Dark matter hunt: LUX experiment reaches critical phase

- Published

The experiment, in a gold mine in South Dakota, could offer the best chance of detecting dark matter

The quest to find the most mysterious particles in the Universe is entering a critical phase, scientists say.

An experiment located in the bottom of a gold mine in South Dakota, US, could offer the best chance yet of detecting dark matter.

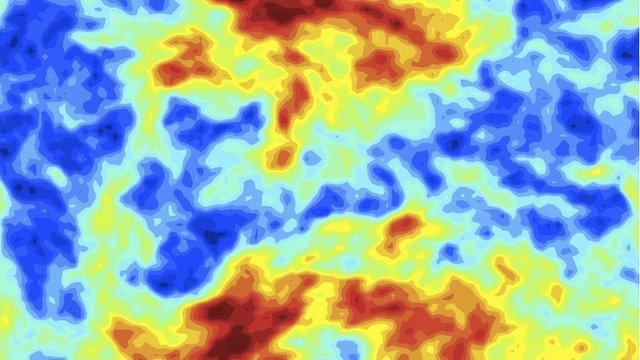

Scientists believe this substance makes up more than a quarter of the cosmos, yet no-one has ever seen it directly.

Early results from this detector, which is called LUX, external, confirmed it was the most powerful experiment of its kind.

In the coming weeks, it will begin a 300-day-long run that could provide the first direct evidence of these enigmatic particles.

Spotting WIMPs

Beneath the snow-covered Black Hills of South Dakota, a cage rattles and creaks as it begins to descend into the darkness.

For more than 100 years, this was the daily commute for the Homestake miners searching for gold buried deep in the rocks.

Today, the subterranean caverns and tunnels have been transformed into a high-tech physics laboratory, external.

Scientists now make the 1.5km (1-mile) journey underground in an attempt to solve one of the biggest mysteries in science.

"We've moved into the 21st Century, and we still do not know what most of the matter in the Universe is made of," says Prof Rick Gaitskell, from Brown University in Rhode Island, one of the principle investigators on Large Underground Xenon (LUX) experiment.

The LUX detector is located 3km underground - and could be our best hope yet of finding dark matter

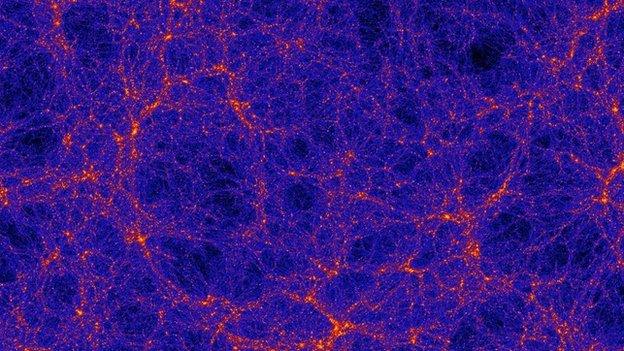

Scientists believe all of the matter we can see - planets, stars, dust and so on - only makes up a tiny fraction of what is actually out there.

They say about 85% of the matter in the Universe is actually dark matter, so called because it cannot be seen directly and nobody really knows what it is.

This has not stopped physicists coming up with ideas though. And the most widely supported theory is that dark matter takes the form of Weakly Interacting Massive Particles, or WIMPs.

Prof Gaitskell explains: "If one considers the Big Bang, 14bn years ago, the Universe was very much hotter than it is today and created an enormous number of particles.

"The hypothesis we are working with at the moment is that a WIMP was the relic left-over from the Big Bang, and in fact dominates over the regular material you and I are made of."

The Homestake gold mine, which has now been converted into a lab, is in the Black Hills of South Dakota

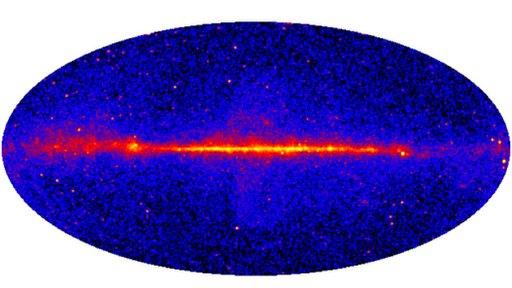

The presence of dark matter was first inferred because of its effect on galaxies like our own.

