Giant kangaroos 'walked on two feet'

- Published

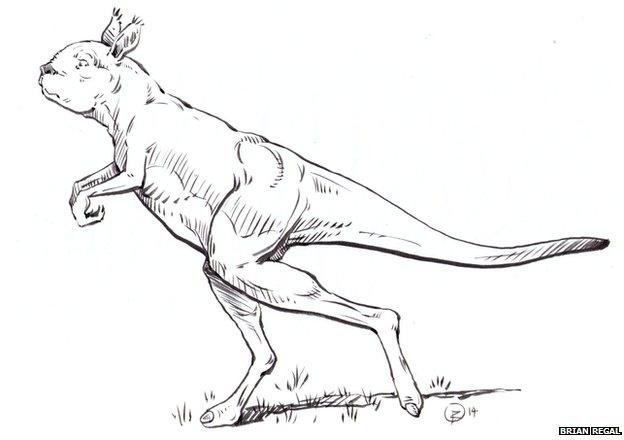

Too big to hop? Analysis of their bones suggests that the extinct roos walked on their hind legs

They roamed Australia while mammoths and Neanderthals lived in Europe - and it now seems they did so by putting one heavy foot in front of the other.

According to new research, the extinct "sthenurine" family of giant kangaroos, up to three times larger than living roos, was able to walk on two feet.

Today's kangaroos can only hop or use all fours, but their extinct cousins' bones suggest a two-legged gait.

The biggest members of the family may not have been able to hop at all.

The study, published in the journal Plos One, external, is a detailed comparison between the size and shape of the bones found in living kangaroo species and those of the sthenurines, which died out some 30,000 years ago.

Something completely different

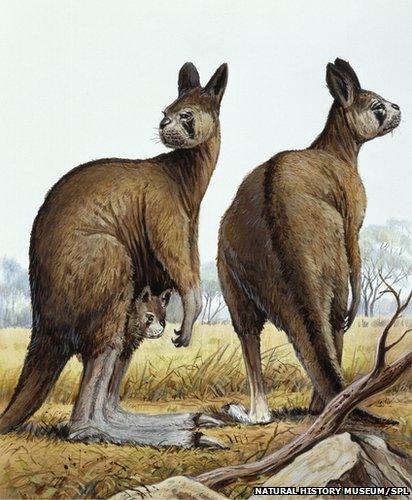

This extinct family ranged in size from quite small animals, around 1m tall, to the mighty Procoptodon goliah, which stood at a towering 2m and weighed 240kg - heavier than an adult male lion.

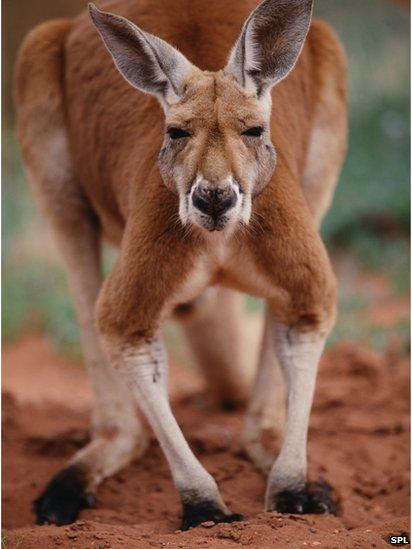

Kangaroos today walk short distances with the help of their forelimbs

Compared to today's kangaroos they were extremely stocky, with a much shorter snout and only one toe on their hind feet rather than four. Instead of grazing, they used specialised arms to browse for food in trees and shrubs.

"We've known for a while that sthenurines were different in their dietary behaviour," said lead author Prof Christine Janis, a palaeontologist at Brown University in the US.

"But the idea that they might have used a different kind of locomotion has not been thought about."

The idea of a walking giant roo first dawned on Prof Janis 10 years ago, when she was looking at their bones in a Sydney museum.

"Bones are great. Bones are really informative!" she told BBC News.

"I thought: Wait a minute, this doesn't look right. These things were weird."

Other researchers had already proposed that the giant beasts would have found it very difficult, if not impossible to walk on all fours, because of their short, stiff spines and their slender arms with long fingers for grabbing foliage.

"And that's the gait that kangaroos use most of the time. They have what's called a pentapedal gait, where the tail is used as a fifth limb," Prof Janis explained. Hopping is only used to cover larger distances, faster.

There are reports of tree kangaroos, which also browse for food with their arms, walking bipedally

So in the absence of the usual option for slow movement, Prof Janis thought, would this big family of kangaroos really hop absolutely everywhere?

"That's what I always find intriguing about fossils. Can you shoehorn them into some kind of living paradigm, or are they doing something different?"

After many more visits to Australian museums, where she made up to 101 different measurements on the skeletons of 78 extinct kangaroo specimens, as well as 66 present-day examples, Prof Janis found that the vanished marsupials did, indeed, appear to be doing something completely different.

Out on a limb

The sthenurines' long bones tended to be heavier and stronger than the relatively slender ones seen in big, hopping modern kangaroos. Furthermore, they had specific features well-suited to walking rather than hopping.

The biggest member of the family, Procoptodon goliah, weighed 250kg and stood 2m tall (up to 3m when reaching for food)

These included large hip bones that were oriented to support an upright body, and flared to accommodate big gluteal muscles, suggesting the ancient roos could support their weight on one leg.

"They had anatomy that is consistent with the hypothesis of bipedal walking," Prof Janis said.

"Now, why would they start to do that?"

She and her colleagues argue that the early sthenurines, which were smaller, probably started walking short, slow distances on their hind legs as an alternative to using all fours.

Then, as they evolved to become bigger and stockier, they may have become distance walkers and lost the ability to hop.

"The biggest ones got to a size that does strain the credulity of hopping," Prof Janis said - although she emphasised it is difficult to prove that the big beasts didn't make equally big bounds.

"Obviously you're going out on a limb when you're proposing something about an extinct animal. But all the data fit."

She said her argument was not an unreasonable stretch, given that some tree kangaroos found in Papua New Guinea have been reported to walk on their hind legs.

Unlike today's kangaroos, the sthenurine giant roos had just one toe on their hind feet

Dr Vera Weisbecker, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Queensland in Australia, said she found the study very convincing.

"The idea has been around that sthenurines may have just been too large to hop, particularly those really large forms," she told the BBC.

The explanation that they walked on two feet, Dr Weisbecker said, "may just not have ever entered people's heads".

"It's a very unusual thing to propose. And they're making a very good case."

Another marsupial expert, Dr Natalie Warburton from Murdoch University in Perth, also said the finding was unexpected.

She said the adjustments found in the sthenurines' skeletons definitely suggested a different style of getting around, but added that "precisely what that style of locomotion was is probably still going to be debated".

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published19 August 2011

- Published27 July 2010

- Published8 October 2013