Giant laser observatory makes progress

- Published

The first generation of Ligo failed to find evidence of gravitational waves

The Advanced Ligo instrument, a laser "ruler" built to measure the traces of gravitational waves, is progressing at amazing speed, scientists say.

The first generation of Ligo, external, which ran between 2001 and 2010, saw nothing.

Over the last four years scientists have designed a more sensitive detector that achieved "full lock" in June this year, earlier than planned.

Researchers reported that the new one is already 30% more precise and will start scanning the sky in summer 2015.

Ligo (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) operates in two sites in the US, one in Livingston, Louisiana, and another one in Hanford, Washington.

Space ripples

"In June we reached this state that we call 'locking', where the entire system is switched on and behaves for a short time, 10 minutes or so, as predicted it should do in science mode," said Prof Andreas Freise from the School of Physics and Astronomy of the University of Birmingham during the British Science Festival, external.

Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space and time that propagate across the Universe like sound waves do after an earthquake.

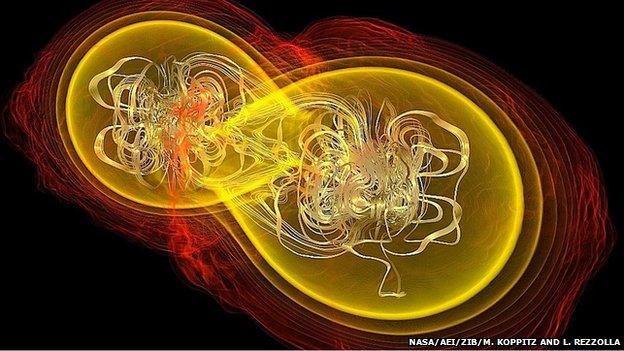

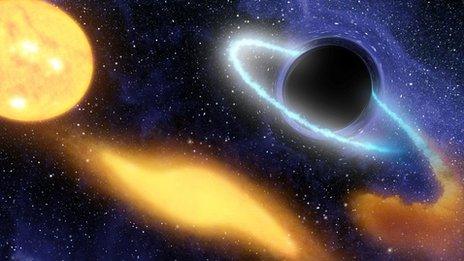

But in this case, the sources of the "tremors" are very energetic events such as supernovas (the explosion of a dying star), fast spinning neutron stars (very dense and compact stars), or the collision of black holes and neutron stars orbiting close to each other.

With Ligo's current precision, the interferometer should be able to detect gravitational waves coming from neutron star and black hole binary systems 27 megaparsecs (about 88 million light-years) away from us.

Researchers are still working on the intricate optical system and detectors within Advanced Ligo to gradually increase the precision.

"The target is to reach [a distance of] 200 megaparsecs… which is a factor of 10 better than the old detector," explained Prof Freise.

Gravitational waves are thought to emerge from energetic events such as the collision of two neutron stars

Augmenting the distance by a factor of 10 means that Ligo will scan a volume of space 1,000 times larger than before.

"Advanced Ligo will be sensitive to a factor of 1,000 in the volume that we were observing with initial Ligo, and that is the sphere of volume where we expect to see a few gravitational waves," added Prof Alberto Vecchio also from the School of Physics and Astronomy of the University of Birmingham.

Ligo observatories operate by beaming a high power laser into a splitter that divides the beam into two parts. Each part is then directed towards two 4km tunnels perpendicular to each other.

A mirror at the end of the tunnels reflects the rays back into a detector where they are recombined.

Since both tunnels are equally long, when the two halves meet in the detector the signal shows no pattern. But this is not the case if a gravitational wave were passing through the Earth.

"When [the gravitational waves] reach Earth they distort space and time. In particular, they will change the separation of the mirrors," explained Prof Vecchio.

"Over 4km, a decent gravitational wave that we can detect creates a change of less than a thousandth of the size of the nucleus of an atom."

This minuscule variation in the space between the mirrors will produce a distinct pattern from which the properties of the gravitational waves can be inferred.

Profound observation

The team at the University of Birmingham has been involved in Ligo since 2000, leading the development of technology and hardware, and the tools for the analysis of the scientific data.

The main improvements in Advanced Ligo included an upgraded suspension system of the mirrors to make them as stable as possible, a more powerful laser, and a change in the optical elements to accommodate the laser's extra power.

Although the former Ligo instruments did not detect any signature in its 10 years of observation, researchers think that with the upgrade, Advanced Ligo will be able to detect at least one gravitational wave in its lifetime.

Prof Vecchio said that the most pessimistic prediction is that "Ligo will deliver one detection over five years".

"Reasonable predictions tell you many events per year and there are optimistic ones that tell you a hundred or a thousand. We just don't know."

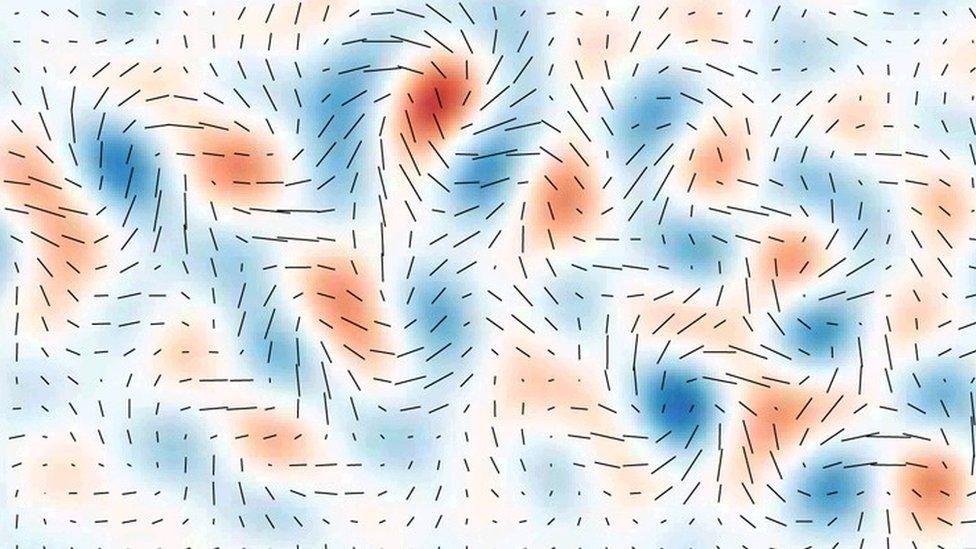

Ligo will complement rather than compete with the results of the Bicep2, external and Planck, external experiments, as it is tuned to look at much shorter wavelengths.

The implications of detecting gravity waves are profound from a scientific point of view.

Prof Freise said: "There are two aspects. One is testing the theory of gravity, but I think the more interesting for me is for astronomy.

"We are tapping into the unknown here, so we will get a new signal that may tell a lot of people in astronomy that they were wrong. And that's what I am after."

- Published3 July 2014

- Published20 June 2014

- Published7 November 2011

- Published18 March 2014