildlife campaign.

Ahead of the meeting, the US government has announced a national strategy for combating wildlife trafficking, which includes a blanket ban on the trade in elephant ivory.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external.

- Published11 February 2014

- Published11 February 2014

- Published9 February 2014