Microscope work wins Nobel Prize in Chemistry

- Published

The technique has extended the resolution of light microscopes

The 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to a trio of researchers for improving the resolution of optical microscopes.

Eric Betzig, Stefan Hell and William Moerner used fluorescence to extend the limits of the light microscope.

The winners will share prize money of eight million kronor (£0.7m).

They were named at a press conference in Sweden, and join a prestigious list of 105 other Chemistry laureates recognised since 1901.

The Nobel Committee said the researchers had won the award for "the development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy".

Profs Betzig and Moerner are US citizens, while Prof Hell is German.

Committee chair Prof Sven Lidin, a materials chemist from Lunds University, said "the work of the laureates has made it possible to study molecular processes in real time".

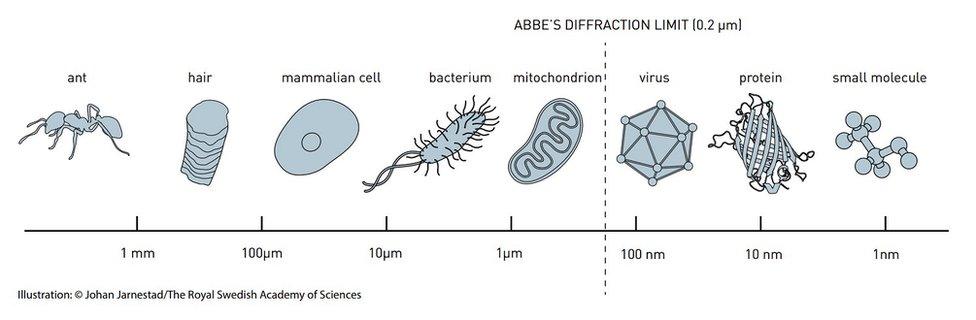

Optical microscopes had previously been held back by a presumed limitation: that they would never obtain a better resolution than half the wavelength of light.

This assumption was based on a rule known as Abbe's diffraction limit, named after an equation published in 1873 by the German microscopist Ernst Abbe.

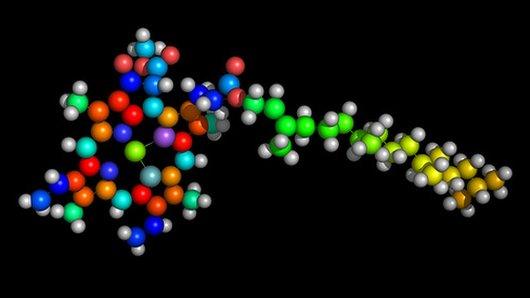

This year's chemistry laureates used fluorescent molecules to circumvent this limitation, allowing scientists to see things at much higher levels of resolution.

From left: Eric Betzig, Stefan Hell and William Moerner

Their advance enabled scientists to visualise the activity of individual molecules inside living cells.

Addressing the news conference in Stockholm, Prof Hell, from the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Germany, explained: "I got bored with the topic; I felt this was 19th century physics. I was wondering if there was still something profound that could be made with light microscopy. So I saw that the diffraction barrier was the only important problem that had been left over.

"Eventually I realised there must be a way by playing with the molecules, trying to turn the molecules on and off allows you to see adjacent things you couldn't see before."

