Shuttle diplomacy in climate countdown

- Published

The aim is for a deal limiting greenhouse gases

A senior British minister is once again launched on a long-haul high-carbon mission of shuttle diplomacy in the cause of tackling climate change.

The target is to try to land an international deal on limiting greenhouse gases at what is billed as a major summit in Paris in late 2015.

In climate terms, Paris has become the new Copenhagen, the next venue for another push for a global agreement following the failed attempt in Denmark five years ago.

As with the countdown to every global gathering of this kind, expectations are mounting and the smallest detail of phrasing or policy from key players is seized on as a sign that maybe, this time, perhaps, some cautious hope is justified.

Buoyed by a trip a fortnight ago to Washington - where President Obama recently announced his plan to limit emissions for power stations - Ed Davey, the Energy and Climate Change Secretary, arrives in China on Monday for his second major visit there and he will then fly on to India.

China, the US and India are the world's top three emitters - so they are fundamentally important to any agreement.

Guarded optimism

Mr Davey was not in the job at the time of the chaotic scenes in Copenhagen in December 2009 so he does not carry the wounds of that event and, to someone who was there, he sounds surprisingly upbeat.

So, I ask, is he genuinely optimistic that something might come out of all this?

"I'm more optimistic than I thought I'd be," he says.

"I think there's a desire in many capitals to do a deal - there's been a real shift.

"People are now thinking about what'll be in a deal not 'will there be a deal?'"

Given the US Senate has never been supportive of a climate treaty and that China and India have long argued that too many of their people are living in poverty to contemplate any action on emissions, how does the minister come to this view?

First, The US. Mr Davey's take is that Washington's new power station plan reflects a bolder White House prepared to use executive authority to bypass Capitol Hill.

"They are really motoring on this," he says.

The administration is also pushing for more rules on energy efficiency on a range of products while generating publicity about extreme weather.

This is a new more proactive policy intended to try to win votes.

"And if America, the second biggest emitter, is changing that's seismic."

China challenge

Next, China, which has traditionally resisted any attempt to include it in international limits on greenhouse gases.

Mr Davey points to comments by the Chinese chief negotiator Xie Zhenhua last week.

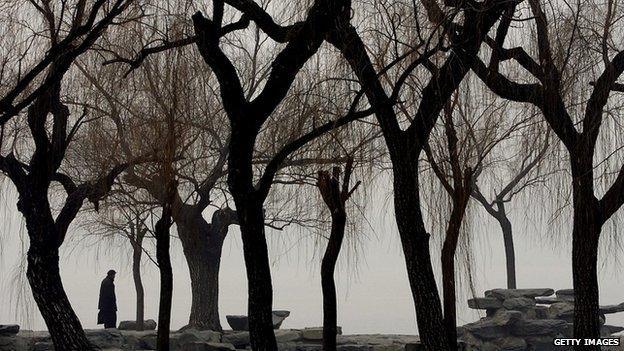

Air pollution is a big problem in China

Any statement by an official this senior is guaranteed to prompt a flurry of speculation - some grounded, some not - and this was no exception.

But Mr Xie's use of the words "peaking year" does seem to suggest that Beijing is contemplating a target date when its emissions will cease their rapid and massive climb.

If that does happen - possibly next year - it would a huge step.

Other factors shaping China's policy include air pollution, a scourge of Chinese cities, and a recognition of the vulnerability of coastal cities and supplies of key imports.

The Communist Party's term "ecological civilization" is seen as an official stamp on the need for a green approach.

Mr Davey is also heartened by new figures on China's use of coal. Instead of rising by 10% a year, coal use is now only increasing by 5%.

That does not mean less coal is being burned, only that the year-on-year growth in coal use has become smaller.

India is reliant on fossil fuel imports

This counts as success in the often strange world of climate diplomacy, where the smallest straws in the wind can acquire huge significance.

So what about India? Isn't the newly-elected Prime Minister vocally committed to driving up growth rather than driving down emissions?

Here Mr Davey highlights Narendra Modi's time running Gujarat when there were huge investments in solar power and how he's "been making some very encouraging noises".

Concern, he says, about the scale of India's imports of fossil fuels may foster an interest in homegrown low-carbon energy.

Finally, Europe, which is in the midst of fraught negotiations on a future EU-wide target.

The European Commission wants a target of a 40% cut in emissions by 2030.

Britain is pushing for 50% provided there's a deal at Paris. Poland, which is almost totally reliant on coal, is among countries holding out.

A decision is due in October.

So where does this leave us?

Hope and realism

By next March, we'll get a sense of likely progress.

By then all countries have promised to submit something called an intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) - a diplomatically-acceptable phrase describing national plans for emissions.

Mr Davey tries to balance hope and realism:

"Is political momentum going better than in the past?

"Yes. Obama is in his final term, China has got new leadership, India has got a new government, Europe is staying the pace and that's quite a good mix.

"Am I saying there'll definitely be a deal? Am I saying there's definitely going to be ambition - I have no idea…"

Sitting in the minister's office, listening to these words, I recalled hearing a similar narrative five years ago.

Back then, there was a long and perfectly logical list of reasons why the different elements of a global jigsaw would fit together.

But then came the summit in Copenhagen.

What chance Paris?