EU launches flagship Sentinel satellite project to monitor Earth

- Published

A clean getaway for the Soyuz carrying Sentinel-1a

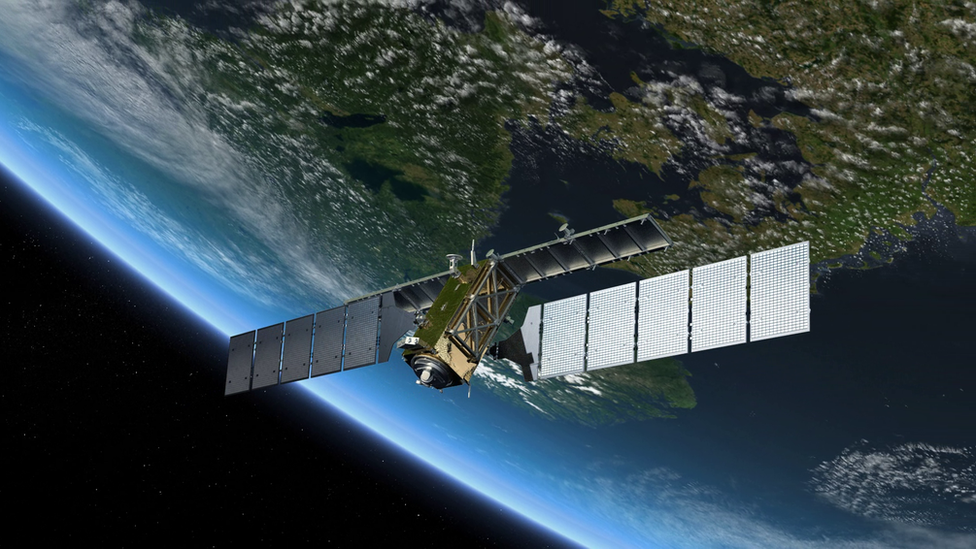

A Soyuz rocket has launched from French Guiana with the first satellite in the European Union's new multi-billion-euro Earth-observation programme.

The Sentinel-1a spacecraft has been put in orbit on a mission to map the planet's surface using radar.

It will be followed by a fleet of other satellites - also called Sentinels - over the next five years.

Brussels is describing its Copernicus programme, external as the biggest ever effort to characterise our world.

When the full satellite system is operational, it will be producing daily some eight terabytes of data to detail the state of Earth's land surface, its oceans and its atmosphere.

European nations have so far committed 7.5bn euros (£6.2bn; $10.3bn) to the project. But the vision for Copernicus is that it is unending - that every Sentinel satellite is replaced at the demise of its mission, ensuring there is continuity of information deep into this century.

"Once all the Sentinel satellites have been launched, the Copernicus programme will be the most efficient and fullest Earth-observation programme in the world," said European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso.

"This investment will allow Europe to establish itself at the forefront of research and innovation in a cutting-edge sector - namely, space. Many skilled jobs have been created and many more are yet to come."

The Soyuz carrying the first radar observer lifted clear of the Sinnamary launch pad on the Guianese coast at 18:02 local time (21:02 GMT; 22:02 BST).

The ride to an altitude of 699km took 23 minutes. A signal confirming a clean separation for Sentinel-1a from the rocket was received shortly afterwards.

Controllers at the European Space Agency's (Esa) operations centre in Darmstadt, Germany, must now commission the spacecraft.

The first hours will be spent sending commands to the satellite to get it to unpack its solar wings and the panels of its radar instrument.

These were all folded to fit inside the Soyuz. The task should be complete by early morning on Friday, European time.

Formal entry into service is expected in about three months' time, although it is likely that the platform will start imaging the Earth as early as next week to begin the process of instrument calibration.

Radar has myriad uses, from monitoring shipping lanes for pollution or icebergs, to mapping land surfaces to track deforestation or the performance of rice production.

However, a key use for Sentinel-1a will be in disaster response.

Radar is especially good at detecting the extent of flood waters, and this type of image is also regularly employed following major earthquakes to assess the damage to infrastructure.

Sentinel-1a will test a new laser-based data-relay system that will be at the heart of the Copernicus system. The technology, developed by German engineers, will not only handle more data than traditional downlinks but speed the information's receipt on Earth.

"The laser terminal will reduce the access time to data from hours to minutes," explained Esa Director General Jean-Jacques Dordain.

"In the case of natural catastrophes, saving time will save lives."

Five further Sentinel-themed missions with different types of sensors should be in orbit by 2019.

The idea is that the satellites are flown as pairs so that the revisit periods to locations on the Earth to take the next swath of images are kept as short as possible.

Thus, a Sentinel-1b will be launched next year. Sentinels 1c and 1d will be sent up to take over observing duties when it looks like 1a and 1b might be about to fail.

In this way, Copernicus and its dedicated Sentinels will start to build continuous, cross-calibrated, long-term datasets.

These will be a boon to climate studies. But the EU hopes the data will prove to be a powerful tool also to help design and enforce community-wide polices, covering diverse areas such as fish stocks management, air quality regulation, and keeping track of waste disposal practices.

Copernicus is the EU's second major space project after the Galileo satellite-navigation system, which is also in the process of roll-out.

As with "Europe's GPS", Esa has been engaged as the procurement agent, designing the satellites' requirements and contracting with industry to produce them.

Sentinel-1a's construction has been led by Thales Alenia Space (Italy/France), with its C-band radar instrument and electronics coming from Airbus (Germany and UK).

Radar to forecast flooding

The UK authorities made extensive use of satellite imagery over the wet winter

Radar scatters away from a satellite very efficiently over water surfaces

This makes it very easy to see those areas that are flooded

Radar is already used to assess the extent of flood inundation

Fast-return Sentinel data will permit flood forecasting as well

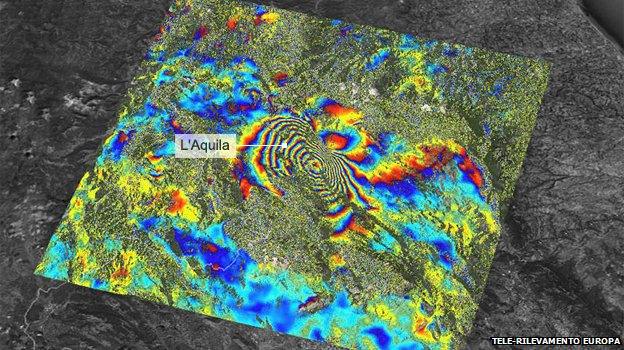

Radar to study earthquakes

Radar interferometry reveals fault locations. The L'Aquila quake damaged a satellite component factory

Radar imagery is used to monitor how the ground moves over time

In cities, series of pictures can reveal areas subject to subsidence

In quake zones, before and after imagery will pinpoint ruptured faults

Sentinel-1a's production was delayed by the L'Aquila tremor in 2009

Sentinel data super-highway

Sentinel-1a will test the laser-link technology needed for Europe's rapid data-relay system

Current satellites dump data when passing over ground stations

This will be too slow for the expected terabytes of Sentinel data

A European Data Relay System is being devised, to use laser links

Sentinel data will be bounced off overhead satellites in near real-time

Sentinel-1a will be followed into orbit by a fleet of other sensors

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 April 2014

- Published17 January 2014

- Published25 July 2013

- Published11 February 2013

- Published8 December 2011