As these celestial systems rotate around their dense centre, all of the regular matter that they contain does not have enough mass to account for the gravity needed to hold everything together. Really, a spinning galaxy should fly apart.

Instead, scientists believe that dark matter provides the extra mass, and therefore gravity, needed to hold a galaxy together.

It is so pervasive throughout the Universe that researchers believe a vast number of WIMPs are streaming through the Earth every single second. Almost all pass through without a trace.

However, on very rare occasions, it is thought that dark matter particles do bump into regular matter - and it is this weak interaction that scientists are hoping to see.

The LUX detector is one of a number of physics experiments based in the Sanford Underground Research Facility that require a "cosmic quietness".

Prof Gaitskell says: "The purpose of the mile of rock above is to deal with cosmic rays. These are high-energy particles generated from outside our Solar System and also by the Sun itself, and these are very penetrating.

"If we don't put a mile of rock between us and space, we wouldn't be able to do this experiment."

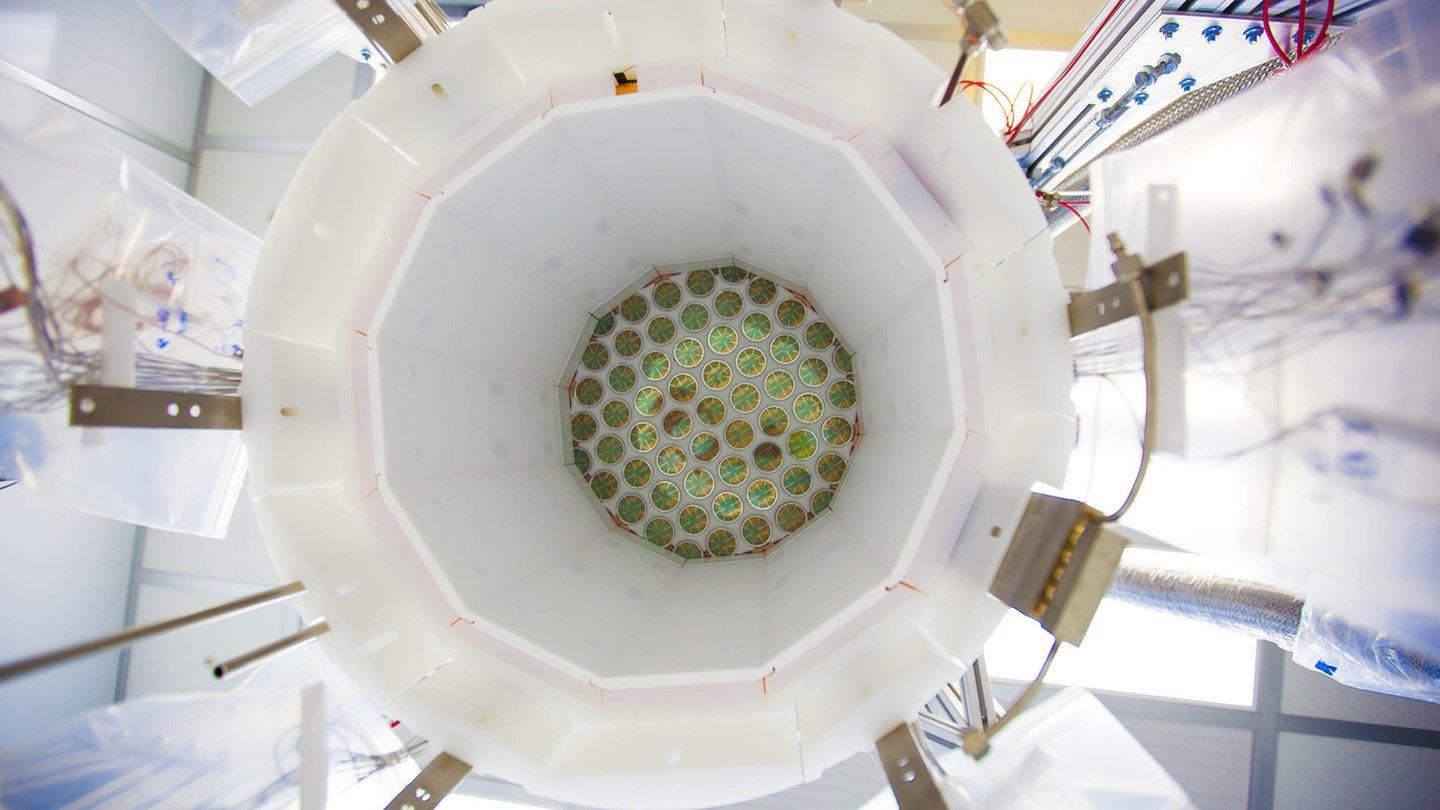

Inside a cavern in the mine, the detector is situated inside a stainless steel tank that is two storeys high.

The detector is in housed in a tank that is filled with purified water

This is filled with about 300,000 litres (70,000 gallons) of ultra-purified water, which means it is free from traces of naturally occurring radioactive elements that could also interfere with the results.

"With LUX, we've worked extremely hard to make this the quietest verified place in the world," says Prof Gaitskell.

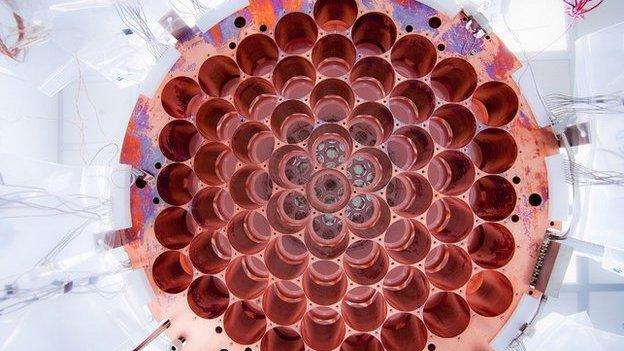

At the detector's heart is 370kg (815lb) of liquid xenon. This element has the unusual, but very useful, property of throwing out a flash of light when particles bump into it.

And detecting a series of these bright sparks could mean that dark matter has been found.

The LUX detector was first turned on last year for a 90-day test run. No dark matter was seen, but the results concluded that it was the most sensitive experiment of its kind.

Now, when the experiment is run for 300 days, Prof Gaitskell says these interactions might be detected once a month or every few months.

The team would have to see a significant number of interactions - between five and 10 - to suggest that dark matter has really been glimpsed. The more that are seen, the more statistical confidence there will be.

