Is Obama's climate 'regime change' unstoppable?

- Published

- comments

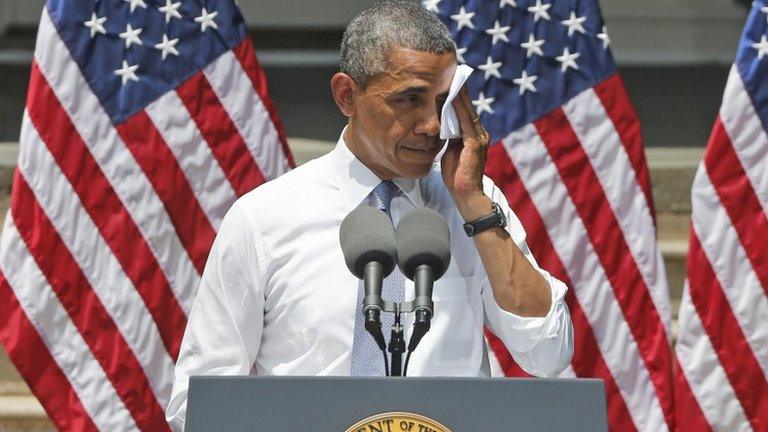

The EPA's Gina McCarthy outlined the proposals on emissions from existing power plants

"It is not just about disappearing polar bears and disappearing ice caps," said Gina McCarthy, head of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as she outlined the heavily-trailed Clean Power Plan proposal.

Cutting carbon emissions by a third by 2030, she said, was about "protecting our health and protecting our homes".

President Obama's new plan is not just taking aim at America's hearts and minds, he's going for the lungs as well.

Children with asthma will benefit from the new regulations to clean the air, the EPA chief said.

It is not about the theoretical impact of rising temperatures in far away places. This is a smart thing to do, supporters say, even if the planet wasn't at stake.

"It is a recognition on behalf of the administration that this is a personal issue," said David Wasskow from the World Resources Institute.

"It is not something abstract, somewhere else, but in fact is directly linked to the lives that people are leading."

Wrapping the issue of carbon cuts in the health of the nation is just one of the ways that the White House hopes to deliver what some observers are calling the most significant climate regulations in US history.

Another important observation is the size of the cuts that the President hopes to achieve. Reducing carbon emissions by a third by 2030 sounds like a lot, but in fact the US is already a long way down the track without any restrictions on existing power plants.

"Right now US emissions are down a little over 15% from 2005," said Alden Meyer, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, a long time observer of the international climate negotiations.

Each state will have to draw up a plan to curb carbon from the power sector

"From a combination of efficiency gains, renewable growth and a switch to natural gas, we're already about half way to the new 2030 goal."

To get the rest of the way, the EPA will now set state-specific targets. While the federal government will decide the number, it will be down to each state to meet it through any combination of less carbon intensive fuels, greater efficiency or carbon trading.

This flexibility could be seen as a weakness. Some critics believe that by giving states the option to compensate for what goes on "inside the fence" of a power plant with actions outside it, the EPA is moving into uncharted legal territory and it is certain to be tested in courts.

But Dr Dallas Burtraw from the conservation group Resources for the Future believes this flexibility is a strength. The way the regulations have been drawn up means that even if the courts bar one aspect, the rest still stands.

"If a court came in and said you can't account for energy efficiency because it is not verifiable or whatever, that might get erased but the rest of the rule might still stand we believe."

A critical point, according to Dr Burtraw is the timing. As each state has to draw up its own plan, it could be two years before they are finalised.

"There is not really anything for the lawyers to put their teeth into until the state plans are complete, and these rules will be quite far in their development before they are legally challengeable," he says.

He says that today's "regime change" on climate will alter the whole investment climate.

Utilities which have to decide on new power plants in the next two to three years will have to take a risky gamble that the rules will be struck out, or put their money in low carbon technology.

"The Clean Air Act is an amazing institution, it is like a freight train, slow but hard to stop, there will be blows and setbacks, but the act will be unstoppable," he says.

There has been much praise for the step from many observers who believe that it really will invigorate the moribund international climate negotiating process. They argue that countries like India and China will now have to react to this concrete step from the US.

Others are not so sure.

"I think it gives a little momentum to the administration to show that they are serious," says Alden Meyer.

"But negotiators I have talked to are very aware that the President is going into his last two years, people are beginning to ask how durable is this, is it something the next President will carry forward?

"It strengthens his credibility, but it is not like it is going to change all the dynamics and lead us to the promised land."

"It is going to be helpful, but not transformational."

Follow Matt on Twitter., external

- Published20 September 2013

- Published25 June 2013

- Published10 July 2011