Previous winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

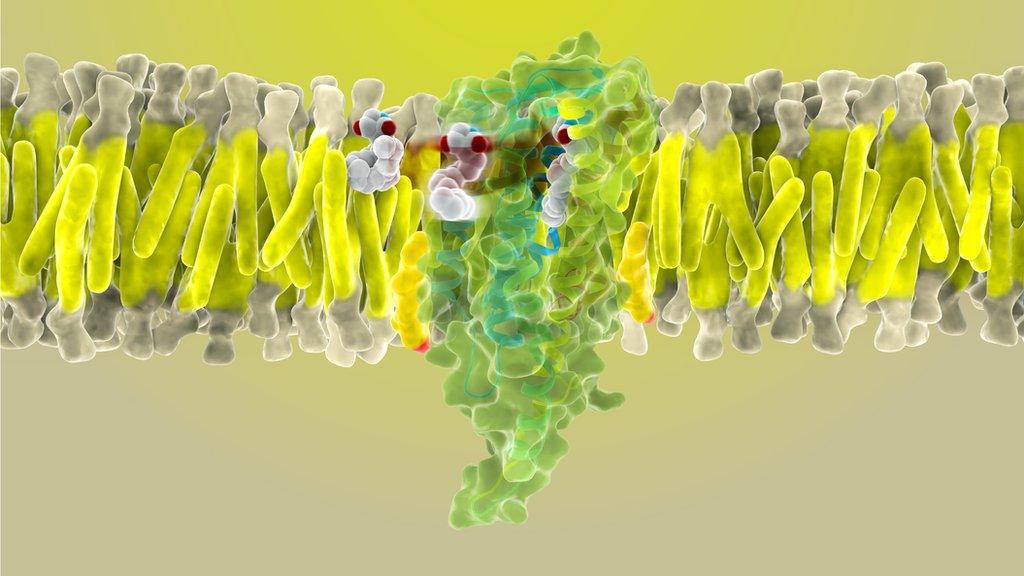

The 2012 prize recognised research on crucial biological molecules called G-protein coupled receptors

2013 - Michael Levitt, Martin Karplus and Arieh Warshel shared the prize, for devising computer simulations of chemical processes.

2012 - Work that revealed how protein receptors pass signals between living cells and the environment won the prize for Robert Lefkowitz and Brian Kobilka.

2011 - Dan Schechtman received the prize for discovering the "impossible" structure of quasicrystals.

2010 - Richard Heck, Ei-ichi Negishi and Akira Suzuki were recognised for developing new ways of linking carbon atoms together.

2009 - Discovering the structure and function of our cells' "protein factories", external, earned the chemistry Nobel for Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas Steitz and Ada Yonath.

Bypassing Abbe's physical limit of 0.2 micrometres means that the optical microscope can now peer into the nanoscopic world.

Commenting on the announcement, Prof Thomas Barton, president of the American Chemical Society, told BBC News: "On my level, the most impressive thing is to look at small molecules, to look at viruses in an atomic-resolved fashion.

"Also... to be able to look at living things and not to have to sacrifice them and look at them in a vacuum after sacrificing them as we do with transmission electron spectroscopy.

"It's incredible what you can do now. On my timescale, if you had suggested being able to look at something on a one nanometre scale - an atomic scale - 50 years ago, you'd have been laughed out of the room."

The Royal Society of Chemistry's president, Prof Dominic Tildesley, commented: "Super-resolution fluorescence spectroscopy is now enabling scientists to peer inside living nerve cells in order to explore brain synapses, study proteins involved in Huntington's disease and track cell division in embryos - revealing whole new levels of understanding as to what is going on in the human body down to the nanoscale.

He added: "Both involving light and both having their foundations in chemistry and physics, the parallels between today's Chemistry prize and yesterday's Physics prize highlight the truly interdisciplinary nature of science."

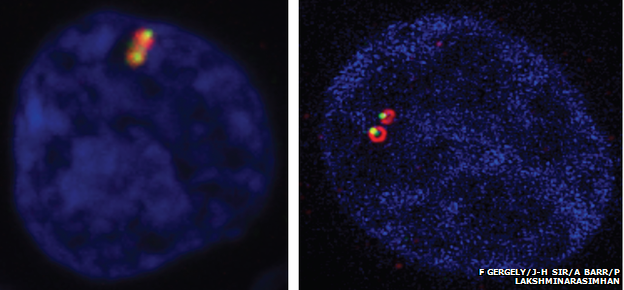

Images like this one, showing a cell nucleus about 0.006mm across, are vastly improved by super-resolution imaging; DNA is shown in blue and the "diamond rings" are tiny structures called centrosomes

The Nobel Prize rewards two separate approaches to the same principle. One is called stimulated emission depletion (Sted) microscopy, which was developed by Prof Hell in 2000.

The other is single-molecule microscopy, which was devised by Prof Betzig, of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Ashburn, US, and Prof Moerner, from Stanford University in California, whilst working separately.

Dr Stefanie Reichelt, head of light microscopy at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, uses these techniques in her work and was thrilled to hear they had been recognised by the Nobel.

"It's just changed so much in science - it's really beautiful," she told the BBC. "It opened up so many new fields and questions.

"Going down to the resolution limit, where you can see proteins interacting, DNA unfolding - if you go down to that level and you can watch this in live cells, that's such a leap forward. You almost don't need biochemistry anymore! Biochemistry is more abstract, because you have solutions and tubes and you deduce what is happening from that."

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published1 March 2011

- Published9 October 2013

- Published10 October 2012