Greenland's long glacier fjords point to higher seas

- Published

Greenland has more than 200 major outlet glaciers along its periphery

Greenland's ice sheet may be more vulnerable to melting than previously thought, say scientists.

A new study has reassessed the shape of the great fjords down which glaciers drain to the ocean.

It finds them to be far deeper and to stretch further back inland than was recognised in earlier research.

Dr Mathieu Morlighem told the Nature Geoscience journal, external that this could expose the glaciers to more prolonged erosion by warm seawaters.

"We know that many of these Greenland glaciers are accelerating and that their fronts are retreating because of the action of warmer ocean waters," he said.

"And because we now know these canyons are far longer than we thought, it means the ice forms can retire much further back, before rising on to land where they won't be in contact with the ocean anymore."

The usual way to map the thickness of glaciers and the position of the underlying rockbed is to make surveys with airborne ice-penetrating radar.

But acquiring such data sets is both expensive and difficult.

Even in those locations where radar has been used, the rugged terrain under the ice can often give a very cluttered picture.

And in places where melt water sits on top of the glacier, the radar pulse is simply deflected away from the ice body.

Consequently, our knowledge of the true shape of the 200-plus drainage channels around the edge of Greenland has been sketchy.

Dr Morlighem and colleagues from the University of California at Irvine, external took a different route with their novel "mass conservation algorithm".

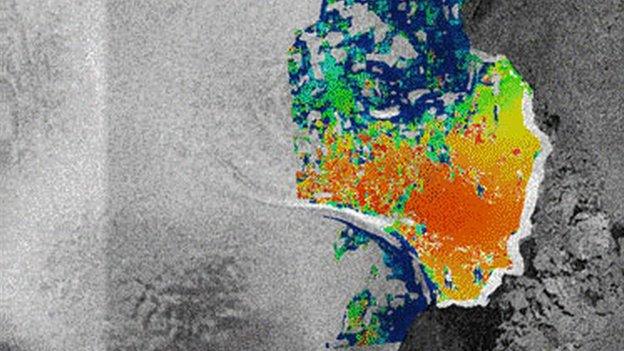

"For a given region of interest, I know what's coming in (snow fall), what's coming out (surface melt), and where the ice goes (ice motion derived from satellite [measurements])," the scientist explained.

"With these datasets I can calculate the ice thickness everywhere for the region of interest at a horizontal resolution that is comparable to the ice motion data (400m).

"I use ice-thickness data from airborne radar soundings to constrain the calculation of ice thickness (I want the calculated ice thickness to match the measurements along the flight lines where they were collected). To get the bed topography, I subtract the calculated ice thickness from a high-resolution surface topography dataset."

The approach reveals a number of previously unknown glacial valleys where the ice is grounded several hundred metres below sea level for many tens of km inland from the Greenland coast.

"Older models predicted that these glaciers would soon retreat on to higher ground and would stabilise, and so the contribution to sea-level rise from the Greenland ice sheet would be limited," said Dr Morlighem.

"But the problem is that these models were based on rockbed topography that was not accurate enough. With our new bed topography, we can expect the predictions for the Greenland ice sheet's contribution to sea-level rise to be changed."

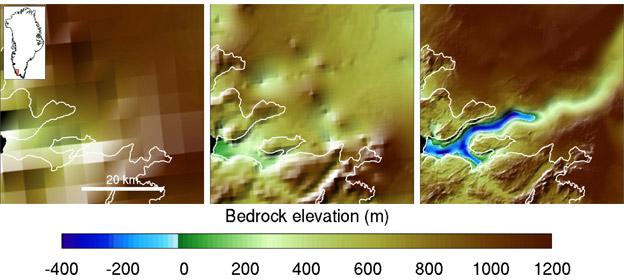

The graphic shows the evolution of the techniques to determine the shape of fjords, from 2001 (L), 2013 (C) and the new UC Irvine approach (R). Modelling possible future change requires good bedrock information

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published4 February 2014

- Published22 December 2013

- Published29 August 2013

- Published19 May 2014

- Published8 May 2014

- Published30 April 2014