Can a Zen-like approach help countries with floods?

- Published

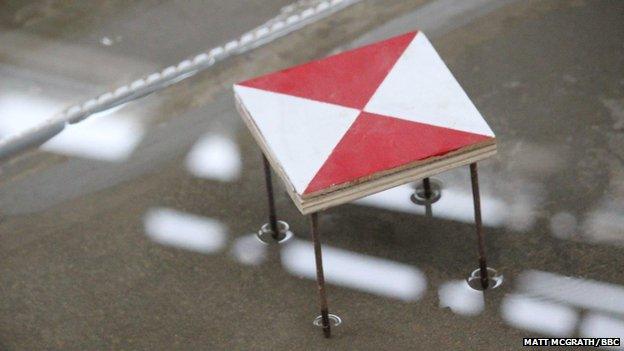

This wooden marker represents a school where 84 pupils and teachers lost their lives in the tsunami of 2011

Coping with increased risk of flooding in a changed climate is not just about money. BBC environment correspondent Matt McGrath reports from Japan, where philosophy is just as important as resources.

At a large government research facility in Tsukuba city, engineers have built a 30-sq-m replica of a meandering Japanese river.

At one point along the concrete shore, there's an unremarkable, small square of wood, with red and white triangles on top. But it is a constant reminder of the power of water to cause tragedy.

The wooden marker represents Okawa elementary school, where 84 pupils and teachers lost their lives in the terrible tsunami of 2011.

The model also highlights another piteous element of this disaster.

Okawa is close to the river but only a short distance from high ground. Sadly, the school itself had been designated an evacuation area in case of tsunami, and teachers led the children to an area near a river dyke rather than the hill behind the school.

For the engineers here in Tsukuba, the wooden square shows why their work really matters.

"We had not expected such a big tsunami wave in the past," says Dr Kazuhiko Fukami, research co-ordinator here at the National Institute for Land, Infrastructure and Management.

This replica of a meandering river is used to study flood risk

"We are now trying to establish how to predict such tsunami height along the river, more realistically."

Flooding caused by tsunamis is a mercifully rare event, but Japan has long had issues with rising waters. In 300 years, there were 130 flood disasters in the river Tone basin alone.

The Japanese, though, have not been slow to learn from such losses. Dams, levees and run-offs have been built. The Tokyo area has the world's largest flood diversion facility.

The country has become a world leader in flood risk management.

Just a few hundred metres from the river model site sits another large, warehouse-sized laboratory.

It's filled with constant noise of rushing water, flowing through plastic tubes and runways, as technicians test modifications to large-scale mock-ups of dams.

The work is being carried out under the auspices of the International Centre for Water Hazard and Risk Management (ICHARM).

"Around 80% of all the water-related disasters in the world happen in Asia," says Dr Minoru Kamoto, chief researcher at the centre.

"But recently because of climate change, water and disaster has become a big problem in all parts of the world."

The new report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is set to predict that by 2100, hundreds of millions of people will be affected by coastal flooding and displaced due to land loss.

This mock-up dam helps to model the impact of climate change scenarios

Dr Kamoto says there are good reasons to be concerned:

"If you are talking about the increase in CO2, the temperature rise will happen a few decades later. But already fluctuations of hydrological phenomena are happening," he says.

"These fluctuations and the gradual increase of the temperature may cause an acceleration of extreme flooding situations in the future. That is what we are really concerned about."

Coping with the threat of rising waters can take many forms. As well as large-scale infrastructure projects, like the ones being tested at ICHARM, simple steps can have real impact.

"In Bangladesh, there was a big cyclone 30 years ago where more than 100,000 people were killed," says Dr Kamato.

"But recently because of flood warnings and flood shelters, this has reduced the number of lives lost by orders of magnitude - before 100,000 or more, now 1,000 or less."

But the researchers at ICHARM say that as well as practical steps, a more holistic understanding of climate change is needed to really see the bigger picture.

"The disaster impact is increasing so much, this has nothing to do with climate change, it is a change of society," said the director of ICHARM, Prof Kuniyoshi Takeuchi, who believes growing populations and migrations to urban areas are very important factors behind the scale of disasters.

"The social system change is quite evident. In 2011 the flooding in Thailand was quite serious - but the impact went beyond Thailand to outside the region and to the global economy."

This view - that climate change is not isolated from the challenges of society - is reflected to a greater degree in the latest leaked draft of the IPCC report, which talks about "intersecting social processes" making people vulnerable.

The solutions, too, require a more thoughtful approach say the experts at ICHARM.

"If you talk about the philosophy of flooding, the philosophy of flood preparedness, we should remind ourselves that our ancestors have lived in such situations in the past, adapting to the nature at that time," says Dr Kamoto.

"We have to do the same thing, adapting to the modern situation.

"There are things that individuals can do, like helping your neighbours. When those disasters come, you have to be mentally and spiritually prepared for the vagaries of the danger."

Perhaps it's their long-term experiences with flooding that has helped the Japanese to adopt this Zen-like perspective on the future problems of a warming climate.

In the wake of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, there has been no rush to rebuild, as both governments and authorities realise that flood disasters on a hotter planet could be on a scale we have not yet experienced.

Back at the river model experiment, Dr Fukami says that consciousness has expanded.

"The tsunami was a trigger impact to change the mind about how to react against extreme events," he says.

"In the past we thought the possibility was very low and we don't have to consider extreme events. But our mind is now changing, and we have to be prepared."

- Published28 March 2014

- Published26 March 2014

- Published25 March 2014

- Published25 March 2014