Europe's Gaia telescope grapples with stray light

- Published

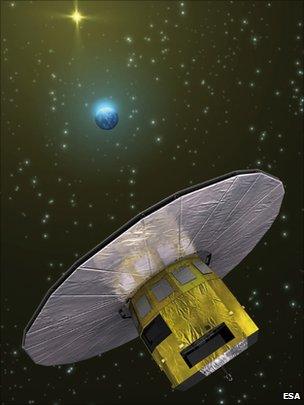

Gaia uses a 10.5m disc to shield its dual-telescope mechanism from the light and heat of the Sun

The orbiting Gaia telescope will lose some performance because stray light is getting inside the observatory, the European Space Agency (Esa) says.

But the impacts are likely to be very small, scientists believe, and the expectation is that all the mission's chief objectives will still be met.

Most of the unwanted light appears to be creeping around the giant shield Gaia uses to shade itself from the Sun.

The "pollution" makes it harder for the observatory to see the faintest stars.

"I must say this is not a major problem," said Esa's Gaia project manager, Giuseppe Sarri.

"The point is the spacecraft is doing very well in terms of everything is working, and now we're focussing on the things we want to improve.

"We were expecting to get some stray light but the fact is, it is larger than we predicted," he told BBC News.

Gaia was sent into orbit in December to do astrometry on a billion stars - to map their precise positions, distances and motions.

Telescope tent

This huge sample should provide the first true picture of our Milky Way Galaxy's structure.

As is normal after launch, the observatory was immediately put through a period of complex systems check-out and instrument calibration.

Engineers noticed early on that unexpected light was getting inside the big tent covering the satellite's dual telescope mechanism.

Modelling indicates most of it is sunlight being diffracted around the observatory's 10.5m-wide sunshield.

But further analysis suggests there is likely also some additional component - probably the general diffuse light on the sky itself.

Gaia - The discovery machine

Gaia will make a very precise 3D map of our Milky Way Galaxy

It is the successor to the Hipparcos satellite which mapped some 100,000 stars

The one billion to be catalogued by Gaia is still only 1% of the Milky Way's total

But the survey's quality promises a raft of discoveries beyond just the star map

It will find new asteroids and planets; It will test physical constants and theories

Gaia's sky map will be the reference to guide future telescopes' observations

The effect is certainly a nuisance because it makes it more difficult for Gaia to discern the least bright objects.

It was the mission's aim to measure the positions of all stars down to magnitude 20 (about 400,000 times fainter than can be seen with the naked eye).

The stray light means about 40% of the accuracy of those measurements at this lowest magnitude will be lost.

Backwards and forwards

On the upside, it should be possible to get some of the performance back if Esa agrees to extend the mission and additional data can be taken.

And it is true to say that most of Gaia's science will be done at magnitude 15 (4,000 times fainter than the naked eye limit) and brighter, which is unaffected.

Where the pollution issue may be felt more keenly is in determining the motions of stars towards or away (radial velocity) from the satellite.

This information will have a number of applications but will be used to help make a 3D movie of the galaxy - to run forwards to see what happens millions of years into the future, and backwards to reveal how the galaxy was assembled in the deep past.

Gaia was hoping to get radial velocity data for about 150 million of the brightest stars.

It involves taking the light from a star and spreading it out into its component colours for analysis. For the faintest objects in the targeted sub-set of stars, this process again becomes much harder with stray light.

The Gaia team thinks with some smart techniques it can recover some of the performance loss, but as it stands the mission may get radial velocity measurements now on only about 100 million stars.

"We say only about 100 million stars - that's still pretty spectacular," said Prof Gerry Gilmore, a Gaia scientist from the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University, UK.

"We don't actually know how many stars there are in the sky at the magnitudes needed to do the radial velocity measurements," he added.

"We had a guess that it was 150 million but that could be wrong by a factor of two; so it's quite possible there are a lot more stars out there [we can still measure].

"Gaia is the first ever high spatial resolution survey and so until Gaia has scanned the sky we won't know what's on the sky."

.jpg)

Large sections of Gaia's telescope mechanism were constructed out of silicon carbide

Engineers are also tracking an issue with what they call the "basic angle".

Part of Gaia's measurement strategy requires it to look at two parts of the sky at the same time to lock a frame of reference.

This is why it carries two telescopes held rigidly at an offset angle of 106.5 degrees. Great effort was put into making sure this basic angle was absolutely stable, with many components being constructed out of stiff silicon carbide as a consequence.

But a vanishingly small flexure is being detected - fractionally beyond what had been anticipated.

The team believes, though, it can nullify any impacts if the behaviour can be properly characterised.

"It's all nuisance stuff. Depending how you count it, there are about 500 critical components on Gaia and they're all working fine," said Prof Gilmore.

"Yes, it's complicated; yes, there are things we don't fully understand yet; but there's no reason to believe Gaia won't be a triumph."

Mr Sarri added that after the long commissioning process, the telescope was now ready to gather data continuously.

"In the last week, we had an informal handover and it's been working already in science mode on occasions. But now we will move into a period of 28 days of uninterrupted operation," he told BBC News.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published6 February 2014

- Published19 December 2013

- Published28 November 2013

- Published21 August 2013

- Published8 March 2013

- Published10 October 2011