Megacities contend with sinking land

- Published

- comments

Inundation of flood water in these cities is becoming a more significant problem

Subsiding land is a bigger immediate problem for the world's coastal cities than sea level rise, say scientists.

In some parts of the globe, the ground is going down 10 times faster than the water is rising, with the causes very often being driven by human activity.

Decades of ground water extraction saw Tokyo descend two metres before the practice was stopped.

Speaking at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly, researchers said other cities must follow suit.

Gilles Erkens from the Deltares Research Institute, in Utrecht, in the Netherlands, said parts of Jakarta, Ho Chi Minh City, Bangkok and numerous other coastal urban settlements would sink below sea level unless action was taken.

His group's assessment of those cities, external found them to be in various stages of dealing with their problems, but also identified best practice that could be shared.

"Land subsidence and sea level rise are both happening, and they are both contributing to the same problem - larger and longer floods, and bigger inundation depth of floods," Dr Erkens told BBC News.

Gilles Erkens: "Land subsidence has not had the attention given to sea level rise"

"The most rigorous solution and the best one is to stop pumping groundwater for drinking water, but then of course you need a new source of drinking water for these cities. But Tokyo did that and subsidence more or less stopped, and in Venice, too, they have done that."

The famous City of Water in north-east Italy experienced major subsidence in the last century due to the constant extraction of water from below ground.

When that was halted, subsequent studies in the 2000s suggested the major decline had been arrested.

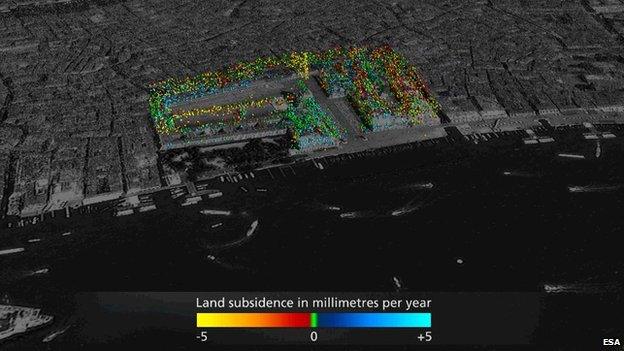

Pietro Teatini's research, external indicates that significant instances of descent were now restricted to particular locations, and practices: "When some people restore their buildings, for example, they load them, and they can go down significantly by up to 5mm in a year." How far they descended would depend on the type and compaction of soils underneath those buildings, the University of Padova researcher added.

Like all cities, Venice has to deal with natural subsidence as well.

Sea level rise and land subsidence are two halves of the same problem

Large-scale geological processes are pushing the ground on which the city sits down and under Italy's Apennine Mountains. This of itself probably accounts for a subsidence of about 1mm each year. But on the whole, human-driven change has a greater magnitude than natural subsidence.

Scientists now have a very powerful tool to assess these issues. It is called Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar. By overlaying repeat satellite images of a specific location, it is possible to discern millimetric deformation of the ground.

Archives of this imagery extend back into the 1990s, allowing long time-series of change to be assessed.

The European Space Agency has just launched the Sentinel-1a radar satellite, which is expected to be a boon to this type of study.

Satellite radar has become a powerful tool to follow land subsidence in cities

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published11 April 2014

- Published3 April 2014