LUX uses light detectors called photomultiplier tubes to record any flashes of light

However, LUX is not the only experiment setting its sights on dark matter.

With the Large Hadron Collider, scientists are attempting to create dark matter as they smash particles together, and in space, telescopes are searching for the debris left behind as dark matter particles crash into each other.

Mike Headley, director of the South Dakota Science and Technology Authority, which runs the Sanford laboratory, says a Nobel prize will very probably be in store for the scientists who first detect dark matter.

He says: "There are a handful of experiments located at different underground laboratories around the world that want to be the first ones to stand up and say 'we have discovered it', and so it is very competitive."

Finding dark matter would transform our understanding of the Universe, and usher in a new era in fundamental physics.

However, there is also a chance that it might not be spotted - and the theory of dark matter is wrong.

Dr Jim Dobson, based at the UK's University of Edinburgh and affiliated with University College London, says: "We are going into unknown territory. We really don't know what we're going to find.

"If we search with this experiment and then the next experiment, LUX Zeppelin, which is this much, much bigger version of LUX - if we didn't find anything then there would be a good chance it didn't exist.

He adds: "In some ways, showing that there was no dark matter would be a more interesting result than if there was. But, personally, I would rather we found some."

Prof Carlos Frenk, a cosmologist from Durham University, says that many scientists have gambled decades of research on finding dark matter.

He adds: "If I was a betting man, I think LUX is the frontrunner. It has the sensitivity we need. Now, we just need the data.

"If they don't [find it], it means the dark matter is not what we think it is. It would mean I have wasted my whole scientific career - everything I have done is based on the hypothesis that the Universe is made of dark matter. It would mean we had better look for something else."

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published20 January 2014

- Published18 November 2013

- Published30 October 2013

- Published1 July 2013

- Published15 April 2013

- Published3 April 2013

- Published6 February 2013

- Published20 June 2012